- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Society

- Custom Article Title: Simon Caterson reviews 'The Rich' by John Kampfner

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Just how different are the rich from everyone else? F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote in a 1926 short story that they are ‘soft where we are hard, and cynical where we are trustful, in a way that, unless you were born rich, it is very difficult to understand. They think, deep in their hearts, that they are better than we are because we had to discover the compensations and refuges of life for ourselves.’

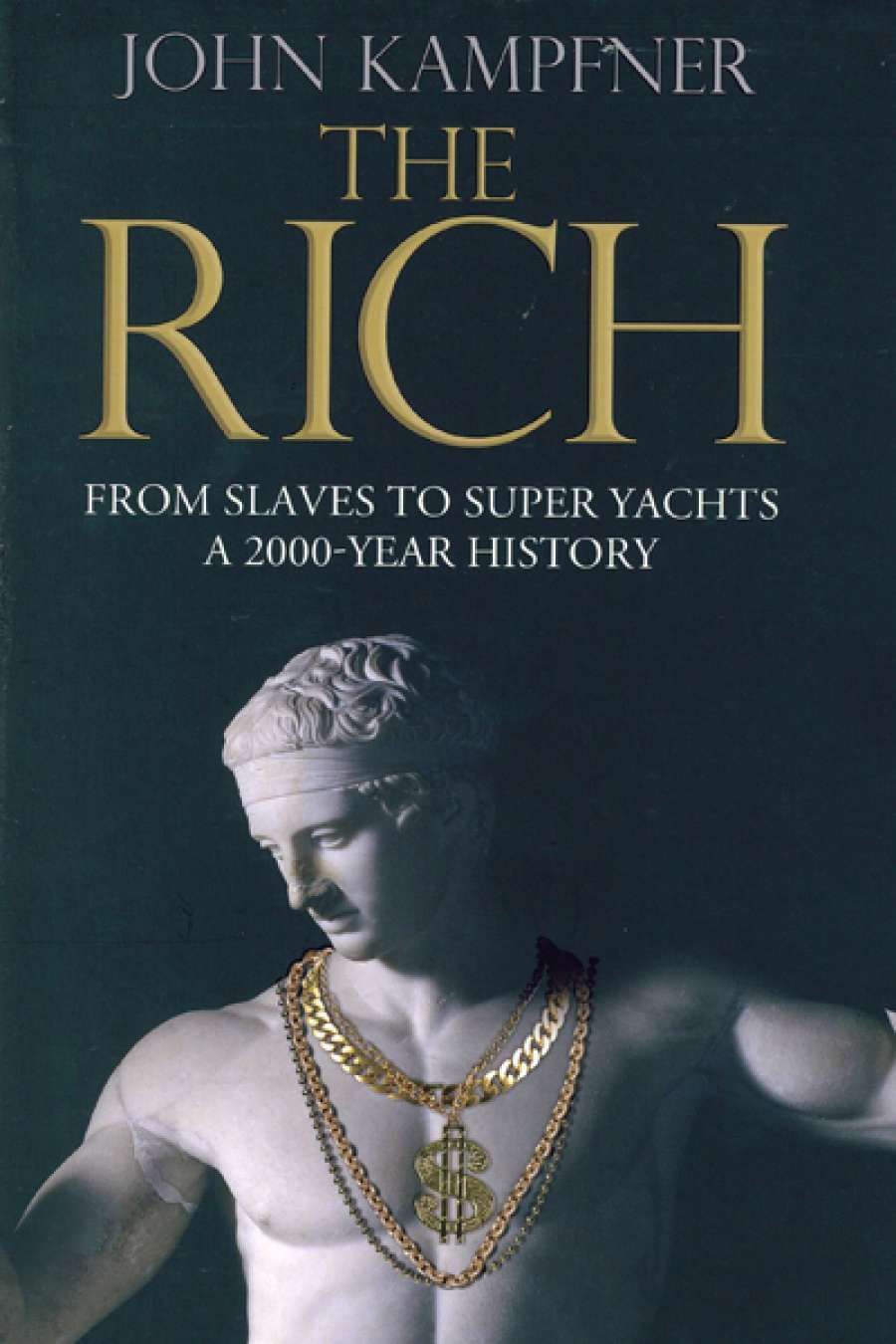

- Book 1 Title: The Rich

- Book 1 Subtitle: From slaves to super-yachts, a 2,000-year history

- Book 1 Biblio: Hachette, $32.99 pb, 479 pp

Kampfner reveals that wealthy people are no more or less predictable in their habits and behaviour than the rest of us. They, like everyone else, are only limited by their imaginations. Kampfner argues that the minds of the self-made super-rich are animated by ambition, greed, and, above all, he believes, by a fierce desire to write their own epitaph.

It should be mentioned that this is a book expressly about men. Though Kampfner considered a list of irrefutably super-rich women candidates for his history, among them Australian mining magnate Gina Rinehart and Elizabeth II, none of them could really be described as self-made. ‘It is sad but necessary to acknowledge that the vast majority of women who might be considered super-rich in history have acquired wealth through either marriage or inheritance,’ he writes. ‘For the past two thousand years it is men who have made, and hoarded, wealth in societies that have been exclusively patriarchal. Therefore, I decided to stick with my male-only list to send a deliberate message.’

Kampfner expects this situation to change in the future. He notes the rise of American women among CEOs and Chinese female business entrepreneurs. He might also have considered the case of J.K. Rowling, whose self-made wealth as one of the world’s most popular novelists reportedly has placed her on a par with the queen in material terms. Rowling could be one of the few people in history ever to become extremely wealthy without apparently treading over other people to get there.

The Rich begins with the ‘first and most archetypal member of the club of the super-rich’: Marcus Licinius Crassus. These days Crassus is probably most remembered as the Roman military commander responsible for suppressing the slave rebellion led by Spartacus in 73 bce. Crassus was not, in fact, a regular officer but a private citizen who offered to underwrite the creation of the mercenary force needed to put down the revolt.

Crassus’s immense wealth had come from property speculation in Rome, a business that at that time involved both setting fire to buildings deemed suitable for redevelopment and then supplying the only effective fire service in the city. Crassus’s firefighters would offer to buy the destroyed property at a knockdown (or burnt-down) price from the uninsured owner, and it would then be rebuilt by a team of construction workers also employed by Crassus.

One figure that Kampfner wishes to restore to a rightful place among the super-rich men of history is the fourteenth-century Malian emperor Mansa Musa. An African Muslim, Musa became astonishingly wealthy by owning or controlling all of the gold extracted from the immense deposits located in the regions he ruled over.

Depiction of Mansa Musa, ruler of the Mali Empire in the 14th century, from a 1375 Catalan Atlas of the known world (mapamundi), drawn by Abraham Cresques of Mallorca. Musa is shown holding a gold nugget and wearing a European-style crown (via Wikimedia Commons)

Depiction of Mansa Musa, ruler of the Mali Empire in the 14th century, from a 1375 Catalan Atlas of the known world (mapamundi), drawn by Abraham Cresques of Mallorca. Musa is shown holding a gold nugget and wearing a European-style crown (via Wikimedia Commons)

‘Social convention required the wealthy to provide goods to the poor whenever they travelled,’ explains Kampfner. ‘This form of charity was the closest society came to the provision of even the most basic income. The more a man was worth, the more generosity was expected of him (a stricture that would be adopted centuries later by the likes of Andrew Carnegie and Warren Buffett).’

A further parallel between Mansa Musa and the present day can be seen in the rise of the Russian oligarchs, who are allowed to exercise monopolistic control over Russia’s vast natural resources and shift their wealth offshore without hindrance from President Vladimir Putin as long as they support him politically. The unholy and seemingly inevitable alliance between political and economic power is not confined to non-democratic societies.

Kampfner notes a similarity between Russian oligarchs and the Spanish conquistadors who in the sixteenth century began systematically exploiting South America, destroying whole indigenous populations and civilisations as they went. As both the conquistadors and oligarchs demonstrate, the surest way to become super-rich is through the unfettered acquisition of natural resources. What Kampfner terms ‘extractive colonisation’ also, in his view, characterises much of the activity of Western multinationals in the Third World.

Kampfner concludes by pointing out the eternal ambivalence evident in the attitude of ordinary folk towards the very wealthy, a mixture of both admiration and resentment. As Midnight Oil once pointed out in the lyrics to one of their songs: ‘The rich are getting richer / The poor get the picture.’

Comments powered by CComment