- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: A very long party

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Marry an artist? Never! So I always thought, and reading these autobiographies does nothing to change my prejudice. Married to artists, both Judith Pugh and Irena Sibley spend a good deal of their time cooking and, even more, socialising. Not that they mind. Judith declares that ‘cooking was my deep pleasure’, essential to the story of her life with Clifton (‘Clif’) Pugh. Irena concedes facetiously, ‘it’s too hard painting pictures. It is easier to bake cakes.’ The importance of food is apparent in the chapter titles. Eleven of Sibley’s chapters refer to food, while all of Pugh’s have subheadings that, typically, jumble up evocative ingredients.

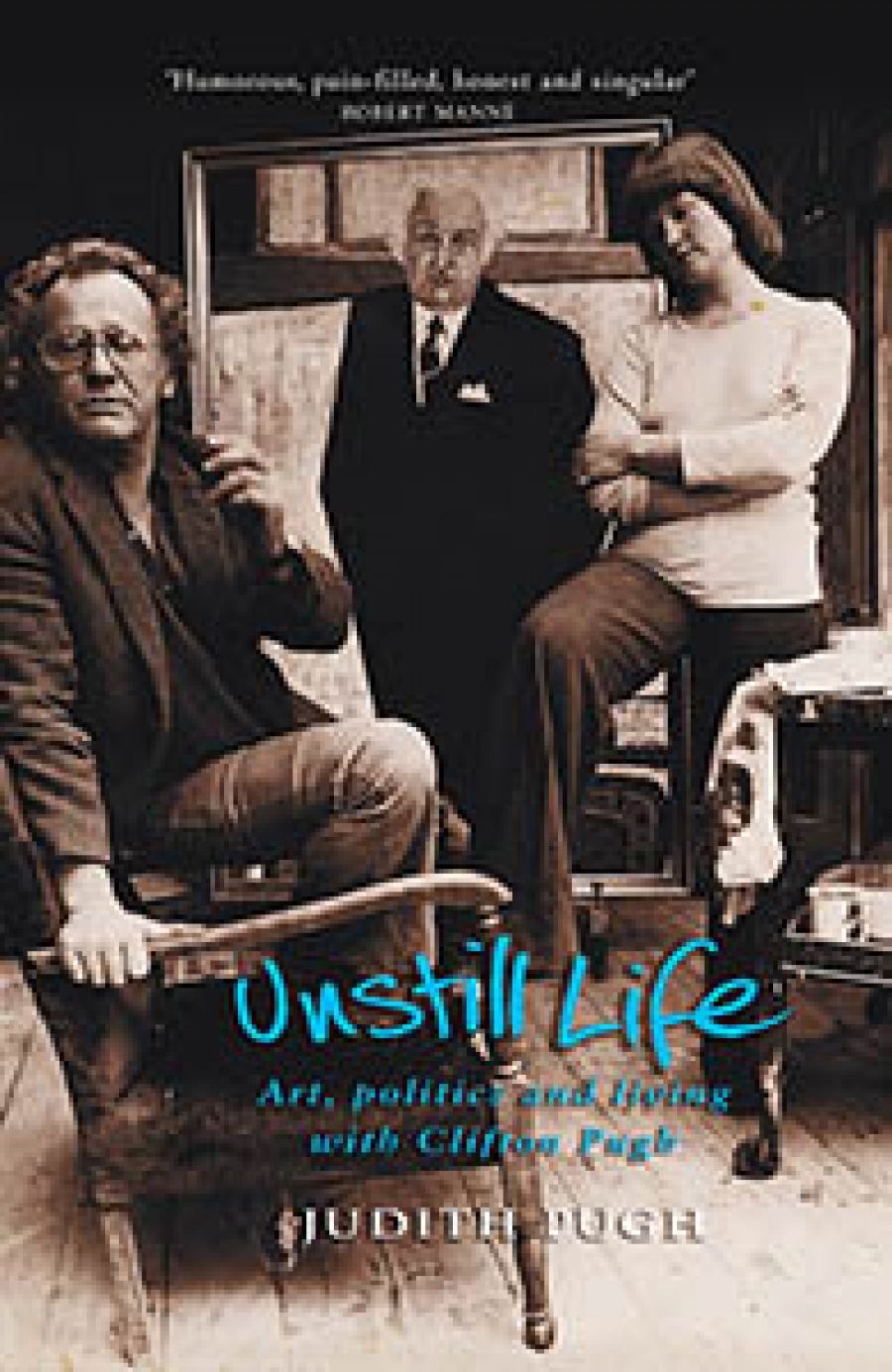

- Book 1 Title: Unstill Life

- Book 1 Subtitle: Art, politics and living with Clifton Pugh

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $32.95 pb, 360 pp

- Book 2 Title: Self-Portrait of the Artist’s Wife

- Book 2 Biblio: Lytlewode Press, $60 hb, 306 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 2 Cover Path (no longer required): images/ABR_Digitising_2022/Jan_Feb_2022/sibley self portrait.jpg

When the time and place of these two books collide, when the Sibleys live at the Pughs’ home at Dunmoochin, Irena cooks a duck, marinaded in vodka, orange and apricot jam, although they end up eating one of Judith’s efforts. Judith’s approach to food is, as with everything, political. She writes of her trail-blazing honey, soy and ginger chicken, considered ‘exotic’ at the time, and of Dame Mabel Brookes’ recipe for crème brûlée, perfect for entertaining important guests.

For Irena, cooking was a significant aesthetic as well as domestic, and even economic, occupation. Her regard for the pure intensity of taste, colour, and fragrance in fruit goes back to her Lithuanian grandmother. Plums, leaves, duck, dumplings, lemons, and meal upon meal of authentic food festoon the pages. Characteristic of her aestheticism, the last meal she describes is served at a table set all in green. She observes Andrew Sibley’s daily painting rituals and describes his studio, with its ‘small Baltic pine chest, freshly picked marigolds … in a white ceramic jug, next to which is a large bowl of lemons’. Fruit and flowers make one of his paintings ‘look like a shrine’. Irena’s world assumes iconic shapes; the quality of simplicity she seeks takes on a symbolic intensity. Never very far away are the lessons and trauma of her early experiences, when the family fled from the Russian invasion, which she recalls at the beginning of the memoir with a mix of terror and charm.

While trained as an artist, Irena doesn’t paint. Teaching full time and attending to Andrew and two sons overwhelms her: ‘There is no empty space either around me or in me … I teach, I cook, I dream, I am loved.’ But, encouraged by Andrew, she writes and illustrates childrens’ books, with much success. Apart from the death of their close friend, the legendary George Baldessin, and Andrew’s momentary lapse in having an affair, Irena presents their life together as seamless and celebratory. Life, she writes, ‘appears to be one very long party’.

For Judith Pugh, too, life with the gregarious Clifton Pugh was one very long party, but a more serious one, with heavy-duty networking. Judith is proud of her part in Dunmoochin at Cottlesbridge, a haven for wombats, kangaroos, politicians, and artists. A model for conservation and alternative life styles, when ‘life style’ was a new phrase, its parties became ‘a sort of mud-brick salon … a hotel for itinerant politicians’. She relishes its risqué goings-on. We hear about the communal nakedness that was habitual and about encounters with the less liberated, including a couple of corporate knights who turn up unexpectedly. ‘Oh shit, I forgot, a new portrait client,’ exclaims the naked Clif.

The names of an illustrious, if patchy, intelligentsia engorge many of the pages: such as Clement Greenberg, Gough Whitlam, a minister of planning from Nigeria and, of course, artists such as John Brack, John Olsen, and Fred Williams. But the main subject is Judith’s musings on the power relations between herself and Clif. He told her what to do; she cooked, kept house and entertained, looking after the visitors and clients. There was no need for her to earn money. Despite the sexism of the 1970s, her voluntary subjection to Clif is remarkable, especially given her education. She emphasises her helplessness, how she ‘was used to watching quietly, the assumed bimbo’, and referring to herself as ‘the pale inconsequential girl meeting guests’. Was it liberated or not for her to model for the male artists? Later she reflects: ‘across the years I see myself as a tool, advertising Clif’s masculinity.’

Judith makes much of her role as somehow integral to Clif’s portrait painting, explaining that the ‘structure that kept our relationship going for so long … was what we did together with the portraits’. Chatting to Clif’s sitters, she helped relax them, enabling Clif to see more of their character and leaving him free to paint. Judith was always practical and dogged, a born strategist. When Clif suffered a heart attack in Bali without a plane ticket home, she door-knocked the guests in their hotel and rallied support that forced the airline to fly him home. Only too aware of Clif’s problems with alcohol, she berated their house-guest, Christina Stead, for late-night drinking sessions.

Art for Judith is political, and politics, for her, is about day-to-day tactics. Cohabiting with Clif spurred on her activism. In an enlightening account of the new Labor government she is highly critical of what she perceives as Whitlam’s fatal lack of patience. Like Clif, who was identified with the ALP, her affiliations were extremely flexible. She comments that Clif was not only an artist but a small businessman, a capitalist entrepreneur. She has no problem that so many of his clients were bankers and conservative politicians; that he often swam with Harold Holt. She manoeuvres an introduction to Buckingham Palace, landing Clif the gig to paint Prince Philip’s portrait.

Anyone who has experienced the economic consequences that follow the demise of a major relationship will have been watching for signs of how Judith was negotiating her financial situation. Referring to Clyde Cameron, she notes ‘long before I could, he saw how my options were being limited, how powerless I was’. Gradually it dawns on her that something is amiss, that, as a de facto spouse, she has few rights. In Sydney, soon after Judith had saved his life following a heart attack in Bali, Clif refuses to give her traveller’s cheques to buy warm clothes.

The most affecting moment of her memoir comes at the end of her affair with Don Dunstan, in the harrowing account of the birth of her stillborn baby in 1972. In scenes of medical mismanagement and callousness that defy belief, the doctor refuses her request to hold her baby and later even to bury it. She only sees it from afar, a ‘tiny pearly body’. Her incompetent anaesthetist manages to break her front teeth while applying a mask to put her to sleep. After this nightmare, she is sterilised and later, at the request of Beatrice Faust, becomes an advocate for abortion rights.

Other memories, however, are disturbing in a less sympathetic way, especially her all-forgiving accommodation, even assimilation, of Clif’s weaknesses, most obviously his wartime conduct. When he was part of the occupying force in Japan, Clif safeguarded himself against disease by buying his own brothel with black-market money. Judith uses this to explain, unconvincingly, that he was uninterested in having children because his ‘first sexual experiences were with a Japanese woman he owned, in a brothel he owned’. Better known are the diary entries from his time in New Guinea, included in Traudi Allen’s 1981 biography, which reveal a sadistic relish in the suffering he inflicted on his Japanese victims. Judith herself records that Clif deliberately burnt Japanese corpses ‘to see if they would burn easily, if human flesh smelled like meat. They did. It does.’ Weirdly, she includes ‘the smell of burning flesh’ in the subheading for that chapter, along with fish and chips. Artists may be forgiven a certain objectivity, but surely this experiment differs from, say, Monet’s well-known clinical reaction to his wife’s face on her deathbed. Afterwards, Clif famously reacted with horror to war and to what he regarded as the effects of army training on his personality; his anti-war stance became central to his public persona.

Clif’s way of ‘dealing’ with his traumatic memories was to drink and become violent. He ruminates repeatedly on the shooting of Japanese prisoners of war; Judith suspects that he was the one of the murderers. Only after he vents his anger at both her and Clyde Holding does Judith see ‘what was happening to me. I told Clif I wanted to leave.’ But she stays, in the hope that, ‘if he could see and bear his own dark truth we could get through it.’ When she does attempt to get him to face it, she pays a price. Clif physically attacks her (‘the only occasion he really laid into me’). Judith reflects at some length on the many unequivocally selfish ways in which he conducted his life. The cumulative effect is to emphasise her role as an emotional crutch, complicit in his self-indulgence. Instead of offering a clear perspective on Clifton Pugh, the memoir records her own submersion in his personality, fame, and way of life. This is, of course, autobiography.

Both these books demonstrate the chameleon manoeuvres that many women willingly adopt to survive living with others. Sibley’s limited edition showcases exquisite illustrations and colour photographs, while Pugh’s book features spontaneous snapshot views, including several of her own enthusiastically naked moments. While the gentle simplicities of Irena Sibley’s prose enclose and limit her vision, Judith Pugh writes in crisp but jangling fragments that are never quite able to contain their subject. Like the elusive Dunmoochin landscape that shimmers about her daily life, her account is sprawling, confusing, and unresolved. Yet her speculative musings, confessions of naïveté and admission of failings are the stuff of good autobiography. Likeable or not, admirable or not, they touch on a larger perspective, the capacity for self-reflection. It is perhaps a testimony to her abilities in this regard that she reveals how deeply she sunk her persona, for better or worse, in that of another and has been able to write with verve and considerable, if imperfect, insight about the experience in retrospect. Marrying an artist still seems a risky business.

Comments powered by CComment