- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Letters

- Custom Article Title: Patrick McCaughey reviews 'My Dear BB' edited by Robert Cumming

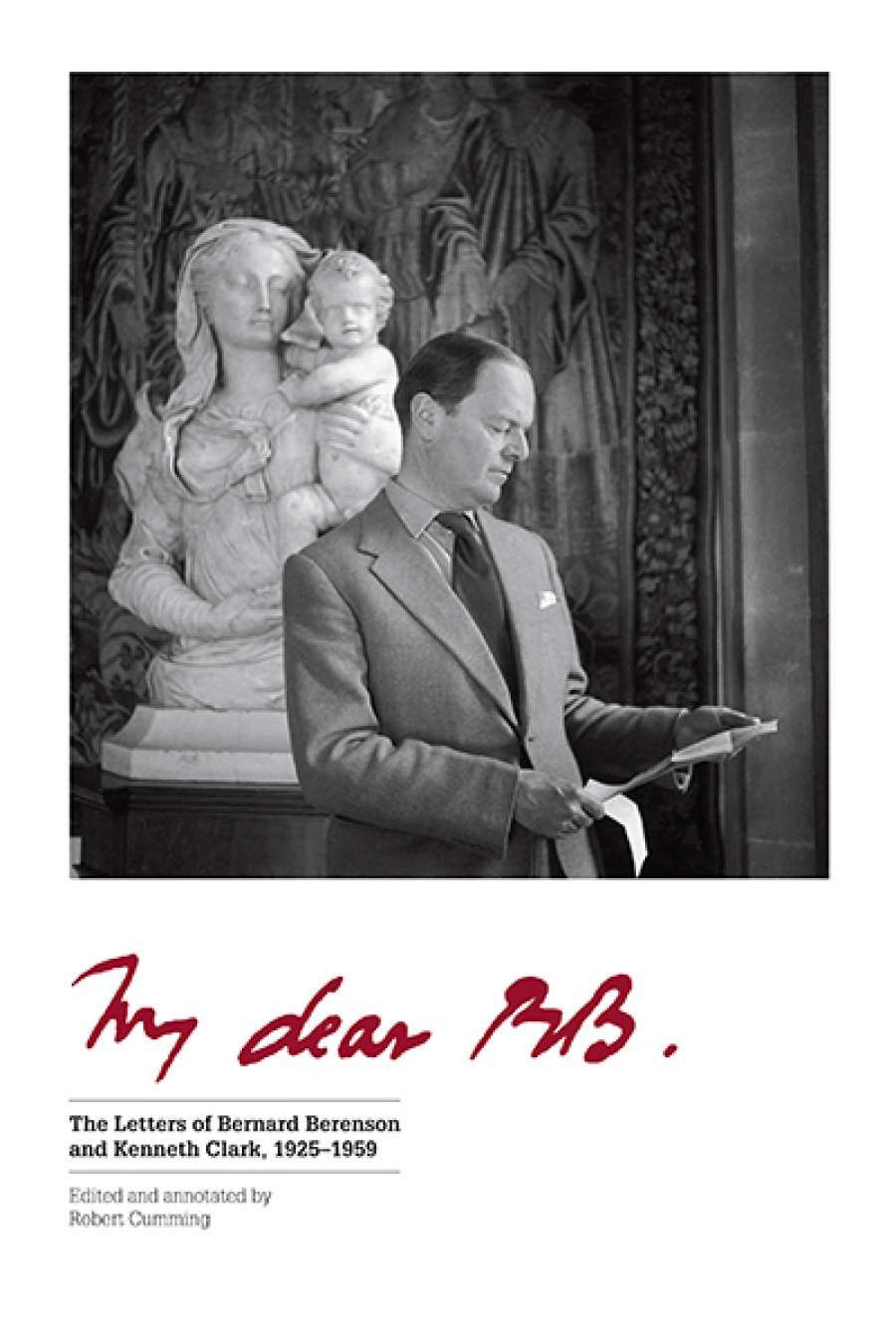

- Book 1 Title: My Dear BB

- Book 1 Subtitle: The Letters of Bernard Berenson and Kenneth Clark, 1925–1959

- Book 1 Biblio: Yale University Press (Footprint), $69 hb, 598 pp, 9780300207378

Clark was summarily dismissed from the Florentine Drawings project in May 1929. The Court regarded him as both insufficiently devoted to the Master and to the minutiae in compiling and revising the lists of drawings – ‘those terrible lists’, as Clark called them in an unguarded moment. It must have come as a relief. The twenty-six-year-old Clark had already published The Gothic Revival (1928) and was presently cataloguing the Leonardo drawings in the Royal Library at Windsor, his first major contribution to scholarship. By 1931 he had succeeded his old mentor, Charles Bell, as Keeper of the Fine Art Collection at the Ashmolean. He modernised and expanded the museum, lending Oxford the money, interest free, to pay for the expansion. Two years later at the age of thirty, Clark became Director of the National Gallery and thus began what he himself called ‘the Great Clark Boom’.

One of the underlying rhythms to this correspondence is the changing status of BB and Kenneth Clark. Berenson turned seventy in 1935 and stood at the height of his prestige. He had survived the great Depression. The odd butler and gardener had been let go, but he had been more than compensated by Joseph Duveen, the notorious dealer, who placed him on a handsome annual retainer after years of paying him, irregularly, commissions on sales and the authentication of works. Added to his wealth and social standing – crowned heads of Europe joined the cavalcade to I Tatti – his favourite and most gifted pupil was director of one of Europe’s greatest picture galleries. Their correspondence regarding acquisitions and attribution is brisk and interesting.

By the end of the 1930s subtler but pervasive changes came over the relationship. In 1929 Clark heard Aby Warburg lecture at the Bibliothek Hertziana in Rome. For Clark, he was ‘without doubt the most original thinker on art history of our time’, declaring that after hearing the lecture ‘my interest in “connoisseurship” became no more than a kind of habit’. Parts of Clark’s best book, The Nude (1956), carry elements of Warburg’s ideas about the migration and descent of images from antiquity. For Berenson, Warburg and his followers were the enemy; he even denounced Erwin Panofsky, the most gifted of the Warburgians as a ‘Goebbels’, which is shocking given Berenson’s origins in the Pale of Settlement. He told Clark ‘truly German Jews do make a Nazi out of me’. After the war, he kept at it, speaking of ‘German Jews who run all art matters in all Western lands’. With regard to Warburg, Clark took G.M. Hopkins’s advice: ‘Admire and do otherwise.’ But he was not tone deaf to modern German art history. He reviewed Richard Krautheimer’s subtle and compendious monograph on Lorenzo Ghiberti favourably in the Burlington Magazine and teased Edgar Wind over his intellectual gyrations in Pagan Mysteries in the Renaissance.

Walking in the hills above I Tatti, March 1950. (The only known photograph of Clark and Berenson together. The identity of the third man and the photographer is unknown.)

Walking in the hills above I Tatti, March 1950. (The only known photograph of Clark and Berenson together. The identity of the third man and the photographer is unknown.)

‘One of the underlying rhythms to this correspondence is the changing status of BB and Kenneth Clark’

Clark’s admiration for contemporary British art represents one of his best sides. During World War II, Clark’s imagination and drive created the War Artists Scheme to provide a pictorial record of the nation at war both on the home front and on the battlefield. It resulted in such masterpieces as Stanley Spencer’s shipyard and steel works paintings, Henry Moore’s Shelter Drawings, and Graham Sutherland’s visions of bombed-out cities. For Clark, Henry Moore was primus inter pares, and he arranged for the sculptor to meet Berenson at I Tatti. The visit went well. BB wrote to Clark: ‘I took to him at sight, his candour, his naturalness, his freedom from himself. I took him to see all the bits of sculpture and he gave side-glances at the paintings. Never a more appreciative looker. I do not wonder you have taken him to your hearts.’

But Robert Cumming, the astute and assiduous editor of this correspondence, footnotes the letter with an extract from Berenson’s diary:

Henry Moore lunched here, still provincial in clothes and accent, but one of the most appreciative persons I ever took around the house. We looked at sculpture chiefly, and he dashed forward without prompting to what best deserved attending to … how account for the fact that his own sculpture is so revoltingly remote from what I feel about art? … Why does this so sensitive so honest minded man produce such horrors of distortion, misinformation and abstraction? More incomprehensible still are his ardent admirers, Kenneth Clark, for instance ...

BB early on sensed a separation from Clark. ‘If there is anything I now crave for it is your affection. You may say I have it, and far would it be from me to doubt it. I want affection with perfect confidence, perfect ease. Without timidity or holding back of any sort. What I crave for is a brotherly comradeship.’ Berenson was seventy-two when he wrote that in 1937. Clark, some weeks later, replied diffidently: ‘I come from an undemonstrative family and my feelings are as stiff as an unused limb. You must never doubt that my admiration for you is combined with great affection ... but for me our relations must always be of master to pupil.’ After the war, Clark wrote more expansively. ‘I Tatti is my home ...’ he remarked on more than one occasion. He would retreat there to write and escape from his own fraught marriage. Later, Saltwood Castle, the Clarks’ last and grandest home, did much to anneal Kenneth and Jane.

Off-puttingly, a stream of flattery and sycophancy runs through the Clarks’ correspondence with BB. That was the coin of the realm at I Tatti. It accounts for the unease, even distaste for the aura surrounding Berenson and his circle. For all the talk of Goethean humanism, there is a creepy, feline quality to BB.

‘For all the talk of Goethean humanism, there is a creepy, feline quality to BB’

None of this detracts from this superbly edited and annotated edition. Cumming’s introductions to the various chapters form a deft narrative of the two lives. In addition to his own perceptive afterword, the book contains such useful documents as Clark’s surprisingly stilted address at Berenson’s memorial, held in the Palazzo Vecchio no less, as well as Berenson’s wishes for I Tatti once it became an institution under the crimson flag of Harvard. Cumming provides vivid Brief Lives of the major dramatis personae. Yale have lumbered the book with a crashingly boring cover: Warum?

Kenneth Clark paid a fleeting visit to Australia in early 1949. As every student knows, he spotted both Sidney Nolan and Russell Drysdale, bought paintings from both of them, and supported them loyally in London. He writes to Berenson about the visit: ‘I enjoyed Australia far more than I had expected to ... the brilliant climate seems to have had a magical effect on the Anglo-Saxons, removing their inhibitions and hypocrisies. Of course they are very naive – hardly out of the pioneering stage – but they are a gifted people, only held back by laziness ... It is a country for painters and in fact they have quite good ones ...’

Comments powered by CComment