- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Gay Studies

- Custom Article Title: Sylvia Martin reviews 'Unnamed Desires' by Rebecca Jennings

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

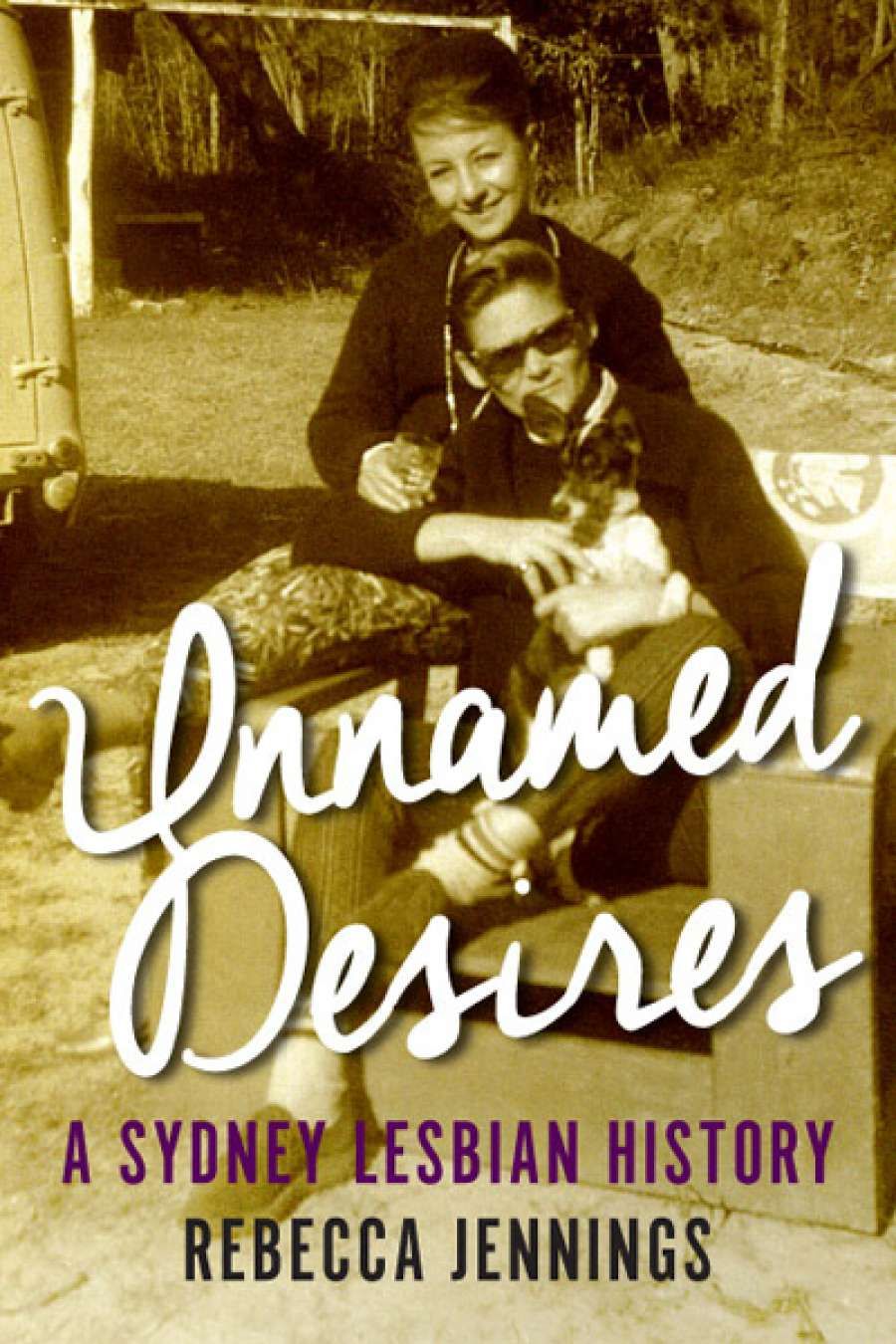

- Book 1 Title: Unnamed Desires

- Book 1 Subtitle: A Sydney Lesbian History

- Book 1 Biblio: Monash University Publishing, $34.95 pb, 149 pp, 9781922235701

As late as 1972, a lesbian writer in the magazine Camp Ink argued that 'there has developed a conspiracy of silence and lies with regard to Lesbians. The church calls her a sinner, the law makes her a criminal, and psychiatry tells her she is sick.' Unlike male homo-sexuality, lesbianism has never been illegal, but that does not mean that women have not experienced the force of the law because of their sexuality. In the 1950s Willson's flat, where she lived with another young woman, was raided; she, being older, was portrayed as the seducer and sentenced to detention at the Girls Training School in Parramatta. Interviewees also gave accounts of bizarre incidents such as police telling them they would be apprehended if they weren't wearing at least three items of women's clothing.

Medical discourse has also proved punitive for lesbians: from shock treatment and aversion therapy to turn them into 'normal girls', to the case of a woman who had her teaching scholarship at Macquarie University withdrawn in the early 1970s after she wrote a lesbian poem in the student newspaper and was declared 'medically unfit' by a psychiatrist.

While a bar subculture thrived among gay men, hotels were a masculine culture that implicitly and even literally in some periods excluded women. Some lesbians attended gay bars in the 'camp' postwar Sydney scene, but they tended to organise themselves socially in more private networks such as house parties. Later, women's clubs like Clover were formed, and lesbian nightclubs like Ruby Reds (Ruby's) opened in the early 1970s.

'She offers a nuanced understanding of Sydney's lesbian history ... that remains alert to the interconnections between gender and sexuality in shaping lesbian experience'

The boundary between women's friendships and lesbian sexuality has been more permeable than the male equivalent (although many would ascribe a homoerotic dimension to mateship). In the 1930s it was still possible for women who would not describe themselves as lesbians to live in so-called romantic friendships as companions, and even today such relationships exist. Many women hid their relationships, living as single friends and keeping a bed made up in a spare room when family visited. (I knew of a couple in the 1990s that would not put their double sheets on the clothesline.) The secrecy surrounding lesbianism often made it difficult for women to meet others, and Willson commented on the fear she would be taken for a 'sex maniac' if she approached a woman, reflecting the sexological discourse of lesbians as oversexed women. On the other hand, some of the interviewees enjoyed the feeling that they belonged to a secret society. It goes without saying that both emotions could exist simultaneously, offering a frisson of sexual excitement.

Rebecca Jennings

Rebecca Jennings

Gay Liberation and Women's Liberation offered new opportunites for lesbians in the 1970s, but 'coming out' brought its own difficulties, from fear of exposure to negative reactions and retribution. Although feminist politics appealed to lesbians and they were a strong presence in Women's Lib, splits emerged as heterosexual feminists either feared being accused of being lesbians or that their projects would not get funding. Consequently, lesbians were often ostracised or expected to keep quiet about their sexuality. A large lesbian separatist movement emerged during this period; it was common to be asked if you were a separatist or a coalitionist, terms that have little meaning today.

While the situation has improved for lesbians and gays in the twenty-first century, Unnamed Desires is a timely volume, examining as it does the radical changes that have taken place in the narratives surrounding women's same-sex desire and relationships over the course of just a few decades. In 2015 the dominant narrative is a paradoxically conservative one where sexuality is assumed to be innate and the sexual fluidity of the 'queer' 1990s is eschewed in order to bring about 'marriage equality' with the legalisation of same-sex marriage. With a plebiscite on the subject proposed for 2016, many of the stereotypical discourses of the twentieth century are already being aired again by those opposing it.

Comments powered by CComment