- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Australian History

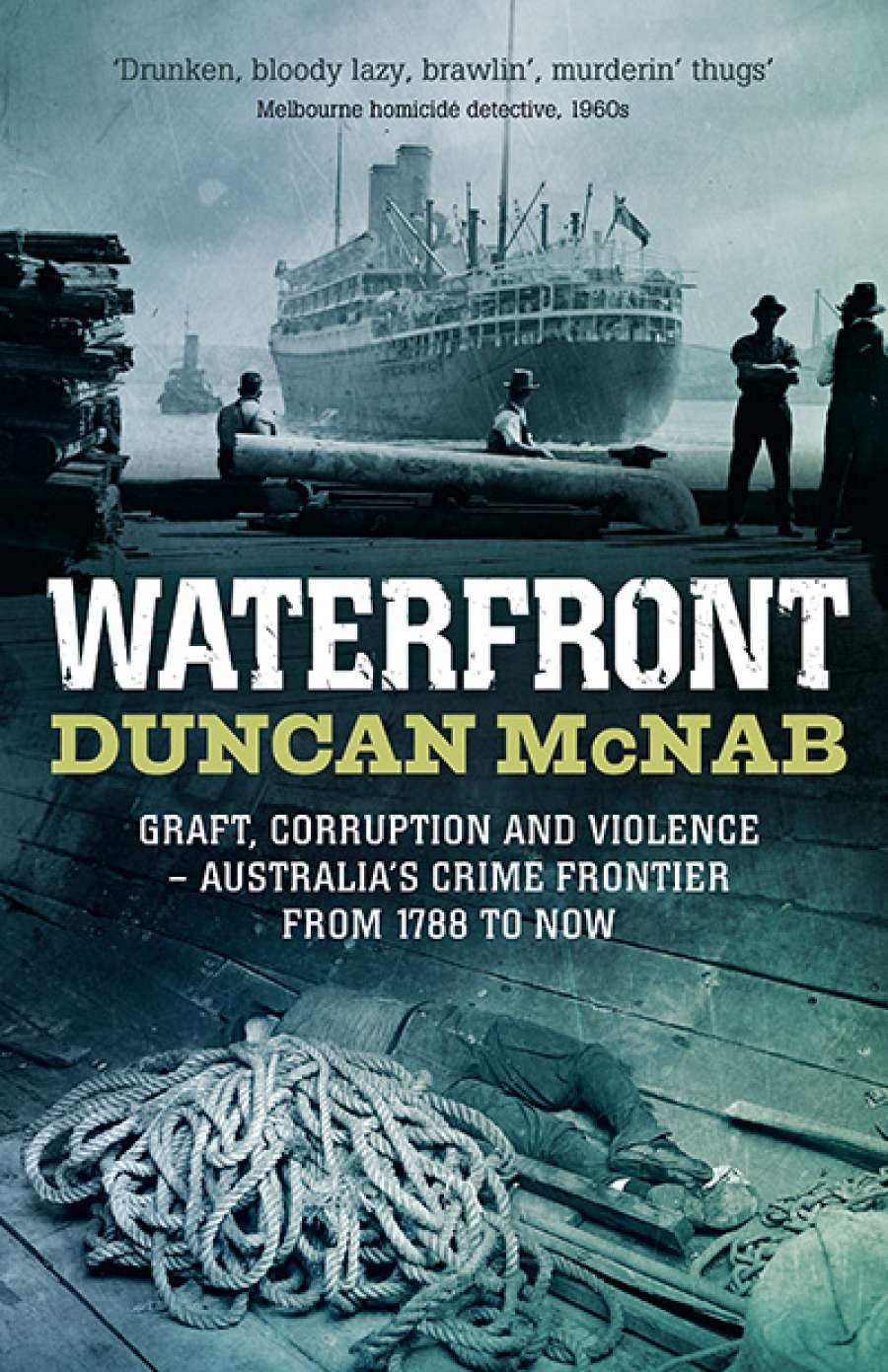

- Custom Article Title: Simon Caterson reviews 'Waterfront: Graft, Corruption and Violence: Australia's crime frontier from 1788 to now' by Duncan McNab

- Book 1 Title: Waterfront: Graft, Corruption and Violence

- Book 1 Subtitle: Australia’s Crime Frontier From 1788 to Now

- Book 1 Biblio: Hachette $32.99 pb, 352 pp, 9780733632518

Australia, an island continent whose economy is inseparable from international trade, depends on its ports to an extent that makes them vulnerable to exploitation by those who exercise control over them. Ever since the arrival of the First Fleet, McNab argues, the waterfront has occasioned theft on an epic scale, as well as murder, extortion, corruption, even treason.

A former detective in the New South Wales police force and author of several true crime books, McNab begins his brisk narrative with convict settlement. Pillaging of the scarce and valuable stores quickly developed into a thriving black market involving the military as well as civilians. Rum was particularly prized; it fuelled, as it were, the coup d'état that deposed Governor William Bligh in 1808. At the core of the dispute was a struggle for power over imported spirits, a monopoly that the imperial authorities in London ordered Bligh to end. A similar monopoly operated in relation to the export of wool, an industry dominated by John Macarthur, who was an enemy of Bligh.

Though the rum and wool cartels were broken up, the idea that control over the waterfront was a source of power would later lead to conflicts both political and criminal. The movement to organise labour in Australia first gained traction among poorly treated waterside workers, whose employment was hazardous prior to the invention of shipping containers, and precarious in economic terms.

Influential political figures such as Billy Hughes rose to national prominence through an association with unions formed among workers at the docks. Hughes (who had never actually worked as a wharfie) was still an elected waterfront union president when he became prime minister in 1915.

Waterfront unions flourished in Australia during most of the twentieth century. Such was their confidence that they tried to influence foreign affairs. During World War II, more than a century after the Rum Rebellion, communist waterfront union leaders actively supported the USSR following the non-aggression pact between Stalin and Hitler – until the Nazis reneged on the deal by invading Russia.

In addition to the physical dangers of removing goods from ships' holds, waterside workers in the early days were exposed to the threat of disease as part of their job. In the nineteenth century, a serious outbreak of bubonic plague occurred on the Sydney wharves; in the early twentieth century, an influenza epidemic similarly originated at the docks.

'The arrest of Bligh', a propaganda cartoon designed to depict William Bligh as a coward during the Rum Rebellion of 1808 (image courtesy of the State Library of New South Wales)

'The arrest of Bligh', a propaganda cartoon designed to depict William Bligh as a coward during the Rum Rebellion of 1808 (image courtesy of the State Library of New South Wales)

While now we might view plague and revolutionary ideology as historical phenomena, one aspect of the waterfront that has not changed, apparently, is its symbiotic relationship with organised crime. Some of the most notorious figures in the annals of modern Australian crime have been wharfies. In Sydney, prominent criminal identities such as Lennie McPherson and Stan 'The Man' Smith established themselves through dockside connections, while, in Melbourne, Billy 'The Texan' Longley, Graham 'The Munster' Kinniburgh, and the infamous Moran clan took a similar path. McNab quotes a senior police officer in Victoria as claiming that ninety per cent of the state's leading criminals are associated with the waterfront.

While there have been a remarkable number of royal commissions charged with investigating criminal activity on the waterfront, McNab believes that on the whole governments have shown little appetite for serious remedial action. In the early 1990s, however, the Hawke government took a bold step towards meaningful waterfront reform by using legislative means to deregister the Federated Ship Painters and Dockers Union following explosive revelations at the Costigan royal commission.

In recent decades, the rapid growth in international air travel has provided a useful new supply line for drug importers. 'Around seven million twenty-foot shipping containers pass through the docks every year – with 102,288 inspected and 14,788 examined,' writes McNab, illustrating what he sees as an insufficient effort by successive governments of both major political parties to prevent illegal importation.

According to McNab, waterfront crime today reflects Australia's past, with a diverse range of criminals including 'outlaw bikers, Southeast Asia and Middle East influenced gangs and the recruits they're targeting in the Sudanese and Somali communities'. While acknowledging the sometimes spectacular successes of law enforcement agencies and proactive legislators, McNab quotes recent statements by policing authorities, who claim that organised crime remains endemic on the Australian waterfront.

For its part, Waterfront is an engaging account of a dark aspect of Australian history.

Comments powered by CComment