- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Science and Technology

- Custom Article Title: Paul Morgan reviews 'Dancing in My Dreams' by Kerry Highley

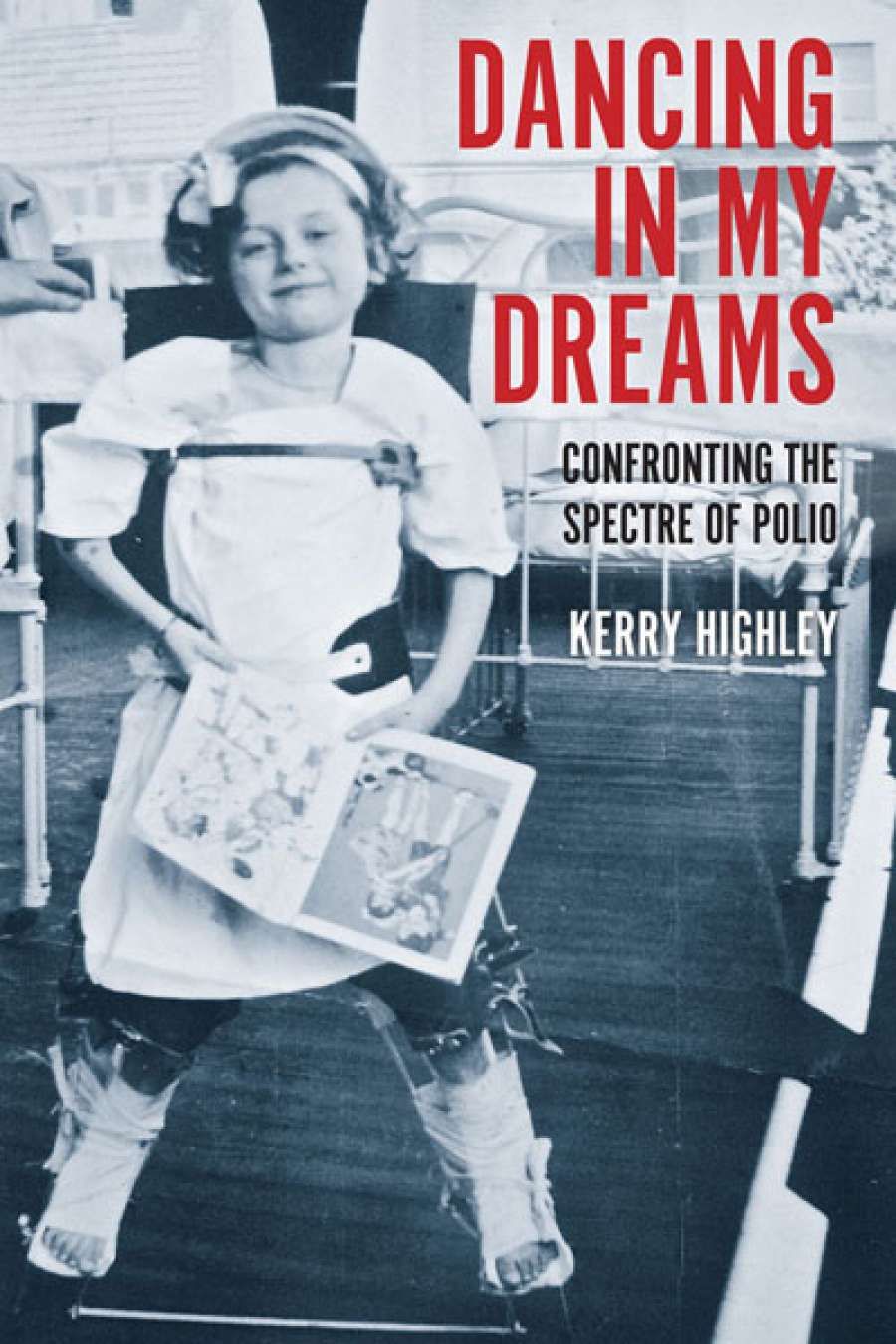

- Book 1 Title: Dancing in My Dreams

- Book 1 Subtitle: Confronting the Spectre of Polio

- Book 1 Biblio: Monash University Publishing, $39.95 pb, 262 pp, 9781922235848

This is the subject of Kerry Highley's Dancing in My Dreams, a deft and moving account of the challenges faced by the victims, health authorities, and scientists racing to understand the virus and how to tackle it. Highley gives a valuable reminder of the public health environment in which the early epidemics occurred. During the nineteenth century, three-quarters of those who practised medicine in Victoria were homeopaths, chiropractors, and quacks. By the time of World War I, science-based medicine was well established, with visible improvements in health. Uncertainty continued to flourish about polio, however. It was said to be caused by electricity, by sex with uncircumcised men, by ice cream, or even excessive tickling. As in The Plague, Australians reacted in a variety of ways: hysteria, blame, irrational beliefs, cruelty, and some – like Dr Rieux in the novel – with compassion, dignity, and respect. The Aids epidemic met with similar responses in the 1980s.

Failure to prevent polio epidemics was deeply frustrating for the medical establishment. Disease was often associated with poverty, personal weakness, and immorality. Paradoxically, polio cases did not correlate with poor housing or hygiene, low education, or even 'poor morals'. A further spur to improve treatment was economic. Orthodox treatment was focused on reducing 'needless deformity' to minimise expenditure on disability pensions. Hospitals must not become 'cripple factories', wrote prominent specialist, Dr Jean Macnamara.

When Elizabeth Kenny, a Queensland nurse, began to advocate a different approach – gentle massage and hot compresses – the medical establishment was outraged. How could a mere nurse know better than them? A Royal Commission found that her treatments were ineffective. The evidence, however, consisted chiefly of 'expert opinions'. Moreover, the evidence for orthodox treatment was no more compelling. It seems extraordinary now that randomised control trials were not conducted before dogmatic conclusions were drawn, but this appears to have been the case. Kenny's approach won support, however, especially in the United States, where she became a national hero. Without evidence, we cannot know the exact rights and wrongs of this debate. What can be stated is that Kenny nurses routinely showed more warmth and sympathy to patients, their treatment involved far less pain and discomfort, and they encouraged people to help themselves. Eventually, these principles were integrated into orthodox treatment, but still the epidemics returned. It was the long game of the researchers which eventually triumphed with a vaccine, but it was a task that took decades.

Sister Kenny and Kenny nurses at Hampton Convalescent Hospital, Victoria, 1938 (State Library of Victoria)

Sister Kenny and Kenny nurses at Hampton Convalescent Hospital, Victoria, 1938 (State Library of Victoria)

The polio virus is the essence of a living organism: a single strand of genetic material. Over a thousand million would fit into a cubic centimetre. Work in Macfarlane Burnet's laboratory in Melbourne and at centres in the United States eventually established that transmission was by ingestion of minute faecal particles, as might easily happen in a swimming pool. A shocking discovery was the ratio of those who developed symptoms to carriers. For the 5,000 or so diagnosed in the 1951 epidemic, nearly half a million Australians were actually infected in a population of eight million. After much trial and error, two effective vaccines were developed in the 1950s, by Jonas Salk and Albert Sabin, and these were rapidly taken up around the world. (The errors, it should be said, included Salk using handicapped children in an institution as guinea pigs.)

Highley tells a complex story well, drawing many threads into a rich, coherent narrative. Polio has been eliminated in much of the world but remains endemic in areas of Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. A challenge in these regions is the belief that vaccination is an American plot to kill Muslim children. Medical teams have been murdered in Pakistan by the Taliban, leading to suspension of the program there. The irrational denial of the benefits of immunisation is not limited to remote tribal areas, unfortunately. Opposition to vaccination in general is growing in Australia, with rates dropping in some of the most affluent suburbs in the country. Who would have guessed during the era of great epidemics that human irrationality would turn out to be a willing accomplice to disease and death? We are a strange species indeed.

Comments powered by CComment