- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Sport

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Furore in Moscow

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Almost thirty years on, in a post-Samaranch age, when the wealthy Olympic movement mimics the United Nations in world affairs, the 1980 Moscow Games resemble prehistory, especially for Australian athletes, officials and spectators still revering 2000 Sydney successes. Yet as Lisa Forrest recounts, the Moscow boycott shredded the traditional views of Australian sports people, ensured national sport would become more politicised, and produced shameful behaviour all round.

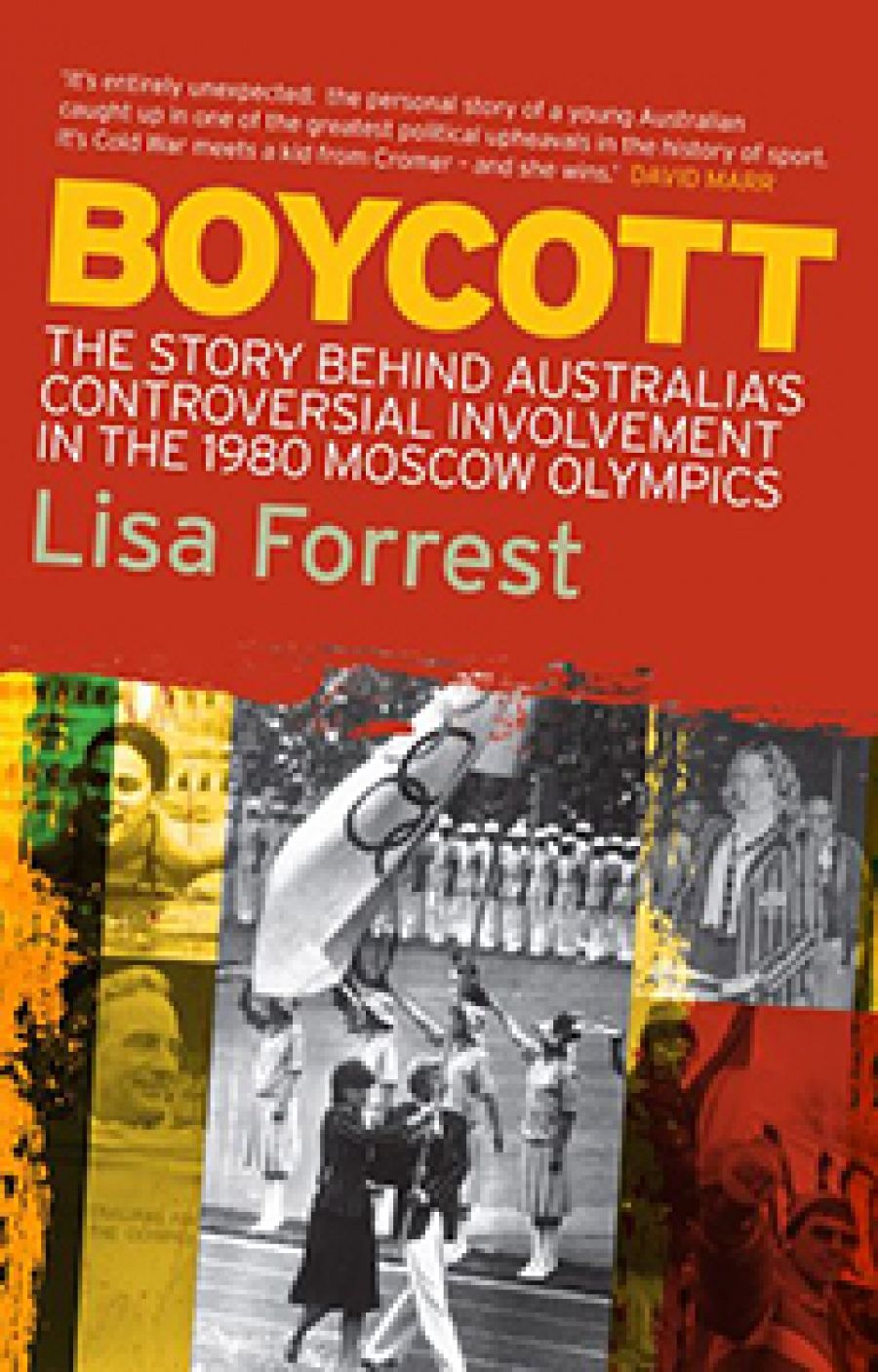

- Book 1 Title: Boycott

- Book 1 Subtitle: The story behind Australia’s controversial involvement in the 1980 Moscow Olympics

- Book 1 Biblio: ABC Books, $35 pb, 272 pp

Forrest’s book is enlightening. It reveals the ordeals undergone by élite athletes and the fierce interpersonal battles that exist within sports organisations but are little understood in the wider world. It considers, indirectly, the immense changes to sport through its professionalisation, and traces the chasm between an athlete focused on winning and the world of global politics, and the complexities of connecting both spheres. It demonstrates the muddle-headedness surrounding the debate about the link between politics and sport.

Forrest, who writes well, succinctly describes the formative affairs preceding the Moscow boycott after the 1979 invasion of Afghanistan. But either she has attempted too much or she needed more space. This is memoir, growing-up diary, élite insights and administrative history meeting sport-in-change and generation gap.

The best sections are marvellous. Chapter Seven begins, ‘Mum doesn’t remember the exact day of the first death threat’, then describes graphically the severe stress that athletes endured from a baying media and a rabble-roused public. For a young teenager, this was frightening and confronting, and Forrest describes movingly her experiences and those of other athletes.

One of the book’s strengths lies in the extensive interview material drawn from athletes, administrators and politicians. These yield nuance and revelation. Steve Foley, the diver, recalls meeting a client at the bank where he worked (another reminder of former times for athletes). In 1979 the Polish millionaire funded Foley for a training trip, but then asked him to boycott Moscow in 1980. The man told Foley his family had escaped Poland following the Soviet invasion. Sympathetic, but refusing to agree, Foley then feared for his job because of the client’s importance. A few days later, the man apologised to Foley, in front of the branch manager. In the midst of madness, decency prevailed in some quarters.

In such a sprawling story, generalisations are inevitable. The largest one surrounds the central debate: why should athletes sacrifice their careers when Australia still sold minerals, wheat and wool to the Soviet Union? As told here, that debate’s trajectory has changed little in intervening years, despite the burgeoning literature on sport and politics, and on the philosophy of sport. That is understandable, in part: after all, the imminent Beijing Games have prompted similarly fuzzy discussion about the links between sport and human rights (the big change, of course, being the massive conjoint economic interests shared by the IOC and the corporates, matched with the symbolic goals pursued by the Beijing politarchy). Unfortunately, Forrest’s resulting depiction has innocent hero athletes staring down unfeeling and self-interested bureaucrats:

We were rebels. We were plainly anti-establishment. We were on a crusade to save the Olympics. And we were underdogs who would not be beaten by a group of boorish, aging, élitist conservative fuddy-duds.

If only the world were that simple. The evidence here itself denies the characterisation. The Australian Olympic Committee’s members determined to defy the Australian government’s call by just one vote. That came from Lewis Luxton, a former delegate to the IOC, who originally intended voting for the boycott. On the morning of the meeting, he was lobbied heavily in a phone call from Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser. He took exception to this, so one of the ‘ageing élitists’ changed his vote to allow Lisa Forrest and others to compete in Moscow. (Curiously, Luxton does not appear in the Dramatis Personae list in the review copy).

One obvious weakness is that the story, engaging and insightful as it is, is constructed by interview and newspaper material without recourse to important archival sources in Australia and elsewhere. There are hints here, for example, that Fraser and Andrew Peacock, his foreign affairs minister, held very different views. Records declassified under the thirty-year rule will be enlightening in three years’ time.

Even Luxton’s changed vote did not end things, though, and there are two particularly sad endgame pieces. The first traverses the disruption caused within athlete and organisation ranks by the government’s clandestine payments to stay away (another source of interest when the official records appear). The second – more powerful – covers the wrenching anticlimax of Moscow competition, especially for Forrest, who, exhausted by months of pressure, botched the start of her 200 metre backstroke final to finish a devastating seventh. A few days later, the sixteen-year-old, back home on Sydney’s northern beaches, was wondering if it had all really happened.

This is an excellent insight into the athlete’s mind, and captures vividly the thrust and counter-thrust of the Moscow debate. Even if some figures become too one-dimensional, if athletes are indisputably right, if the debate is framed as too black or white, this book should be read. (It does not need the silly puff from David Marr, who sees it as ‘Cold War meets a kid from Cromer – and she wins’.) Lisa Forrest has gone on to an interesting and individual life after swimming; this book shows why and reflects the further insights she has gained. Above all, she demonstrates that sport is rarely divorced from the wider world, and always deserves serious attention.

Comments powered by CComment