- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Vive la bagatelle!

- Article Subtitle: A contemporary life of Marcus Clarke

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

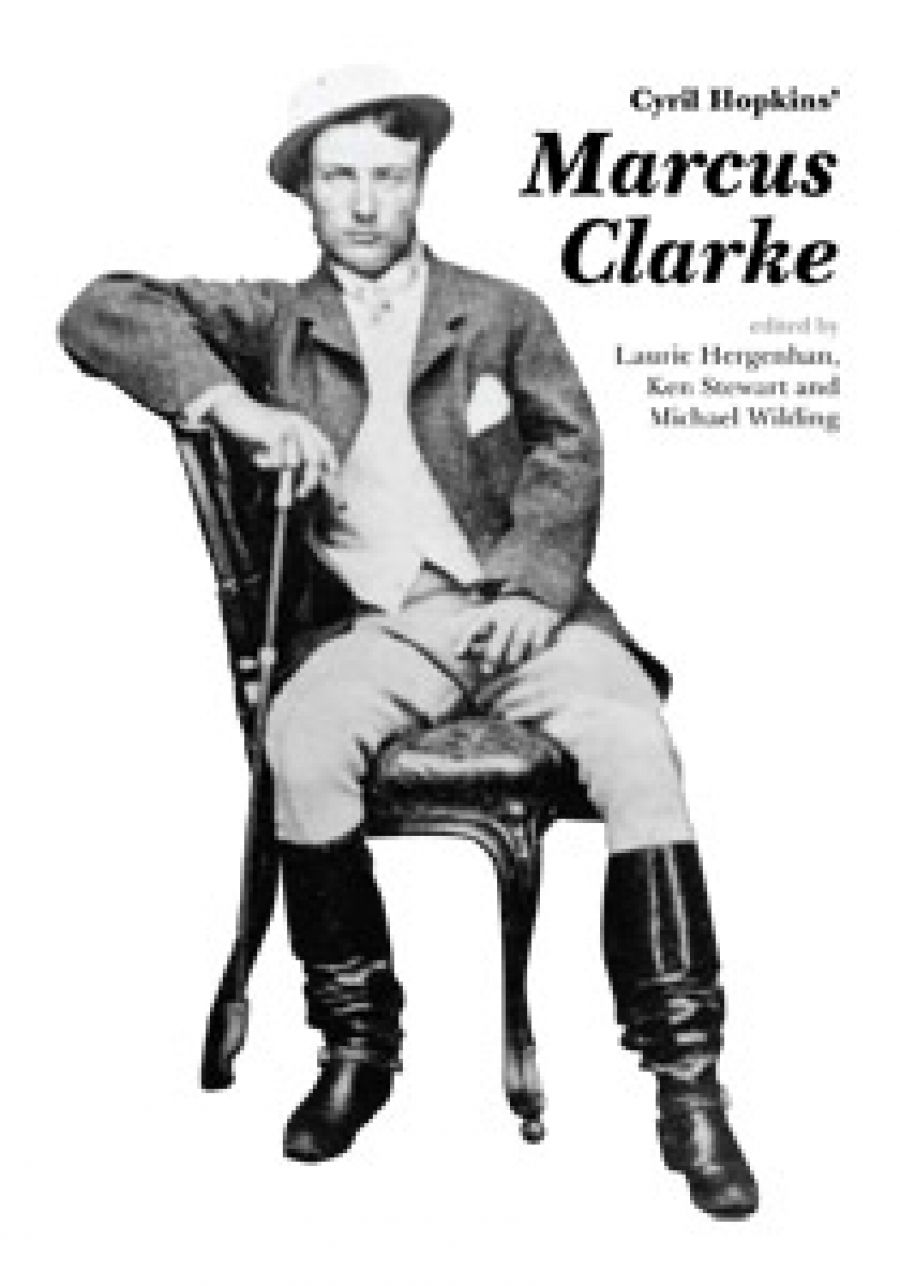

The slightly odd title of this volume – not Marcus Clarke, but Cyril Hopkins’ Marcus Clarke – is reminiscent of a spate of movies in the 1990s, including Bram Stoker’s Dracula and Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. Those weren’t the authentic products, but this book does present Hopkins’s Clarke, in that much of the volume is made up of his childhood memories of the author of For the Term of His Natural Life (1874) and long extracts from Clarke’s letters to Hopkins.

- Book 1 Title: Cyril Hopkins’ Marcus Clarke

- Book 1 Biblio: Australian Scholarly Publishing, $39.95 pb, 386 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

There is limited biographical material available on Clarke (1846–81). Shortly after his death, aged thirty-five, a few biographical pieces were published, but these notably neglected his English childhood and concentrated on his life in Australia after his emigration to Melbourne at the age of sixteen. Brian Elliott’s 1958 biography, still the only full scholarly biography, made cautious use of Hopkins’s manuscript to flesh out Clarke’s childhood and early youth. Andrew McCann’s Marcus Clarke’s Bohemia: Literature and Modernity in Colonial Melbourne (2004) is literary criticism rather than biography, although it contextualises Clarke within his milieu in colonial Melbourne and as a cosmopolitan and modern figure.

Clarke is best known for his masterly novel of the convict era. His colonial journalism and early stories are less familiar, though often anthologised. Many people would be familiar with the preface to Adam Lindsay Gordon’s poems which argued that ‘weird melancholy’ was the keynote of the Australian bush. Again, the valuable introduction offers a painstaking tracing of the roots and routes of the preface, which originated in essays accompanying Photographs of Pictures in the National Gallery, Melbourne (1873–74).

Clarke’s mother died in 1850, when he was four, and his father appears to have sunk into a depression. Clarke was critical of his father’s neglect of his upbringing. Hopkins recounts some bitter tales of early debauchery and bad company. Editorial hindsight suggests another diagnosis of Clarke Sr’s bad parenting, particularly as he died in an asylum. The introduction offers further insights, including the suggestion that the flogging scene in His Natural Life is inspired as much by Clarke’s experiences of being sadistically and regularly flogged by his headmaster at the Highgate School in London as by the convict history it depicts. Clarke’s father’s illness and the collapse of his financial expectations prompted Marcus’s emigration to Australia, where he had influential relatives who were supposed to assist him into banking or some equally respectable profession. He did indeed spend some time as a junior clerk in the Bank of Australasia. Of this career Hopkins comments,

Remembering his dislike of mathematical studies at school, I was not surprised to learn from Mr Mackinnon’s memoir that … though a universal favourite, he had received a friendly hint from the manager that he had better seek some more congenial employment, followed up by the presentation of a quarter’s salary in advance and a friendly parting word.

Clarke describes his own career (with some exaggeration) in another letter to Hopkins: ‘What a life I have had! Bank clerk, gold buyer, squatter, overlander, play writer, author and man of means! Share buyer and speculator too! Vive la bagatelle! If I had only saved the money I have made! Lord what fools these mortals be!’

One major feature of Hopkins’s volume is the transcription of private letters which, in most cases, are no longer extant. The biography shows Clarke as an intimate friend. The letters give valuable accounts of Clarke’s reading, and direct, if dramatised, responses to life in Melbourne. ‘This colony is going to the deuce as hard as an insane ministry, a reckless Assembly, an idiotic population and a triumphant banking interest can drive it,’ he comments to Hopkins at one point. Clarke is a somewhat idealised and distant figure in the biography, become larger than life through physical distance, the influence of his own self-representation and achievement, as well as his early death.

After his stint in the bank, Clarke went up-country, first near Glenorchy and later outside of Stawell, as a jackeroo, soaking up the scenery, experiencing bush life and writing to Hopkins about the drought of the 1860s, the heat and his experiences droving and fighting bushfires, all of which, as Cyril points out, he took careful note of, and later turned to fictional account. Despite fantasies of squatting and some ideas of joining the mounted police, Clarke did not enjoy outback life. Hopkins says, ‘his letters had made it sufficiently evident to me by this time that he was longing in his heart for some more congenial occupation. He enjoyed the open air life and the riding about the country but felt that his literary gifts would have no scope in such a career.’

He was apparently no better at jackerooing than he was at clerical work. Released, he finally pursued a more lasting and congenial career as a journalist, working first for the Argus in Melbourne, then writing in various capacities for the Argus, the Australasian, the Age and the Leader, as well as various regional Victorian newspapers, interstate papers and the London Daily Telegraph. Clarke had already been writing and publishing stories, poetry and articles well before this. ‘The Puff Conclusive’, for instance, an article satirising Australia’s excessive lionising of visiting British actors, appeared in Melbourne Punch in 1863.

In 1870 he achieved a more reliable permanent income with a position at the Melbourne Public Library. There are mixed reports on the amount of effort Clarke put into being a librarian. As usual, he gives Hopkins a number of different versions of his salary. Hugh McCrae recounts the story of Clarke leaving his still-smoking cigar in the mouth of the large metal lion which then graced the steps outside the Library: ‘“The lion, smoking the cigar, became a signal to his friends that Marcus was within”.’ McCrae implies that Clarke put limited effort into the job. The chief librarian at the time commented,

If his services to the institution were not what they might have been, he at least gained the admiration and affection of his colleagues, and pardonable pride may be felt in the fact that one who was so auspiciously connected with the early literature of Australia was also closely associated with the Public Library … Genius has an imperialism of its own.

However, the editors point out that Clarke did take his job seriously, seeing his publications as a way of promoting the Library, to which he dedicated a number of his works.

Another outcome of Clarke’s return to Melbourne from the bush was his involvement in the formation of the Yorick Club, for which he provided a skull. The club, founded in 1868, was a regular hub for literary types including Adam Lindsay Gordon, Henry Kendall, Garnet Walch and George Gordon McCrae. Clarke wanted the club to be called the Golgotha club, in honour of the skull, but was overruled. Between the Yorick Club, which stayed open until four a.m., absinthe drinking at the Café de Paris and attendance at the Theatre Royal next door in Bourke Street, Clarke’s accounts of his life give some sense of the bohemian lifestyle possible in the 1860s and 1870s, a boom period in gold-rich Melbourne.

Ultimately, Clarke became jaded with this existence. As all accounts make clear, he was no money manager, and attempted to maintain a champagne (or absinthe) life on an insufficient income further reduced by speculations, loans and unsuccessful ventures in journal publications such as the short-lived Humbug. Clarke’s marriage to the actress Marian Dunn was apparently happy, but the addition of six children did not ameliorate his financial woes. As with questions about his dedication to the Library, his devotion to his literary career has been queried, particularly along lines which would be familiar to modern novelists: where was the next great novel after his masterpiece? As Hopkins charmingly puts it, ‘those who live by their pen must devote much of their time to the drudgery of literature’, by which he apparently means that Clarke had to spend much time in routine journalism in order to pay the bills.

Hopkins’s biography suggests, vaguely, that Clarke died of debt and disappointment, but his account deals with the life, not the death (the editors don’t really expand upon this), so the biography seems unfinished.

What the three editors – Laurie Hergenhan, Ken Stewart and Michael Wilding – do offer is an erudite and entertaining introduction, which guides the reader through Hopkins’s text. There is an embarrassment of endnotes, but the editors have admirably refrained from using note markers in the text, so you can refer by page as the spirit moves you. In such exhaustive footnotes, which feel the need to tell the reader who Dickens is, was there no room to offer translations from the French (and yes, the pig Latin too) for those who didn’t have Marcus and Cyril’s (and perhaps Ken, Laurie and Michael’s) classical education?

This is, however, a minor quibble. Cyril Hopkins’ Marcus Clarke is an entertaining tour of Clarke and colonial Melbourne, and the editors are admirable guides.

Comments powered by CComment