- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Politics

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Campaigning during the 1912 US presidential election, the great labour leader and socialist Eugene Debs used to tell his supporters that he could not lead them into the Promised Land because if they were trusting enough to be led in they would be trusting enough to be led out again. In other words, he was counselling his voters to resist the easy certitude that zealotry brings; to reject a politics that trades on blind faith rather than the critical power of reason.

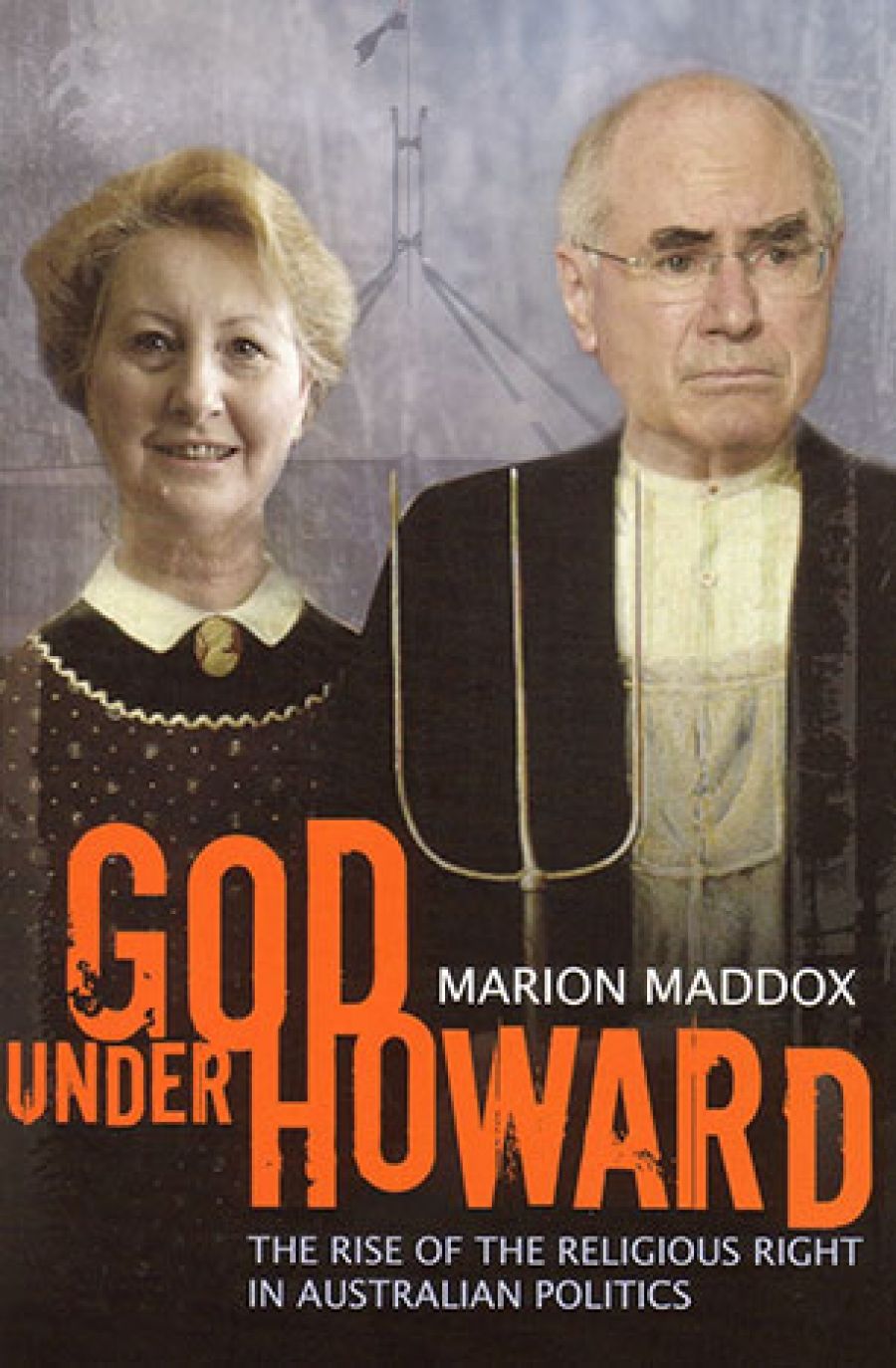

- Book 1 Title: God Under Howard

- Book 1 Subtitle: The rise of the religious right in Australian politics

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $29.95 pb, 386 pp, 1741145686

Similar fortitude does not exist in Australia, where religion is rarely thought to adhere to political debate. Our politicians are reticent to make public professions of their religious faith, and look uncomfortable doing so; ours is not a ‘confessional’ political culture but resolutely secular, which encourages the wide disjunction between the personal and the political, wary of the intrusion of a religious vocabulary. It seemed awkward, then, when Ross Cameron, the ex-federal member for Parramatta, publicly repented his adulterous ways: natural to the drama of Capitol Hill, perhaps, but alien to Australians unaccustomed to the political stage being used as a soapbox for the confession of sin. Similar anxiety greeted the surprising appearance of the evangelical Family First Party.

According to God under Howard, the infusion of Australian politics with US-style faith has been underway for some time. Marion Maddox, senior lecturer in religious studies at Victoria University, laments the lack of journalistic and scholarly attention to the intersection of politics and religion. An overlooked component of John Howard’s populist conservatism, Maddox argues, is an appropriation of fundamentalist techniques from the US right’s religious wing. While bending these techniques for a secular Australian setting, the deity Howard seeks to enshrine in Australian politics is the god of enterprise. While God under Howard contains much of interest, its thesis is ultimately unconvincing.

Maddox begins with an examination of John Howard’s religious and conservative self-presentation. Although he identifies formally as an Anglican, Howard’s childhood Methodist upbringing is usually cited as an explanation for his more dour characteristics: his colourlessness and lack of imagination. His meandering recollections of his childhood conjure a world of bright mornings, nuclear families, easy moral choices and spare honesty. Maddox, who herself grew up in a fervent Methodist household, demonstrates that Howard’s hymns to that 1950s world are a fabrication that do not reflect the Methodist way. Maddox’s upbringing involved the teachings of a church alive to the plight of refugees, scornful of racism, and active in the struggle for peace and disarmament; the eponymous weekly newspaper contained a breadth of commentary on social and political issues. Apparently, the Howard household preferred the comforts of Reader’s Digest and the Saturday Evening Post, the latter’s ‘Norman Rockwell cover paintings’ a pedestrian counterpoint to the anxieties of postwar Australia.

The invocation of a simpler world of church and stolid families toiling in a cloudless suburbia allows Howard to present a rigid pose against the idle cosmopolite. But his infamous comments in 1988 calling for restrictions on Asian immigration gave him pause about directly soliciting the fringe. Howard does not exhort the flock from the pulpit, preferring others to extol the hard-line viewpoint and spark the flint, stepping into the ensuing tumult to assert his calm authority, eager to flatten the tension yet dropping an approving wink towards the gilded fraternity to uncork the bottle further. This is a cynical exercise in triangulation that Howard has used often, a process of ‘cultivating others with a more extreme view than your own, making yourself look moderate by comparison’. But is this a technique Howard annexed from the US Christian right, as Maddox asserts, or the canny manipulation of the electorate by a man skilled in the uses of populism, chastened by his own political errors?

The tacit approval granted by Howard to the more extreme partisans of the Liberal Party, and the coded demonisation of those who resist the modest ‘common sense’ of the ‘Australian’ way of life coheres with the post-September 11 template of fear and moral endurance. As we are repeatedly instructed, perilous times are ahead and ‘our’ values are under threat: not only from fanatics who reject the foundations of our society but from the centrifugal tendencies that threaten to tear our traditions apart, including the postmodernists who throng our universities and schools, and who preach an insidious relativism. Howard used such an ambience to encourage a debate on public schools and whether they sufficiently instil traditional values. But the debate over values surely does not signify, as Maddox asserts, that US fundamentalism is taking hold in Australia’s soil. A similar dialogue is under way in France, for example, over the right of Muslims to wear religious dress in schools. A discussion of the limits of value pluralism, including the diversity of religious values, is surely a legitimate issue for Australia’s liberal democracy.

One of the strengths of Maddox’s book is her uncovering of the informal networks and lobby groups, from churches to think-tanks, that fuse the socially conservative safety of ‘Main Street’ to the unfettered capitalism of ‘Wall Street’. Maddox terms the Australian hybrid ‘Manildra Street’, an ungainly allusion to the street near where Howard grew up and to the name of the ethanol company of his friend and Liberal donor, Dick Honan. On Manildra Street, citizens frolic in the arcs of the market by day and return home to their nuclear families, swaddled in the certainties of a reassuring faith that promotes the theology of wealth. Ross Cameron draws sustenance from the parable in Matthew 20:2–16 (about the workers in the vineyard) in order to justify lower taxes; Brian Houston, a pastor at Sydney’s Hillsong Church, a congregation of the Assemblies of God (where Family First germinated), has written a book entitled You Need More Money.

Such vignettes make for absorbing reading; and Maddox’s chapter on the conservative exploitation of the electorate’s ignorance of Aboriginal religion during the Hindmarsh Island Bridge controversy is particularly persuasive. But on Maddox’s overwrought analysis, every political issue, if you shake it hard enough, disgorges a religious filigree. So John Hewson’s eventual downfall in 1993 is attributed to his tolerance of the Sydney Mardi Gras: an exercise in dubious revisionism at best. There is no evidence that Howard ‘sees political advantage in depicting his conservatism as religiously based’, and Maddox’s suggestion that a photograph of Howard exiting a church signifies that ‘on day one of his fourth term, Australia suddenly gained a faith-based prime ministership’ is a fanciful claim attractive only to conspiracy theorists. The more pressing danger to Australia is not the infusion of religion in our public life but the increasing loss of faith in the democratic processes on which we depend.

Comments powered by CComment