- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Custom Article Title: Colin Nettelbeck reviews 'Chasing Lost Time' by Jean Findlay

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Book 1 Title: Chasing Lost Time

- Book 1 Subtitle: The Life of C.K. Scott Moncrieff: Soldier, Spy and translator

- Book 1 Biblio: Chatto & Windus, $59.99 hb, 368 pp, 9780701181079

Born in 1889 into a well-to-do Scottish family where education and social responsibility were valued as much as social standing (his father was a lawyer, his mother a professional writer), Scott Moncrieff won a scholarship to Winchester College, where his verbal talent was honed through study of the classics and of modern literature into a formidable medium of expression. Although he failed to gain entry to Oxford and had to settle on Edinburgh for university, the Winchester connections brought him lifelong networks that had him moving readily amongst many major figures of his time: the likes of G.K. Chesterton, T.S. Eliot, Joseph Conrad, Noël Coward, Edmund Gosse, and D.H. Lawrence. At Winchester he also discovered his homosexuality. Throughout his life, he would be torn between embracing it and being tormented by it.

Belief in honour and glory was characteristic of his caste, and he headed off eagerly as a junior officer in World War I. The men under his command respected his bravery and his concern for them, and he bore his bouts of trench fever stoically. He read and wrote prolifically, perhaps in self-protection. (Examples given of his poetry strike one as well-crafted and sincere, but not in the league of Rupert Brooke or Wilfred Owen.) In 1915 he converted to Catholicism, to which, in his way, he remained faithful until his death, valuing the aesthetic and intellectual traditions, and the fact that absolution for one’s sins was generously dispensed. He appears to have harboured no resentment that the exploding shell that shattered his leg and left him painfully disabled for life came from British artillery. His greatest loss in the war was Owen, whose poetry he admired and whose person he adored: so passionately that he contrived to be sent back to the front to be close to him, only to find that Owen had been killed. Findlay believes the love not to have been consummated, nor indeed reciprocated, but Scott Moncrieff earned a reputation as a vile seducer among certain of his colleagues, including the Sitwells and Robert Graves.

While working in the War Office as an intelligence officer, and later at The Times, he turned to literary criticism. He could be a brutal critic, but it was through reviewing some translations from the French that he developed an interest in what would become his true literary vocation. His own first translations, well received, were of the Chanson de Roland and Beowulf, and soon he launched into Proust, whose postwar celebrity had crossed the Channel to England, and in whose writing Scott Moncrieff discerned ‘something great’.

‘the multiplicity of authentic documents – letters, poems, notes, diaries – allows Charles Scott Moncrieff to emerge as a vital, brilliant, conflicted whirlwind of a man’

Translation work was a perfect cover for another task he had accepted, namely to report to British authorities on developments in fascist Italy. Unfortunately, despite the biography’s subtitle, we learn very little about Scott Moncrieff the spy. On the other hand, his busy social life in Italy – first in Pisa, then Rome – is amply documented, sometimes with tedious precision. With much of the money earned from his translations going to support struggling members of his family, he managed a prodigious output during his seven Italian years. When he died in Rome in 1930 at the age of forty, of oesophageal cancer, he had completed all but the last volume of Proust’s monument, several of Stendhal’s works, Abélard’s letters to Héloïse, and a suite of Pirandello texts.

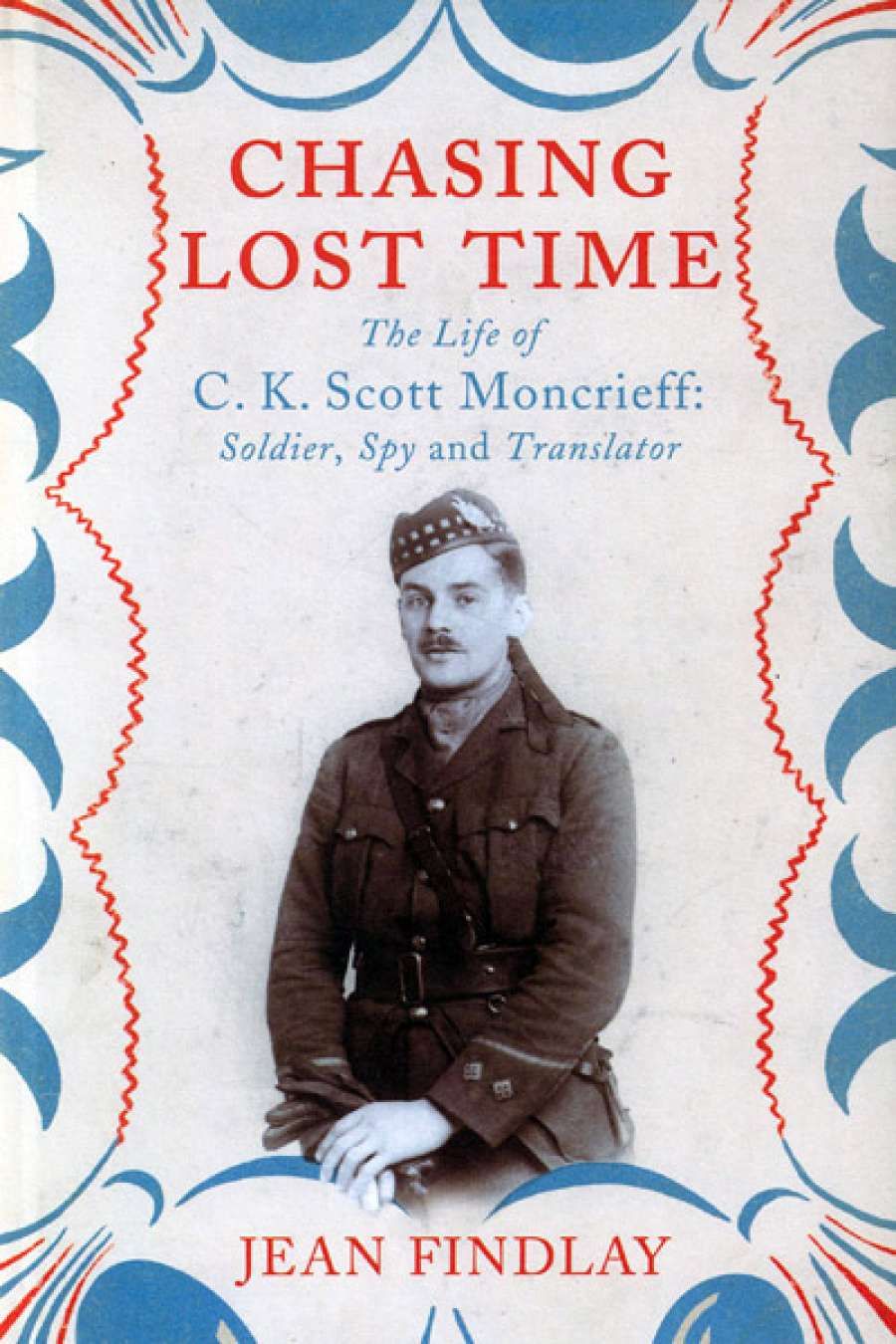

C.K. Scott Moncrieff on a visit to Winchester before the war, aged twenty-three

C.K. Scott Moncrieff on a visit to Winchester before the war, aged twenty-three

His Pirandello translations were as important to him as the Proust, though, as many of them remained unpublished, they are less relevant to posterity. In respect to Proust, beyond the complexities and ambiguities of style, there were serious obstacles to be surmounted: the original French printed texts were often downright inaccurate; while Proust was still alive, the work kept growing and changing, and with his death in 1922, the publication schedule in France became erratic. Then there was the threat, especially in Britain, that the publication of Sodome et Gomorrhe, even discreetly rendered as The Cities of the Plain, might provoke morality-based legal action. Scott Moncrieff handled these problems with stubborn persistence. Of course, there was the issue of his use of Shakespeare’s Remembrance of Things Past to skirt the untranslatable ambiguities of À la recherche du temps perdu, but, as a whole, the translation was, and remains, a triumph.

It was not the case, despite Conrad’s famous assertion, that the translation was somehow ‘better’ than the original. Scott Moncrieff found the way to create and sustain, in English, a powerful sense of the difference, the otherness of the whole Proustian imagined world and of the extreme originality of Proust’s writing. This was a historically significant literary achievement, and if it undoubtedly sprang from the translator’s keen and pained awareness of his own otherness and originality, it is also the expression of a kind of genius. It involved intense and thorough labour: one of Scott Moncrieff’s invariable habits was to test his work – every sentence of it – by reading it aloud to carefully selected listeners. One can be confident that he would have approved the revisions so finely wrought by Terence Kilmartin in 1981, based as they were on the comprehensive re-editing of the original French text. It is less sure what he would have thought of Christopher Prendergast’s later bold but voice-splitting experiment in distributing different sections of Proust’s novel to different translators.

‘In respect to Proust, beyond the complexities and ambiguities of style, there were serious obstacles to be surmounted’

Jean Findlay is herself not much interested in Proust. She includes the Tadié and Painter biographies in her reading list, but the diffidence shows up in symptomatic ways. For instance, Proust would have been deeply offended to find himself lodged in the 9ème arrondissement of Paris, rather than up the boulevard where he in fact lived, in the more prestigious 8ème. And what can one say when À l’ombre des jeunes filles en fleur is reduced to ‘young girls starting their period’? Or when, in defending Scott Moncrieff’s decision to translate Proust against the anxious objections of Edmund Gosse, Findlay earnestly opines that Gosse did not know that Scott Moncrieff’s ‘more English and Apollonian interpretation of Proust might be all it needed to give it balance’?

Still, for all its irritations and unevenness, Chasing Lost Time offers rewarding reading for its affecting portrait of its subject – ‘a tragic life lived with humour’, as the author concludes – and for its bubbling evocation of an era of British cultural life forever gone.

Comments powered by CComment