- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Custom Article Title: Fiona Gruber reviews 'Banksia Lady' by Carolyn Landon

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Book 1 Title: Banksia Lady

- Book 1 Biblio: Monash University Publishing, $39.95 pb, 261 pp, 9781922235800

In Banksia Lady, biographer Carolyn Landon explores both the life of the largely self-taught Rosser and the fascinating history of botanical collecting and illustrating in Europe and Australia. The project started at Monash University in 1974, where Rosser was employed as the science faculty artist and at a time when the young institution – its first student intake was in 1961 – was flush with ambition and cash. By the time the project finished twenty-six years later, such a grandiose and esoteric endeavour would have been unthinkable. Even at the time, it was a curiously old-fashioned project for a young thrusting university; the heyday of florilegia was in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

Banksias take their name from the botanist Joseph Banks, who joined James Cook on his world voyage between 1768 and 1771. Thousands of botanical samples were collected on this momentous voyage, but even so, on his return to England Banks failed in his attempts to publish a florilegium of his and fellow botanist Daniel Solander’s discoveries; the copperplate engravings he commissioned, based on drawings and watercolours by Sydney Parkinson (who had died on the voyage home) were eventually published at great expense between 1980 and 1990 in thirty-four parts. As Landon recounts, they had been a whisker away from being melted down for bullets during World War II.

The more modest but still large three-volume set of The Banksias cost Monash a vast amount too and was published by three separate publishers between 1981 and 2000. It contains seventy-six full-sized colour plates, is handsomely bound in green leather and buckram, and all three will set you back almost $10,000. Its fame stretches far beyond its bindings; thousands have seen the meticulous watercolours that it contains, in publications, prints for sale, and exhibitions across Australia and the world – Rosser’s banksias were the first non-English art to be exhibited at the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew.

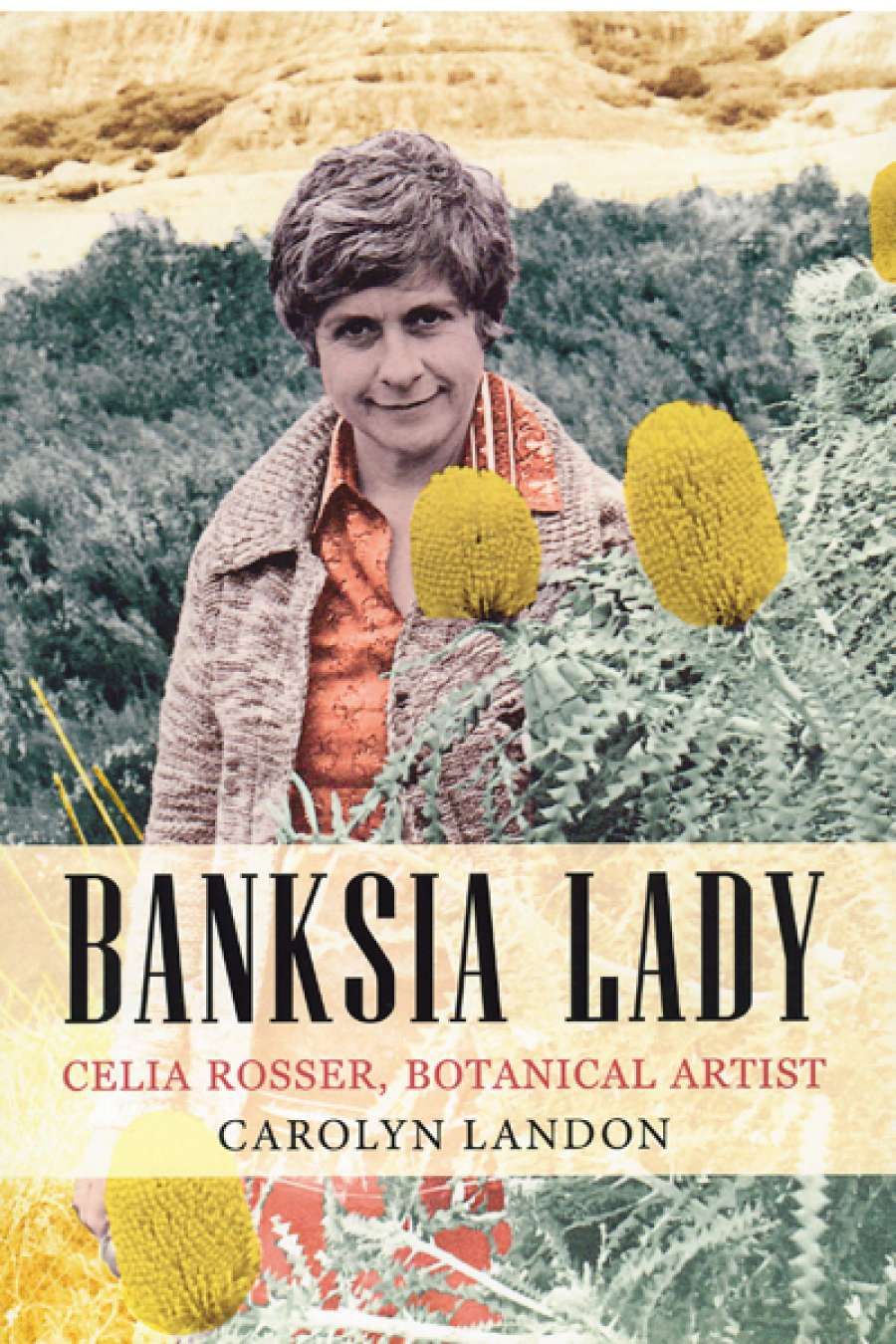

Celia Rosser poses with the first volume of The Banksias, 1982 (photograph by Sarah Walshe via Wikimedia Commons)

Celia Rosser poses with the first volume of The Banksias, 1982 (photograph by Sarah Walshe via Wikimedia Commons)

Alongside honorary degrees and an OAM, Rosser was awarded the Linnaean Society of London’s Jill Smythies Award for botanical illustration. It is a remarkable achievement for a woman who left school at fourteen, trained as a fashion illustrator, and who had to fight for painting time while bringing up a family.

By the time Rosser joined Monash in 1970, aged forty, she had acquired a modicum of fame; an exhibition of flower paintings had been praised by The Age’s influential art critic Bernard Smith, who compared her work to the great botanical artists Pierre-Joseph Redouté and the Bauer brothers. She had also illustrated a pocket guide to the wildflowers of Victoria and had been commissioned by the Maud Gibson Trust to paint the six Victorian banksias, paintings which would be housed in the herbarium, the scientific heart of the Botanic Gardens in Melbourne. In becoming involved with the Botanic Gardens, Rosser was following in a tradition started by its first director, Baron Ferdinand von Mueller, who employed a band of women artists and correspondents. One of the prejudices that Rosser and other female botanical artists have had to contend with has been the idea that the scientifically accurate and highly detailed work they undertake is nothing more than flower painting, and a perfect hobby for the artistically inclined ‘lady’. The education of Celia Rosser is one of the main themes of this biography; Landon burns with indignation on her subject’s behalf when it comes to the patronising machinations of faculty members and Rosser’s own husband.

‘The Banksias, which combines Rosser’s illustrations with botanist Alex George’s text, is one of the greatest botanical publishing achievements of the twentieth century’

Alongside this is the strong friendship that Rosser developed with Monash botanist George Scott and the eminent English writer William Stearn; both were hugely and benignly influential in teaching her how plants worked and her place as an artist in an ancient tradition of accurate botanical illustration that stretches back to Egyptian tomb paintings. She became aware, too, of how important her work was in the context of a continent that had been the site of some of the greatest botanical discoveries.

Rosser, now in her eighties, lives in a house near Wilsons Promontory with a front door made of banksia wood. Her gallery, where many of her paintings can be seen, is next door. Visitors, if fortunate, can hear firsthand the artist’s tales of decades of travel in search of every banksia in its place of first recording.

Landon’s biography captures both the spirit of the woman and the momentousness of her artistic achievement.

Comments powered by CComment