- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Essay Collection

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Conformist gags

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

It is never a good moment at a party when, after one and a half drinks, the person you’re talking to pronounces herself ‘a little bit crazy’. You haven’t, as a rule, stumbled into the company of a psychopath; more probably, the opposite. The person who feels the need to claim craziness is nearly always the dullest, most conformist person in the room, and now you need to find a civil way of escaping her. Something similar obtains with self-attributions of a good sense of humour.

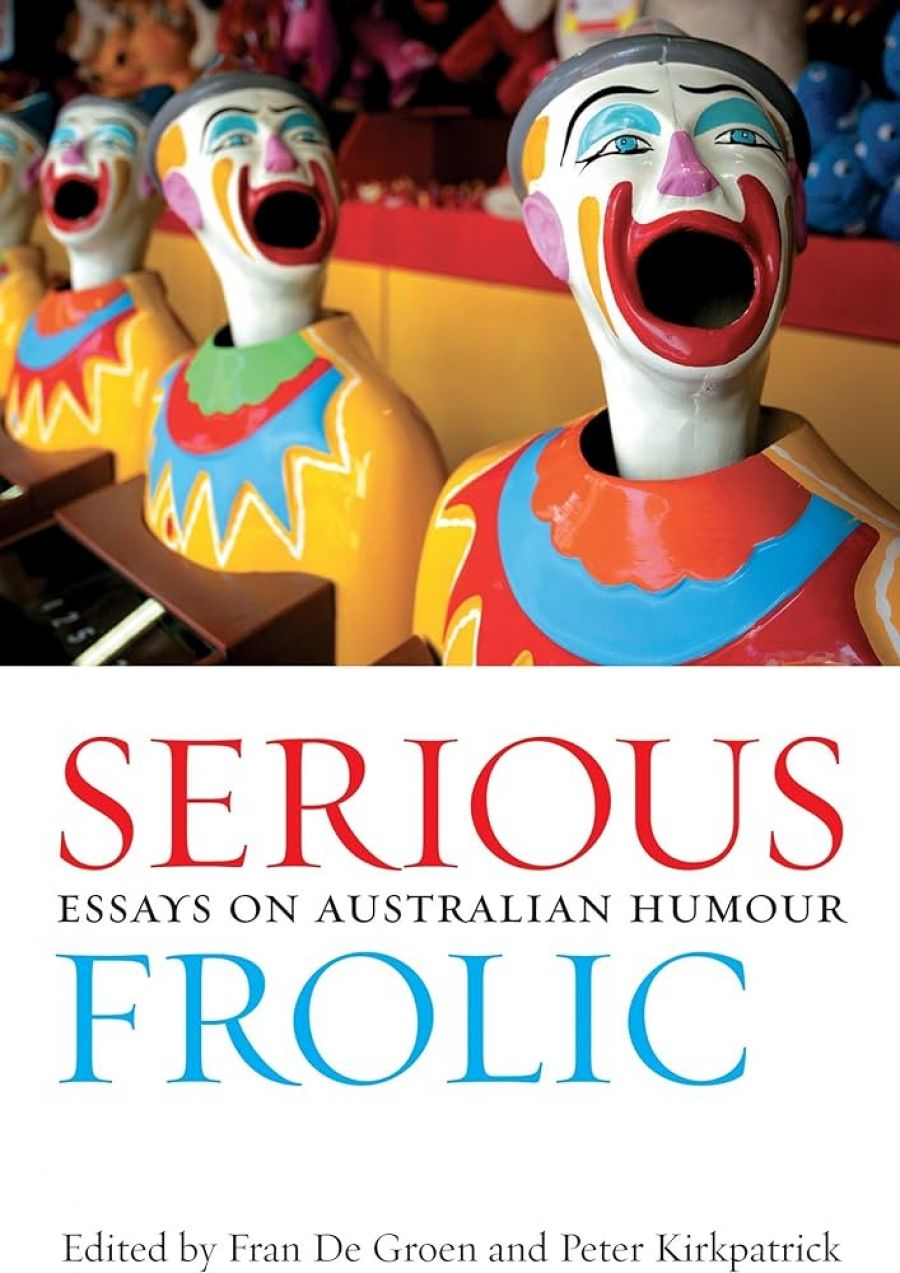

- Book 1 Title: Serious Frolic

- Book 1 Subtitle: Essays on Australian Humor

- Book 1 Biblio: UQP, $39.95 pb, 296 pp, 9780702236884

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Thus far the myth. The larrikin joker, lineal descendant of the wry bushman, is dear to us, but has plenty of contrary evidence to contend with. As Jessica Milner-Davis points out in the most provoking essay of this new collection, ‘mickey-taking’ is integral to the way Australians operate, culturally and interpersonally, but ‘mickey-taking against authority figures does not constitute serious, revolutionary challenge. Rather ... its licence is a condition imposed on acknowledgement and acceptance of the status quo.’ As if that isn’t irritating enough, Milner-Davis goes on to make the almost treasonous suggestion that ‘Australian humour seems to serve an aggressively normative and socialising function, to break a number of civilised conventions on obscenity and filth, and to underpin the egalitarian but conformist nature of Australian society’.

Milner-Davis’s affront is well worth addressing, because it explains a lot about how humour has worked in this country over the last couple of centuries. Serious Frolic, as a collection, takes the debate about Australian humour much further than it has ever been taken before, and way beyond the comfort zone of the self-congratulatory stereotype that tends to mark accounts of national humour. I have started with the displeasing proposition that humour serves Australian conformity, because humour’s broadly conservative role is one of the underlying themes of the collection. Licensed subversion is often celebrated in the various essays, but the licence to subvert one stereotype tends to come with a hidden fee of obedience to several others. While this is not inevitable, it is epidemic; many a good anti-racist joke is guilelessly sexist.

This is not really scandalous. Humour is a shared experience, a form of togetherness that marks the boundaries of the tribe, as well as questioning them. Laughter tends to feel like a simple and authentic experience, so we fondly imagine that it simply does good. As this collection demonstrates, it is much more complicated than that. Humour is a cohesive force and, when one starts talking about national cohesion, costs and benefits follow. No simple narrative of national cultural development (to maturity, cohesion, liberty, egality, whatever) can contain it. To look at Australian humour is to look at ourselves in mirrors that will not always flatter; it’s a lot like those mirrors at Luna Park.

Many of the essays included here take bearings from Ken Stewart’s classic analysis of Lawson’s ‘Loaded Dog’ as ‘Australia’s greatest bush nursery yarn’. The two leading dogs of the tale represent the poles of bush manliness: ‘The Loaded Dog is gregarious innocence, the epitome of idealized mateship; and his skulking adversary is brooding, selfish, and stand-offish bastardry.’ That the ideal mate comes witlessly bearing a substantial bomb bespeaks a sort of harsh sense of risk that recurs often in Serious Frolic.

The book is not an attempt to cover Australian humour systematically, for that is a sure way of making a complete fool of yourself. The essays address humorous literature particularly strongly (Lennie Lower studies, such as they were, are substantially increased by Peter Kirkpatrick’s and Michael Sharkey’s contributions, and I am certainly going to call up my library’s copy of Here’s Luck, 1930, from storage), cover some drama on stage and film, and make tactical sorties into cultural studies. Any fear that a glorifying account of the wry Bulletin bushman might overwhelm the project is put to sleep gently by Lillian Holt’s account of how Aboriginal people use humour as a survival technique in a society that gives them little objectively to laugh at. This is more an extension than a contradiction of the traditional whitefella self-image of laughing in the face of a dry and disappointing life, but it is an important one for all that.

Grim humour is a persistent thread in several essays, whether it be Holt’s Aboriginal humour, the sardonic humour that Frances De Groen traces in the diaries of POWs under the Japanese, or John McLaren’s account of Stan Cross’s great ‘Stop Laughing! This is Serious’ cartoon. Michael Wilding’s broadly (maybe even closely) autobiographical musings on his experiences as a writer of humorous fiction, and Virginia Blain’s contribution of a Hobart-Oxford angle to the ‘Ern Malley’ hoax, show just how personal things that are ‘just a joke’ can be. Whimsy in the service of developing cultural cohesion gets a run in Philip Butterss’s work on C.J. Dennis, Bruce Bennett’s on short fiction, Elizabeth Webby’s on early colonial literary parody, and Peter Pierce’s fantasia on the names of race horses.

A more confrontational note is struck in the section on performance. Anne Pender looks at the origin of Barry Humphries in the confrontation with 1950s Melbourne that set him, and stage satire, down a particularly raw trail. The limit of comic licence, questioned by Humphries from his Dada days onwards, is shown to be the abiding theme of Susan Lever’s account of Australian situation comedy on television. It becomes the explicit topic of John McCallum’s perceptive take on the constraints and taboos that stand-up comedians play with.

There is a canonising instinct at work in Serious Frolic, a sense of a corporate purpose in mapping Australian humour. However, even after a couple of centuries of European habitation on the continent, the result is necessarily partial and tentative. It says something about our scholarly culture that, in spite of being such a confessedly hilarious bunch of people, we have so little analysis of what makes us laugh. Of course, it is reasonable to fear the commedia dell’arte role of Dottore, the unintelligible expatiator who misses the point of the action before him. De Groen and Kirkpatrick are sensibly cautious about the risks of explaining the joke in their introduction. Still, the idea that analysing humour is some form of intellectual slumming seems perilously reminiscent of the cultural cringe against which Australian studies has always railed.

Consequently, Serious Frolic is actually a pioneering work of interdisciplinary scholarship that seeks to map the monuments of Australian humour and their significance. The story seems incomplete to me without direct attention to Jospeh Furphy’s great Such Is Life (1903) or to the political cartoonists, and others will have desiderata for the list. But that is the point of any canon – to frame an argument about what really matters, not to give the last word.

This is, perhaps, an overly literary first draft of the map; writing has only ever been one source for Australians’ appetite for the expression and consumption of humour, and is now hardly the dominant one. That will obviously need attention from other scholars. Also, the collection’s fairly general concern for the academic humanities’ trinity of race, class and gender can only tell part of the story. Humour is politically progressive only some of the time, and in some ways. It can be reactionary or libertarian; it can enforce or expose taboos; it can assert good morality, or not. Laughter can be intellectual sloth or express the most volatile mixture of motives. There is no reliable politics of humour.

Though it does not attempt to map every ethical and political option, De Groen and Kirkpatrick’s collection recognises this volatility in the purposes of Australian humour, and that is what makes it such a good foundation for a much longer discussion. The first thing it does is explode the nationalist myth that Australian humour is one homogeneous way of laughing. That we are one and we are many when we laugh is the right paradox to start with.

Comments powered by CComment