- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Society

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Quarantined!

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

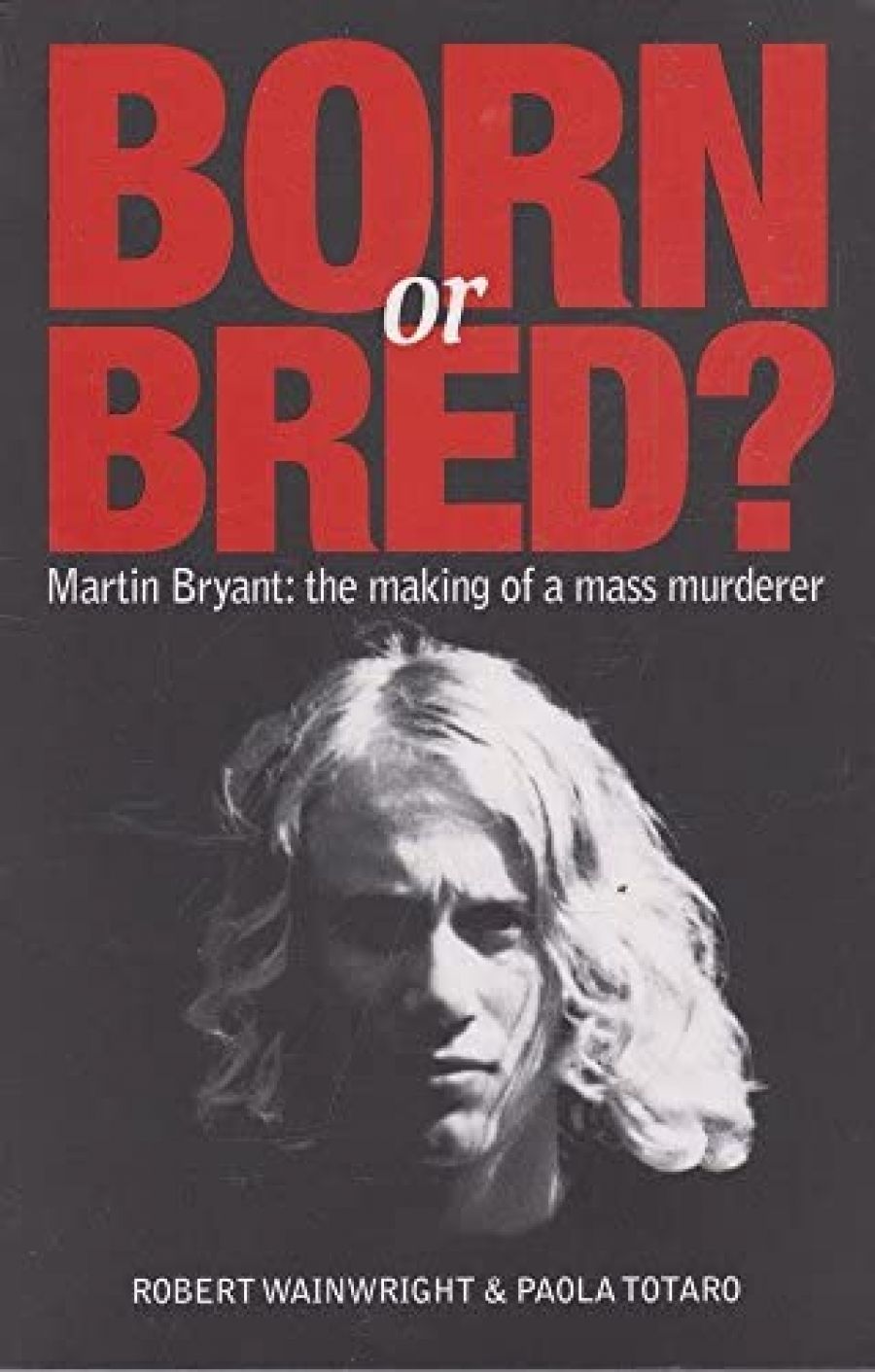

Robert Wainwright and Paola Totaro’s Born or Bred? Martin Bryant: The Making of a Mass Murderer is a tendentious and poorly written book about a fascinating topic. Riddled with clichés and full of baseless speculation, it displays neither great sensitivity nor penetrating insight. Despite the important subject matter, Wainwright and Totaro have written a shallow and dubious book.

- Book 1 Title: Born or Bred?

- Book 1 Subtitle: Martin Bryant: The making of a mass murderer

- Book 1 Biblio: Fairfax Books, $34.99 pb, 288 pp

This is a great shame, because Born or Bred? is a work of considerable investigation and research. The authors have spent several years piecing together the story of Bryant’s broken family life, with extensive cooperation from his mother, Carleen Bryant. They also spoke to Bryant’s childhood friends, his doctor, lawyer and even his former warden at Risdon Prison.

According to the news website Crikey, Carleen Bryant is reportedly suing the authors and the publisher, Fairfax Books, for breach of copyright. The dispute appears to have arisen over the extensive excerpting of the manuscript of Carleen Bryant’s memoirs in Born or Bred? The authors themselves inform us in the first chapter that Mrs Byrant had ‘withdrawn from the project’, which makes one wonder why they pressed ahead and published Mrs Bryant’s words. The issue may well be decided in court.

Legalities aside, there is an ethical dimension to the authors’ casual dismissal of Carleen Bryant’s wishes in this matter that will be instantly understandable to readers of Janet Malcolm’s The Journalist and the Murderer (1990). Indeed, Wainwright and Totaro appear to have struggled with some of the moral ambiguities that Malcolm dissects so clinically in her examination of journalist Joe McGinniss’s book Fatal Vision (1981). They argue on page nineteen that ‘this book is not what Carleen Bryant had in mind because more often than not it challenges her world view’, which may be true. But they have also relied upon Mrs Bryant’s ‘world view’ in their research. Reading Born or Bred?, it becomes clear that Wainwright and Totaro could not have written the story of Bryant’s family life and upbringing without Carleen Bryant’s extensive cooperation.

Sadly, the worst that can be said about Born or Bred? is not simply that its authors betrayed the confidence of Bryant’s mother. The book itself is disappointingly vacuous and judgemental. Despite claiming to have practised journalistic distance and to have grappled with complex issues of moral agency and guilt, Wainwright and Totaro have written this book like a Sunday newspaper feature. There is plenty of slang, innuendo and pseudo-psychology. All too often, real insight is abandoned in favour of scathing judgements in the bluntest prose. For instance, on page 146, when describing a key interview between Bryant and police after the mass murders, Wainwright and Totaro refer to Bryant thus: ‘The bastard sits back in his chair and points to himself.’

There is a reason why this kind of abusive slang generally doesn’t make it into reputable works of non-fiction. It is inaccurate and confusing. Martin Bryant is not illegitimate. If Wainwright and Totaro are using the term as an insult, the question that follows is: to what end? Insulting Australia’s most notorious mass murderer seems pointless. A couple of sentences later, Wainwright and Totaro write: ‘Bryant has fucked himself with that comment. And he knows it.’ If the authors are trying to convey that he knowingly incriminated himself, why not simply say so?

Born or Bred? is undermined by its sensationalist style. Even for readers enamoured of true crime as a genre, it is difficult to find anything to praise in Wainwright and Totaro’s prose. The book is also poorly edited: tenses change rapidly and mysteriously, while clauses break loose from their predicates. There is no index, an oversight. The narrative is broken up into overly small chapters, which jump around in time and space, seemingly with little internal logic to their organisation. Several chapters about Tasmania’s convict past are only marginally relevant. Wainwright and Totaro are incapable of writing more than a couple of paragraphs without foreshadowing Bryant’s eventual crimes.

There are some saving graces. The latter part of Born or Bred? veers unexpectedly towards an intelligent discussion of the psychiatry of violence and the problems of adolescent mental health, including some thoughtful interviews with Bryant’s psychiatrist, Paul Mullen. But this lasts for just a single chapter, before we are plunged into a fictionalised account of Bryant’s killing spree at Port Arthur. This special section has been ‘quarantined’ (to use the authors’ specious word) at the end of the book and flimsily justified on the grounds that ‘in the search to answer why Martin Bryant went on his rampage, the result and impact of his crime should not be forgotten’.

Disappointingly, Wainwright and Totaro’s reconstruction of the events of that day reads not as a sober exploration of the impact of violent crime, but as the salacious glorification of it.

Comments powered by CComment