- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Essay Collection

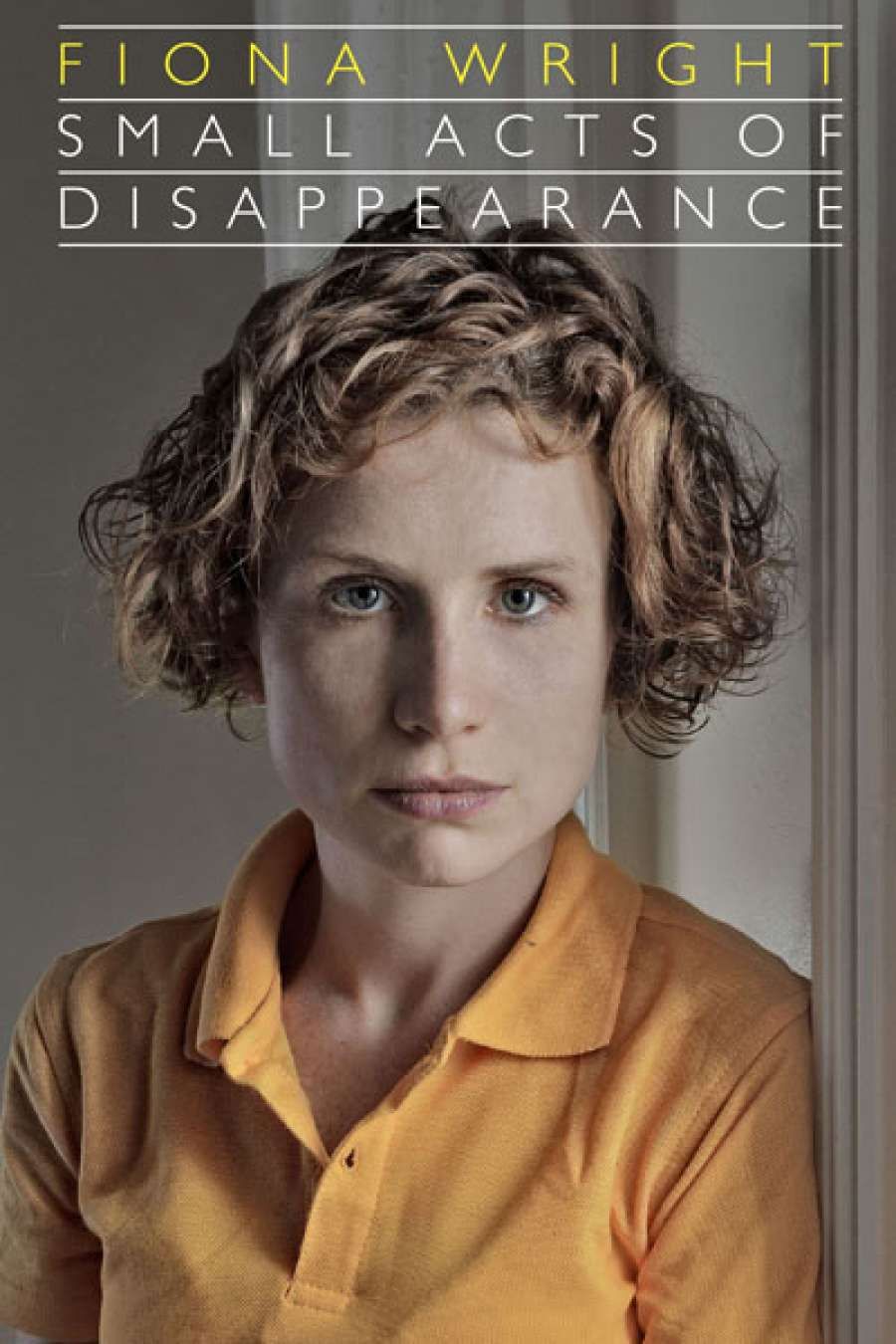

- Custom Article Title: Emily Laidlaw reviews 'Small Acts of Disappearance' by Fiona Wright

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Book 1 Title: Small Acts of Disappearance

- Book 1 Subtitle: Essays on Hunger

- Book 1 Biblio: Giramondo, $24.95 pb, 200 pp, 9781922146939

Instead of adopting the traditional 'on' preposition for essay titles, Wright titles her essays 'in' (e.g., 'In Hospital'; 'In Miniature'; 'In Passing'). This idea of being stuck 'within' something is conveyed in Gwen Harwood's poem 'Past and Present', which opens the collection: 'I speak of those years when I lived walled alive in myself.'

Wright, now in her thirties, developed anorexia as a teenager. Each essay gives us a glimpse into a particular stage of Wright's life, and how hunger or the escape from hunger, moulded it: from Wright's stint as a journalist in poverty-riddled Colombo, where she was better able to conceal her illness, to her travels around Germany and student days in affluent Sydney, where her decision to avoid food was considered 'wasteful and distasteful'.

In Illness as Metaphor (1978), Susan Sontag rails against the use of military metaphors to describe illness, in particular those which depict the body at war with itself. Sontag, who was diagnosed with breast cancer, believes such metaphors cause feelings of destruction in the minds of patients. Wright is also suspicious of metaphors, but her doubts are about the way metaphors imply, sometimes falsely, an easy solution to any problem.

Wright lists, with disdain, the wellness metaphors repeated to her in the clinic: 'It's ripping off a band-aid'; 'Living with a broken leg'; 'A CD jammed on a track'. A psychiatrist she sees 'loves poetry, thinks metaphor might cure us all'. Even Wright catches herself, at times, drawing a neat circle around her condition: 'It's just so tempting ... to try to make sense, to give a shape to my disease, proscribe (even prescribe) a meaning.' Overall, she remains suspicious of hollow diagnoses. She writes: 'This is the metaphor: in the hospital, we were told that our bodies were like cars, we have to fill them up with petrol or they stop running. I said I was trying out solar power, and was sent from the room like a naughty child.'

'This is a remarkably self-aware statement, one that encapsulates the fierce intelligence of her linked essays'

Despite a suspicion of language, Wright seeks solace in books. Shortly after her first hospital admission, Wright devours medical texts and cultural histories of hunger. Avoiding what she views as clichéd 'sick lit' and celebrity-penned 'anorexic memoirs', she chooses her preferred dose of bibliotherapy. She finds comfort in the words of fellow writers and sufferers Louise Glück and Jennifer Egan, and identifies an inner strength in anorexic characters like Rose Pickles in Cloudstreet (1991) and Teresa in For Love Alone (1945).

Unfortunately for the self-aware Wright, the qualities which make her a good writer – a keen interest in other patient's stories, a strong attention to detail – are also what's said to make her a bad patient to treat. Doctors tell her to stop over-analysing her situation, to 'stop narrating'.

Fiona Wright

Fiona Wright

In lesser hands, a reliance on the narrative logic of illness over its lived reality could distance the reader. However, it should be noted that Wright's book is subtitled 'Essays on Hunger', not 'A Memoir of Hunger'. This formal distinction is important, and her focus on the political nature of the body, and how this is gendered, is every bit as involving as the many confessional moments dotted throughout her essays. Wright also takes her authorial role seriously; she sees the harm in turning her fellow patients into 'kooky characters' to add colour to her story, and she successfully avoids committing what she considers a narrative violence against them.

Wright concedes that there are times when she struggles to make herself present in her prose, noting how a writing group once described her poetry as 'strangely disembodied'. No such claims can be made about Small Acts of Disappearance. Despite her earlier reservations about metaphors, Wright locates the emotional pain caused by her anorexia, viscerally, in the image of the stomach. 'The stomach,' she writes, 'contains more nerves than the spinal cord ... it can feel and agitate with all the emotions we usually ascribe to the heart.'

To soften such heartbreak, Wright turns words into a weapon she can use to fight her illness: 'I sometimes think this is all I am doing, trying to use words to cut my way out of the trap. They're not enough, but they are the strongest steel I have.' Wright's steel is also her sharp poetic voice. Small Acts of Disappearance establishes her as a bold new voice in Australian non-fiction.

Comments powered by CComment