- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Travel

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

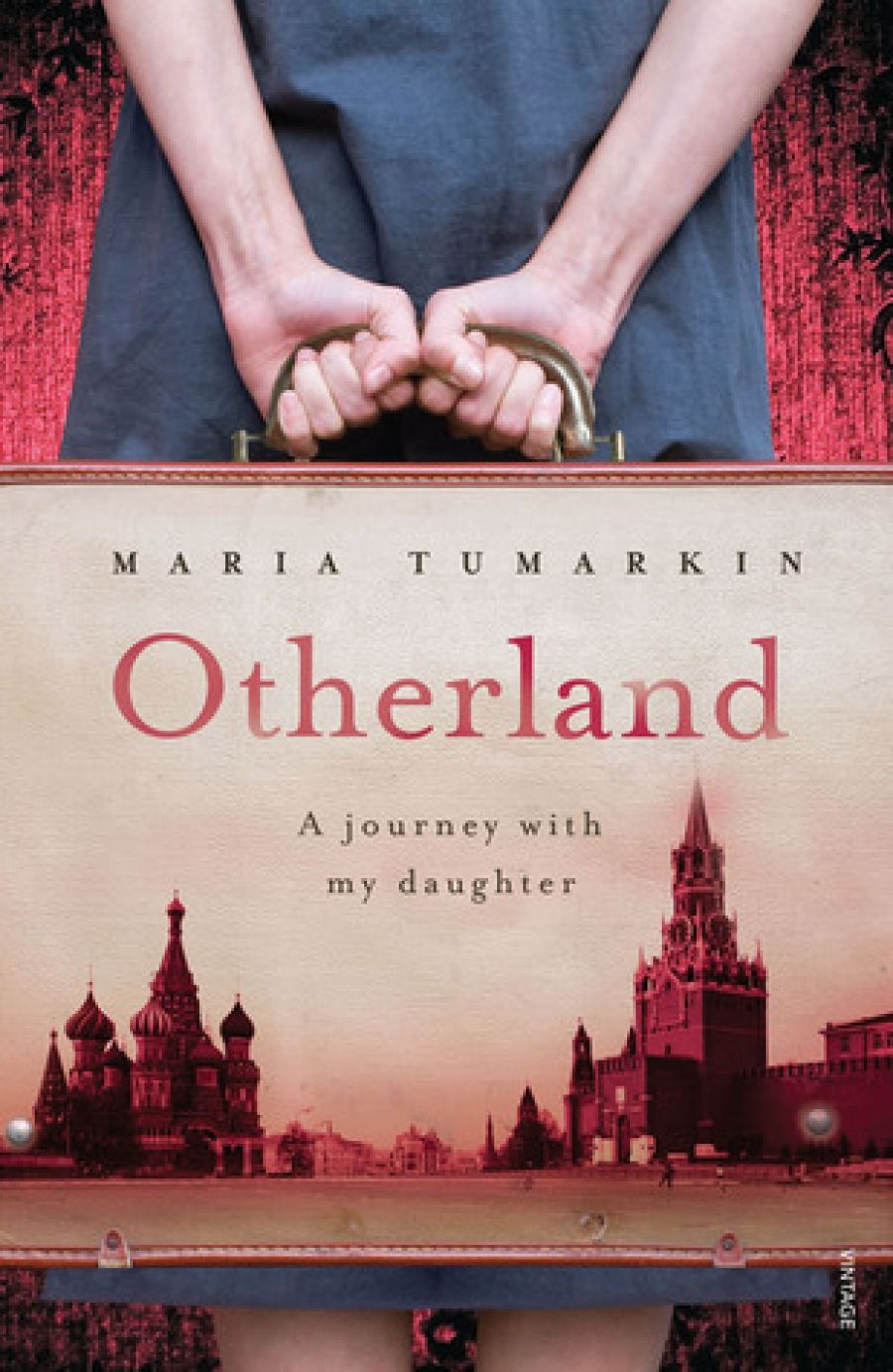

Let no one say that all travel memoirs fall into the same predictable box. Otherland and Mother Land, two such works from Melbourne writers, may enjoy rhyming titles and pluck similar strings, but their styles could hardly be more dissimilar. The first, a new book from Maria Tumarkin, describes a journey to her Ukrainian/ Russian country of birth with her twelve-year-old daughter in tow; the second, a 2008 evocation by Dmetri Kakmi, follows a revisiting of his childhood on a Turkish-Greek island. Of it I wrote in The Age: ‘Always a beautiful, evocative and carefully crafted reconstruction of a past life generically familiar to many migrants, Mother Land outshines the plethora of similar memoirs because it consciously operates at two levels: the narrow focus, limited characters and humdrum events are transcended and elevated to a universal myth of loss’ (16 August 2008).

- Book 1 Title: Otherland

- Book 1 Subtitle: A journey with my daughter

- Book 1 Biblio: Vintage, $34.95 pb, 320 pp

Tumarkin’s central purpose in making another trip – not her first since her emigration to Australia at the age of fifteen – is to expose Billie (the daughter, named for Billie Holiday) to her family history and inheritance. Left in the care of a Melbourne babushka is Billie’s small half-brother Miguel, neither of the two fathers being in the picture any more. Typically, Tumarkin makes a virtue of the situation: because Billie has never met her biological father, she ‘has already learned the rudiments of emotional self-defence – bravado, deflection, improvisation, acute story-telling’.

Transparent pride in the child’s ‘early recognition of the power of language, her innate stubbornness and her preoccupation with justice’, not to mention her outstanding ability to sing like her namesake, blinds Tumarkin to the fact that her maternal admiration sometimes does Billie something of a disservice. I am sure that in the flesh the girl is not the pain her mother can unconsciously turn her into on the page. ‘These damn writers,’ mutters the pre-conscious twelve-year-old, weeping over the last chapter of yet another book. ‘Why do they torture us, Mum?’

The significant leg of the Tumarkins’ journey begins in Vienna, when the efficient Austrian Airlines flies direct to chaotic Moscow, these days with a permanent traffic jam, but also the home of glamur, the capitalistic expression of conspicuous consumption that modern Russians have confused with the romantic shimmer of Western ‘glamour’. Tumarkin’s observation that, in today’s Moscow, money acts like a force of nature, ‘irrational, erupting, unstoppable, primal’, is powerful and, unfortunately, spot-on. It produces an arresting disquisition on the Soviet experience and its complex, unpredictable, even life-affirming effects on the Russian psyche.

Tumarkin’s conclusions, as she measures, compares and reflects on the differences between then and now, are among the most thought-provoking aspects of her book, particularly as she does not rely solely on subjective impressions, interspersing among her own judgements numerous apperceptions from other writers: Pasternak, Akhmatova, the Mandelstams, the contemporary Boris Pelevin. At the same time, her friends feed her the kind of close-hand information that only those who live in situ can be aware of. Their sombre observations reveal archives closing their doors to independent researchers, school textbooks being rewritten, and historians, in the wake of journalists, being arrested. A television program modelled on the BBC’s 100 Greatest Britons included Pushkin and Dostoevsky among its top twelve Russians, but also Lenin and Stalin. The outright winners of the respective programs were Winston Churchill and Russia’s legendary medieval hero Alexander Nevsky. Both countries appear to idolise military leaders above all others.

Tumarkin spent her childhood in the town of Kharkov, at a time when Ukraine was part of the USSR. Mother and daughter opt for nostalgia via the ancient capital, Kiev; but before embarking on the journey south, they visit both St Petersburg and Leningrad. Yes, of course these are geographically the same place, but they are historically so different that the author awards them separate chapters under each name. As with Kiev, Tumarkin (currently a Research Fellow at an Institute for Social Research in Melbourne) uses major cities as an opportunity to give her readers gobbets of interpretative, if potted, national history. Unlike the literary allusions to poets such as Mandelstam, Brodsky or Elena Schwartz, these summaries will offer little to anyone already familiar with Russia’s past, but they will no doubt be of interest to those who read Otherland primarily for its illumination of emigration and returns to origins. Other readers will identify more with the major sub-theme running through the book, Tumarkin’s high but wary expectations of her child’s responses to foreignness. Too wise to assume that Billie will react favourably to everything she is exposed to, Tumarkin watches closely and analyses minutely as her daughter absorbs, or does not absorb, the shock of the old.

This issue raises its prickly head markedly in regard to one of Tumarkin’s most dreadful vignettes, a full and detailed account of what happened at Babi Yar, the giant ravine which became a grave for thirty-three thousand Kievan Jews. The mix of historical information, human courage and shocking grief is profoundly moving, but the subject is a daunting one to discuss with Billie. However, as is typical of the author, such materials, once quarried, are personalised; even the English language becomes in Tumarkin’s hands a defiantly idiosyncratic tool (e.g., mothers, children and Jews are always ‘mums’, ‘kids’ and ‘kikes’). Thanks to this highly individual voice, Otherland is another smart and provocative read.

Comments powered by CComment