- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Australian History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: They're a weird mob

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Scheherazade, you have much to answer for! 1001 nights were fine for you, but by now there might well be that number of volumes offering that much advice about books, films and paintings, not to mention screen savers and blogs. So this bulky new book should be seen first, even primarily, as a marketing opportunity.

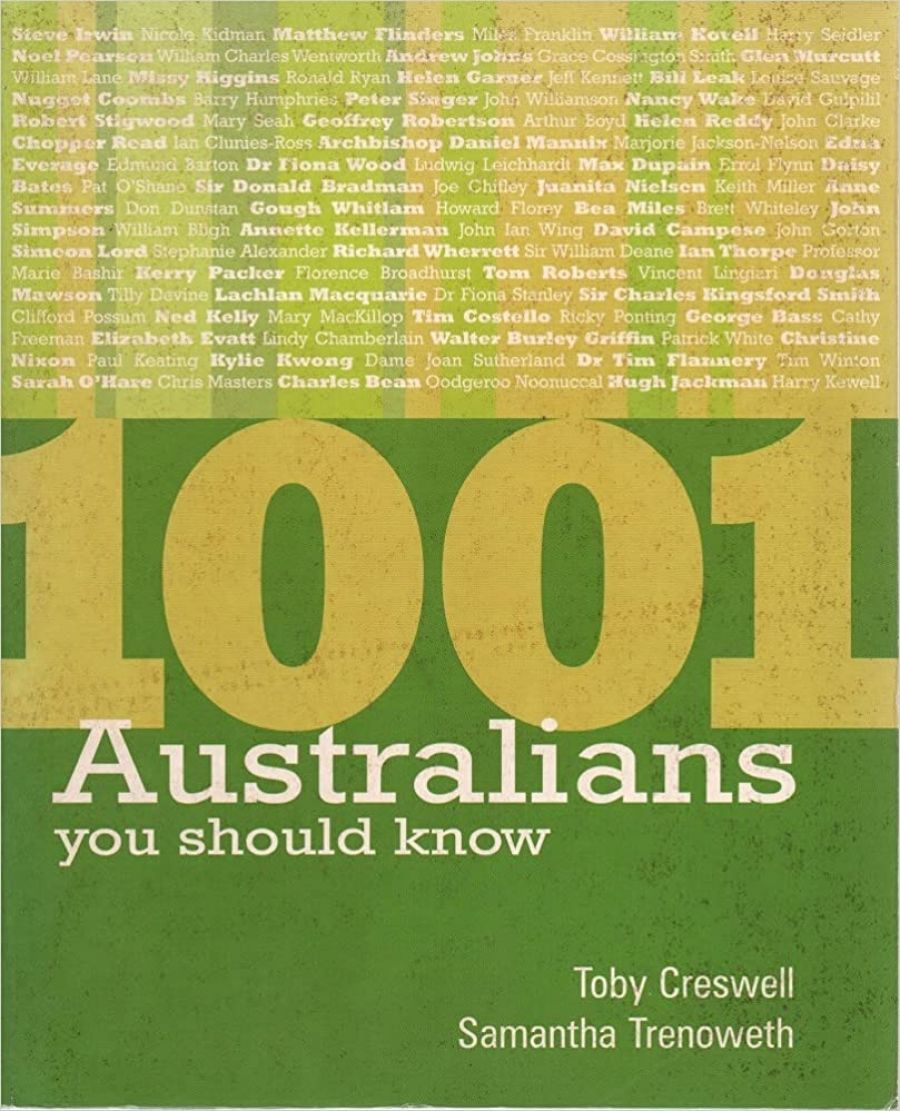

- Book 1 Title: 1001 Australians You Should Know

- Book 1 Biblio: Pluto Press, $49.95 pb, 741 pp, 1864033614

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.booktopia.com.au/1001-australians-you-should-know-toby-creswell/book/9781864033618.html

So what is the editors’ declared intent with their book? And why should I – or any reader – know these Australians? In the first paragraph of their introduction they refer to ‘interesting Australians’, but that is not per se a compelling reason to ‘know’ them. Then, quoting Paul Keating, they refer to people who ‘matter’. Pontius Pilate avoided answering his own question, ‘What is truth?’, but I must ask what that facile word ‘matter’ means. And to whom?

As a member of the New South Wales Working Party of the Australian Dictionary of Biography for more than eighteen years, I am very familiar with the disagreements that arise, even between real experts, about whether individuals should be included in such reference books. The arguments can be fierce, so I did not expect to agree with all of the current editors’ choices. After all, in these mean-spirited times, when we seek to exclude people – physically and culturally – if they are not considered ‘real’ Australians, it would be naïve to expect agreement about what (quoting the editors) ‘in totality sums up what it is to be an Australian’ and about those who should be excluded from a book like this.

Since one of Toby Creswell’s previous books was 1001 Songs (which allegedly celebrated ‘the defining musical form’, beginning with Gershwin and Dylan), fortunately he didn’t claim that they had to be heard before I die (something which would, doubtless, have hastened that event) – and since he was previously Australian editor of Rolling Stone, I should not be surprised by his skew-whiff choices in the ‘Arts and Popular Culture’ section. It is absurdly biased towards popular music and faux-celebrity. Frankly, I do not remotely accept that I (or any literate Australian who is likely to consult this book) should know or know about the likes of ‘Abigail’ (and I certainly do not consider that she warrants forty-three lines when John Brack, say, has only twenty-three), ‘Carlotta’ (sixty-two lines cf John Bell’s thirty), ‘Missy’ Higgins (who? with twenty-one), Stan Rofe (a disc jockey, apparently, whose entry is longer than Mem Fox’s) or a nonentity called Bec Cartwright. The impresario Robert Stigwood gets about as much space as Joan Sutherland and Jeffrey Smart put together, and certainly more than Sidney Nolan (who is, to judge from his allocation, about half as worth knowing as Kylie Minogue). The most blatant omissions include the renowned conductor Charles Mackerras and the Miles Franklin winner Thea Astley.

Given the editors’ clear prejudices, therefore, it hardly surprised me that this section is the longest in the book (226 pages of text), whereas ‘Faith, Charity and Cults’ (fourteen pages) is the shortest: we’re clearly a pragmatic, not to say prosaic, lot. It is reassuring, though, that the second-biggest section is ‘Politics, Public Service and Social Activism’ (140 pages) and not ‘Sport’, with eighty-six pages. ‘Science, Invention and Ideas’ gets half that, and (hardly a surprise given the hedonistic and self-regarding nation that we’ve become) there are twenty-four pages on ‘Fashion and Food’. Is the palindromic title 1001 properly understood in Roman numerals: MI? Enough fretting! How should I respond to what the editors have included? Is it reliable? Setting apart some typographical errors (was it all done in haste?), such as the misspelling of Dr Peter Hollingworth’s name (in an entry on the essentially invisible present governor-general, as Hollingworth doesn’t rate one for himself) and a reference (in Kamahl’s article) to Mat King Cole (no parentheses for King, either) and Paul Davies as ‘Davis’, there are other less excusable mistakes. Simply looking in their wallet would have told the editors that Catherine Spence is not the woman on the $5 note – that’s Betty Battenberg (aka Elizabeth Windsor). They give Max Harris the entire credit for founding Sun Books, and have remarkably little understanding of science and religion (leading to some risible claims about Daniel Mannix). They make quite a few dubious assertions – such as Julia Gillard being the preferred leader of the ALP. The book repeats the old fables about Colleen McCullough: in fact, she is not a graduate of Sydney University, nor was she a neuroscientist, but rather an EEG technician. Diligent editors investigate such claims. Their summary of Ben Chifley, who is surely one of our great prime ministers, is perplexing: ‘Chifley was a man of flaws [who isn’t?] and of great courage who had risen from poverty to a position where he gave the nation much of its character’; on the other hand, their opening sentences about Kim Beazley seem pretty astute: ‘Given the right break and a better than average campaign manager, Kim Beazley could still become the prime minister you have when you’re not having a Liberal prime minister … Beazley’s policies in areas like defence have always walked a fine line between conservative and startlingly so.’

As with the mob (a prime ministerial term and therefore concordant with our values) who consider themselves Australians, the characters in this book are a colourful, eccentric even opportunistic lot. They (the people as well as the entries) have to be approached with a certain scepticism, because they cannot always be taken at face value.

Comments powered by CComment