- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Language

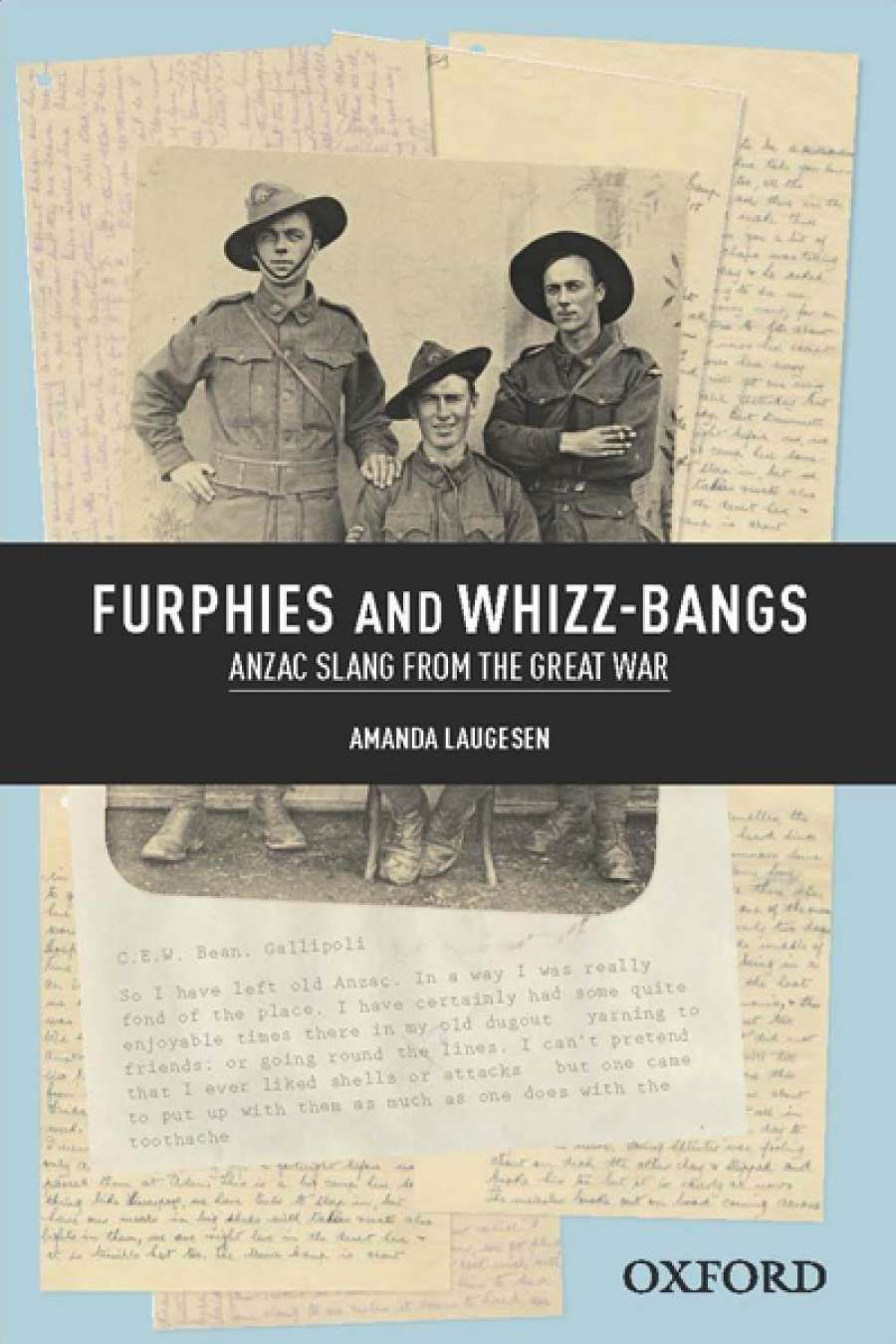

- Custom Article Title: John Arnold reviews 'Furphies and Whizz-Bangs: ANZAC slang from the Great War' by Amanda Laugesen

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The Great War produced its own idiom and slang. Many of the new words and phrases created during the long conflict, such as ‘tank’ and ‘barrage’, became part of standard English, although often with a different nuance of meaning.

The recording of Australian soldier slang was seen as important at the end of the war. It was recognised as being integral to the unique character of the Australian soldier and linked to the official war historian C.E.W. Bean’s characterisation of the Australian soldier as the bronzed bushman and an outstanding fighter with a disdain for authority. In 1919, W.H. Downing published Digger Dialects; he described the slang he had collected as ‘a by-product of the collective imagination of the A.I.F.’. In the early 1920s, A.G. Pretty, chief librarian at the Australian War Museum, later the Australian War Memorial, compiled a ‘Glossary of Slang and Peculiar Terms in Use in the A.I.F.’. Amanda Laugesen (now the director of the Australian National Dictionary Centre at the Australian National University) has previously edited an online version of Pretty’s ‘Glossary’ and in 2005 published Diggerspeak: The Language of Australians at War.

- Book 1 Title: Furphies and Whizz-Bangs

- Book 1 Subtitle: ANZAC slang from the Great War

- Book 1 Biblio: Oxford University Press, $32.95 pb, 254 pp

In Furphies and Whizz-Bangs, Laugesen makes a valuable contribution to the current output of books on the Great War. It is both a study of Australian English and a book that adds to our understanding of the daily lives of the 400,000 or so Australians who served in the war.

The book can be read as a historical survey or used as a dictionary of World War I Australian servicemen’s slang. It is arranged by thematic chapters, each with a brief introduction followed by an alphabetical listing of slang terms pertaining to the relevant chapter. The meaning and origin of each slang word or phrase are followed by examples of its use in soldiers’ diaries, letters home, and the many battalion or troop ships magazines. The author has made excellent use of the National Library of Australia’s Trove database and its collection of digitised Australian newspapers to find contemporary examples of slang usage. How the nature of newspaper research has changed!

An alphabetical word list at the end of the work provides an index to where the 379 words and phrases are discussed and defined in the book. One is struck by both the inventiveness (and humour) of many of the slang terms. ‘Jack Johnson’ was the name given to a type of heavy German artillery shell used on the Western Front that emitted a dense black smoke. It was named after the black US heavyweight boxer, known as the ‘Big Smoke’, who had fought and soundly defeated the white champion, Tommy Burns, in Sydney in 1908. A ‘short-arm parade’ was used to describe the public penis inspection of soldiers for possible venereal disease, while ‘deep thinker’ described someone who joined the AIF late in the war, implying that they had thought long and deeply before deciding to enlist. ‘Roo de Kanga’ was a sign (now in the Australian War Memorial) placed on a street in Péronne after it had been captured in 1918, ‘roo’ being a play on ‘rue’. An ‘Aussie’ was a term used by other nationalities to describe Australian soldiers, but it was also used by the men of the AIF to describe a wound bad enough to get them invalided back to Australia. Many wished for an ‘Aussie’.

Much of this was Bulletin-style humour. But using slang was also a way of coping with death and the horrors of war. So a bayonet became a ‘toothpick’ and death had many terms, possibly in an attempt to try to depersonalise the experience, such as ‘to get the full issue’; ‘hanging on the barbed wire’; ‘E’s gone west’; and ‘E’s chucked a seven’ (from the game Hazard: if you throw a seven you are out of the game).

The definition given to the word ‘furphy’ does prove the indirect link to the Australian author Joseph Furphy, but only to the family business of making water carts, not his famous novel Such is Life (1903). The term originated soon after the war broke out in August 1914 and the first Victorian enlistments were camped at Broadmeadows. The Furphy water carts were housed near the latrines. These were places where men could talk freely away from their officers and commanders and soldiers tended to spend more time there than was necessary for their normal functional use. They would chat, gossip, and discuss likely embarkation dates and, later, plans for attacks or going ‘over the top’. Rumours inevitably flourished and became known as ‘furphies’ or ‘latrine rumours’ originating from the ‘latrine wireless’.

A Furphy water cart hitched to an Australian Draught Horse. A small girl is riding on the horse's back holding the reins, and a small boy is resting on the left shaft also holding the reins, 1939 (Wikimedia Commons)

A Furphy water cart hitched to an Australian Draught Horse. A small girl is riding on the horse's back holding the reins, and a small boy is resting on the left shaft also holding the reins, 1939 (Wikimedia Commons)

‘Over the top’ is one of the many phrases from the war still in use today, although with a somewhat different meaning. It is now used to convey a meaning of ‘too much’ or ‘a bit rich’ in relation to a claim or activity. In the war it was a synonym for an attack, leaving the relative safety of the trenches and climbing over the top to charge across no man’s land to fight the enemy. Brophy and Partridge in their Songs and Slang of the British Soldiers, 1914–1918 (1931) note that the phrase originally had a second part to it: ‘over the top and best of luck’. But, they dryly comment, ‘as it became increasingly obvious that there was no luck involved the latter half of the phrase was dropped’.

These examples from the many slang definitions given in Furphies and Whizz-Bangs show how words both originate and evolve and why lexicography is not a dry subject.

Comments powered by CComment