- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Review Article: Yes

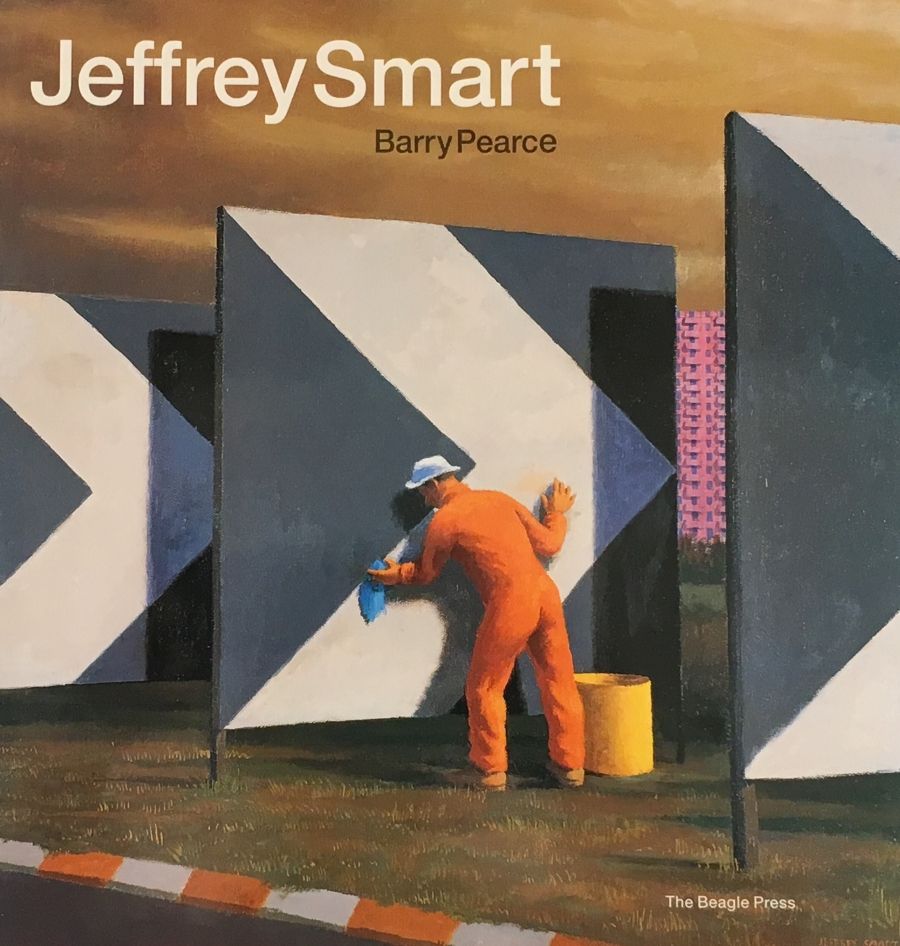

- Article Title: Making the familiar strange

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

This timely monograph presents the life and work of an artist whose paintings have altered the way we see the modern world, particularly the industrial landscapes fringing our cities. Jeffrey Smart’s intensely realised paintings have the effect of making the ‘familiar strange’. They force us to reconsider both our relation to and perception of man-made environments, dominated as they are by factories, apartment blocks, freeways and street signs. Smart’s paintings display a mastery of classical composition, light and perspective as well as revealing the artist’s ongoing concern with the interplay between realism and abstraction. The 252 plates included in this volume allow the reader to appreciate the development of Smart’s unique oeuvre over a period spanning more than sixty years. Accompanying these illustrations is a text by Australian modernist scholar and curator Barry Pearce. This provides a valuable addition to the existing literature on the artist.

- Book 1 Title: Jeffrey Smart

- Book 1 Biblio: Beagle Press, $120 hb, 256 pp, 0947349464

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Pearce felt that Peter Quartermaine’s Jeffrey Smart (1983) provided a ‘detached view’, while John McDonald’s Jeffrey Smart: Some Paintings of the 70’s and 80’s (1990) focused upon only part of the artist’s oeuvre. Smart’s own autobiography, Not Quite Straight: A Memoir (1996), he suggests, does not reveal many of the ‘secrets’ behind Smart’s paintings. In contrast, Pearce presents his own, personal biography of the artist to illuminate the meaning of the paintings. Drawing upon an impressive range of catalogue essays, letters and interviews, Pearce’s biography of Smart painstakingly follows the progress of the artist from his birth in Adelaide, to his final settlement in Tuscany. The first two chapters outline Smart’s childhood and early adulthood in Adelaide, tracing the influence of his teachers, friends and patrons. The artist was profoundly influenced by the work of his contemporary and friend, the overlooked painter Jacqueline Hick. Smart’s teachers – Dorrit Black, Marie Tuck, and Ivor Hele – also had an impact upon the artist’s work. These introductory chapters present a vivid, if at times over-detailed account of the Adelaide art scene and its peripheral position to the Australian art centres of Melbourne and Sydney.

Pearce notes the impact of books upon Smart’s development in this isolated environment. The artist monographs of John Piper and Paul Nash proved influential, as did the poetry and literature of a variety of authors, notably T.S. Eliot, who legitimised the city as a subject for Smart to paint, leading him to produce the paintings The Wasteland I and II (1945).

Chapter Three records Smart’s first trip overseas, including his visit to a Cézanne exhibition in Philadelphia, his time at Léger’s school in Paris, and his discovery of ‘Continental European culture’. Chapters Four and Five detail Smart’s twelve years in Sydney before his eventual return to Italy and Rome. Perceptively, Pearce notes that the postwar construction schemes undertaken in Rome made it an ideal environment for Smart to explore his fascination with industrial design. Chapter Six traces the artist’s discovery and restoration of the Tuscan villa Posticcia Nuova, his breakup with Ian Bent and his subsequent partnership with Ermes de Zan. The final chapter, aptly titled ‘composure and tranquillity’, paints an idyllic portrait of the artist as an old man achieving fame, fortune and success.

Pearce’s narrative follows the oft-repeated story of the ‘genius’ Australian modernist artist who escaped this country to further his creative talents overseas. In Pearce’s own words: ‘for the sake of both life and art it seems he [Smart] felt the need to break free from his Australian provinciality to find long-term love, respectability and become the best painter he could possibly be somewhere else. Posticcia Nuova has been a triumph!’ This concern with the lack of ‘culture’ in Australia is also found in biographical accounts of Nolan, Boyd and Tucker. One can’t help feeling that there are more revealing approaches to the lives and works of Australia’s modernist artists than this repetitious construction of Australia as an uncultivated backwater.

Pearce’s account assumes that biographical details about Smart will lead to a greater understanding of his paintings. At times, this approach is revealing. For example, the painting Corrugated Giaconda (1975–76) depicts a corrugated iron fence with a fading picture of the Mona Lisa pasted to it. To the left of this image is a heart containing the initials ‘JS, ED’. Pearce reveals that the poster symbolises Smart’s former lover Ian Bent, whilst the initials celebrate the artist’s love for Ermes de Zan.

At points, though, this insistence upon a literal connection between Smart’s enigmatic, timeless images and the artist’s own life are a little forced. Corrugated Giaconda can equally be inter-preted as a comment upon postmodernist appropriation and art in the age of mechanical reproduction. Surely the power of Smart’s famous The Cahill Expressway (1962) does not depend on whether ‘the fat man’ standing by the side of the massive development, ‘is Jeffrey Smart after all’. Indeed, its power depends upon the figure being an anonymous ‘everyman’. Pearce’s parallel between ‘the optical shimmer’ component of Papunya Tula paintings and the stripes of Smart’s 1960s compositions is also problematic. The Pupunya Tula art movement emerged almost a decade after Smart’s paintings of the 1960s, but there is no evidence to suggest that these artists were familiar with Smart’s work. Pearce’s parallel suggests that Pupunya Tula art can be understood within the same modernist cultural framework as Smart’s paintings. Yet Pupunya Tula art was the product of a unique cultural interplay between indigenous knowledge systems and the acrylic painting techniques introduced by the schoolteacher Geoffrey Bardon.

Nevertheless, Pearce does reveal some fascinating aspects to the artist’s work. He sees the timeless stillness found in Smart’s depiction of contemporary life as providing a link between the paintings of old masters such as Vermeer and that of modernist artists, including Nicholson, Balthus and Hopper.

Pearce identifies a key point in Smart’s development, when the artist realised that art could be ‘abstract but realistic with no relation to nineteenth-century painting’. This interplay between realism and abstraction led to some of Smart’s most powerful paintings. Works such as Trumper Park (1961) also provide an ironic comment upon the development of abstraction during the twentieth century. It depicts two lovers against the backdrop of a graffiti-covered wall encrusted with layer upon layer of peeling paint. Next to this are two classical stone gateposts through which one can see distant buildings and a playing field. By juxtaposing a Greenburgian flat wall against a distant, classical view, Smart directly challenges the authority of American abstract expressionism. Similarly, Housing Project no 84 (1970) can be read as a parody of minimalist art. The picture of the repetitive forms of the housing blocks looks at first like a minimalist sculpture, but, upon closer observation, one sees that Smart has included sensuous depths, lights and shadows.

Given the philosophical nature of Smart’s work, it is to be regretted that this major publication, perhaps the last one to come out during the artist’s lifetime, does not include essays that examine his work in greater depth. The enigmatic figures in Smart’s paintings invite speculation about the nature of our relationship with our environment. Pearce touches on the influence of literature upon the artist’s work and notes that Smart’s images are repeatedly used as cover illustrations for books, including Peter Carey’s The Fat Man in History. Yet Pearce does not explain the significance of the word OVID which appears upon a building in the background of Smart’s portrait of David Malouf. This makes direct reference to the author’s novel An Imaginary Life, in which the key protagonist is Ovid himself. Further, while Pearce recognises the significance of musical harmony and structure as an influence upon Smart’s paintings, this is not explored in depth. More could also be made of the uniquely individual path that Smart has steered between surrealism, realism, abstraction, postmodernism and installation art.

Nevertheless, the monograph provides a comprehensive introduction to Smart’s oeuvre. The biographical notes, list of exhibitions and bibliography at the back of the volume, coupled with the beautifully reproduced plates of Smart’s paintings, provide an invaluable reference for scholars and the general reader alike.

Comments powered by CComment