- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Gambling was and is an economically and culturally important activity in many urban African American communities, and ‘numbers’ was from the mid-1920s a ‘full-blown craze’ in Harlem. It was a complicated method of gambling on a set of three numbers generated by an apparently incorruptible process. The numbers, posted each day by the New York Clearing House, a financial institution just a couple of blocks from Wall Street, related to arcane matters such as daily clearances between banks and the state of the Federal Reserve, but they were eagerly awaited, published in news-papers and deployed for quite different purposes. Numbers ‘bankers’ roamed the streets collecting small ‘investments’ from customers who then collected a return if their three numbers came up. Regular small bets from large numbers of people generated a lot of money, and successful numbers operators became rich. Numbers had a turnover in the tens of millions of dollars a year in Harlem and, remarkably, became the enterprise ‘with the largest number of employees and the highest turnover’ in that legendary part of the city.

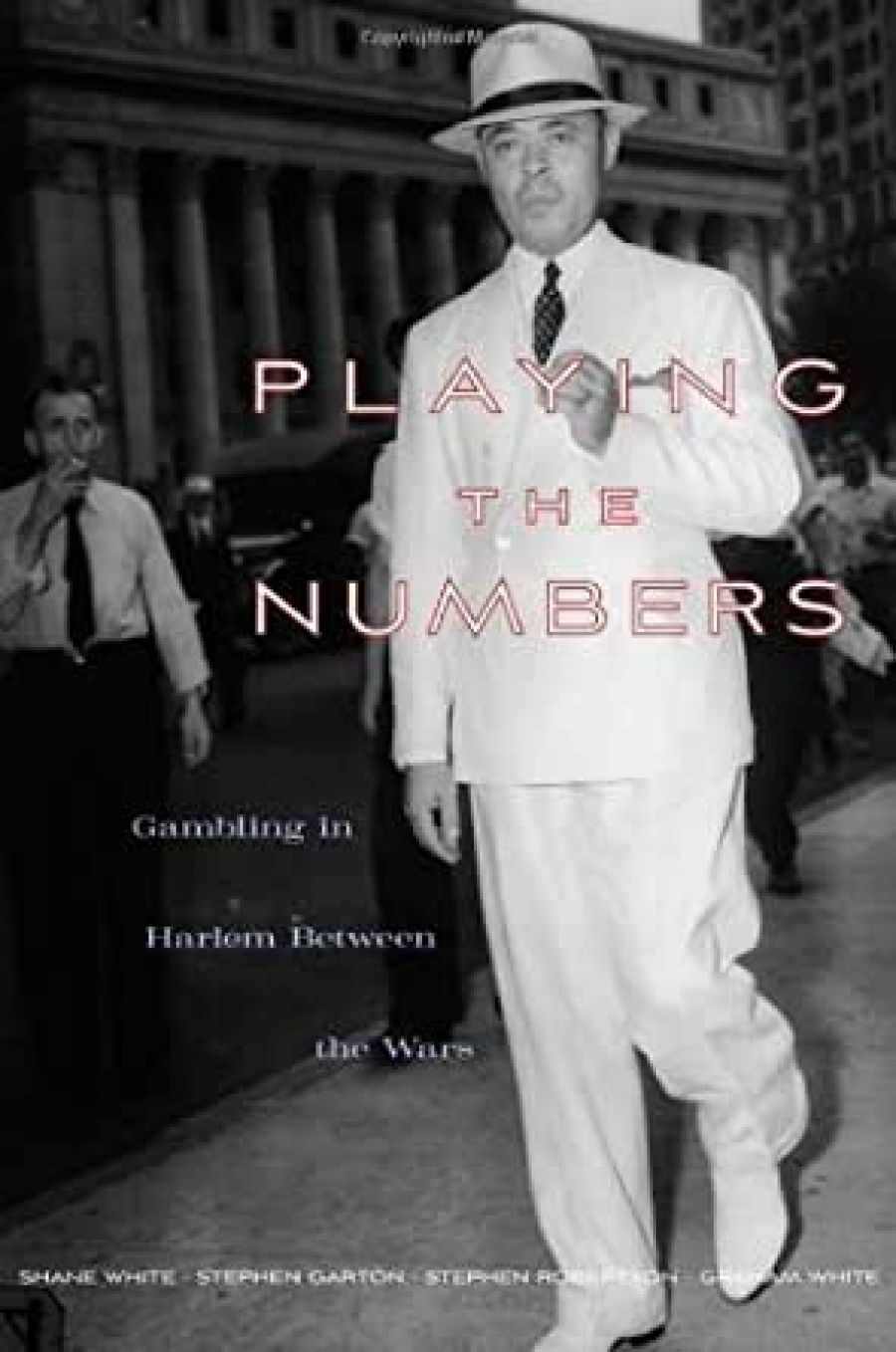

- Book 1 Title: Playing the Numbers

- Book 1 Subtitle: Gambling in Harlem between the Wars

- Book 1 Biblio: Harvard University Press, $26.95 hb, 299 pages

Playing the Numbers: Gambling in Harlem between the wars, written by four historians at the University of Sydney, brilliantly reconstructs the world of the numbers trade, showing how it provided, for at least a decade and a half, a space for an African-American entrepreneurship that mirrored, in a gaudy and distorting way, the mainstream financial institutions and activities of the city. There is astute attention throughout the book to this shadow relationship to mainstream commerce – not just the deployment of the language of ‘bankers’ and ‘investors’ or the use of data from financial institutions, but the equipment and business practices needed to cope with the sheer size of the trade.

Numbers bankers were modern entrepreneurs who drove big cars, modelling the life to which many of their customers aspired. There is much remarkable and admiring detail about the careers of colourful figures such as Stephanie St Clair, Bumpy Johnson, and Casper Holstein, Harlem’s numbers Kings and Queens, the larger-than-life characters who ran the business before it fell under the control of more ruthless and ambitious white ethnic criminal syndicates. Playing the Numbers is thus, in one sense, a lament for a lost moment when the black metropolis had its own financial institutions and some sense of autonomy; the best of the numbers bankers were ‘race men’ who donated back into community institutions and lent money to those who needed it. There is an all-too-familiar story here of the economic rationalisation and consolidation of an industry. In this case it was a tragicomic story, with plots along the way for several crime movies, but in the end the process of making the business more efficient took it out of local control and channelled both the profits of, and employment in, the industry to whites.

The modernity of the numbers business was of course built upon the distinctly unmodern beliefs and hopes of its customers. Playing the Numbers offers glimpses of the ordinary numbers players and insights into what made them willing to hand over their hard-won money for a chance at a (relatively) small fortune. Numbers players purchased dream books to help them translate their dreams into lucky numbers. They were vulnerable to the various scams and cons associated with the numbers trade because of their underlying willingness to believe that some insider secret could unlock the otherwise mysterious wealth and power of the white world. Most African Americans, the authors argue, ‘simply refused to accept that there was a distinction between numbers and the Stock Exchange’. But the customers never appear here simply as dupes. The book concludes that the optimism of ordinary African Americans, ‘the sense that justice would be done and that they would hit the number, was one of the distinctive factors animating black culture’.

The research underlying this short and elegantly written book is extraordinary. Years of detailed work in New York judicial and legal records, as well as in newspapers and literary sources, makes this an almost uncannily well-informed book. Connections are followed up, people identified, outcomes known. This is history as work of art, a dazzling demonstration of what can be done with sources – such as lower court prosecutor records – so voluminous and so miscellaneous that they have never been mined in this way before. Much mundane history has been written on important subjects; in the United States, for example, presidential history has long been one of the most barren fields of historiography, often no more than a higher form of celebrity gossip, tediously oscillating between hagiography and debunking. There is, on the other hand, some great history written on apparently obscure topics; microhistory as art. Playing the Numbers falls into the latter category, although by the end of the book it is clear that this is not a small but rather a hidden topic. Gambling and numbers pervaded twentieth-century African American urban life to such an extent that what becomes astonishing is how little attention they have received from historians who have been more preoccupied with the cultural aspirations of the Harlem Renaissance and the social history of the ghetto. The authors have conducted this research from Australia; that they offer some insights into the process of research and their own journey of discovery along the way will only add to the pleasures of this book for Australian readers.

Comments powered by CComment