- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The Sydney poet Bruce Beaver died in February 2004 after a long struggle with kidney failure that kept him on dialysis for more than a decade. He was seventy-six years old. Beaver was seen as a sympathetic older figure by many poets of my generation, born a dozen years later. I met him when I was in my twenties, and found him to be a generous friend. When the poet Michael Dransfield, younger still, called on him in the early 1970s, it was a natural meeting of minds. In one poem in The Long Game and Other Poems, Beaver says that ‘poor Dransfield draped / me with a necklet of dandelions / once and kissed my forehead / in what must have been / a satirical salute’. I have a feeling that the salute was heartfelt, but Bruce was painfully modest.

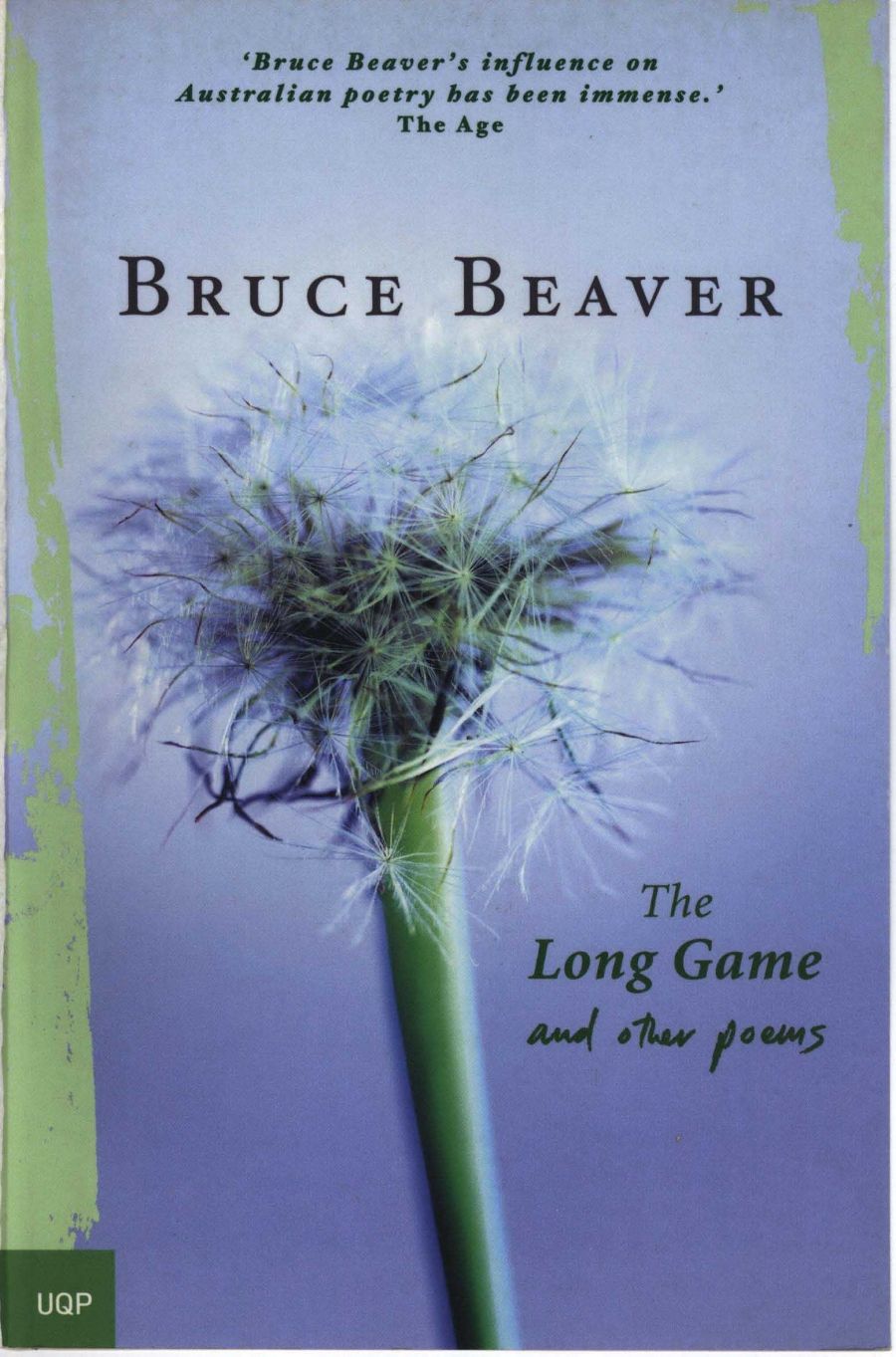

- Book 1 Title: The Long Game and Other Poems

- Book 1 Biblio: University of Queensland Press, $22.95 pb, 186 pp, 0702235091

As a reviewer, Beaver declined to review books he didn’t like. He seldom spoke critically about other writers, sometimes going out of his way to make excuses for lapses. When I interviewed him in 2003, I reminded him of his difficulties as a co-editor of Poetry Australia magazine during the 1970s, when an ambitious fellow-editor pushed him out of the limelight for many years. He said he had thought it was only a few months: ‘I couldn’t remember,’ he told me, ‘because I wanted to wipe it out of my mind.’

The first poem he wrote (as a teenager in 1947) was provoked by a radio programme on the bombing of Hiroshima. Beaver suffered a bout of severe depression around this time; the gift of verse and the curse of manic-depression following him in tandem throughout his life. His bipolar disorder, as it is called now, fitted him to follow the path pursued by Robert Lowell, who suffered from the same problem. Beaver knew that his illness allowed him – perhaps forced him – to experience life more intensely, and he simply put up with it.

This posthumously published collection was written over the last few years of Beaver’s life. It is a rich, ample and various book, full of the themes and issues that Beaver had celebrated and wrestled with for more than fifty years. The contemplation of human passion and folly is there, as it had been from his earliest writing, and the religious dimension of his thinking is stronger in this book, as befits the writer’s age. Bruce was in his mid-seventies when he put this manuscript together; he felt he was nearing the end.

One of his long-term consolations was music, with its deep emotional currents and its freedom from argument or rhetoric. He loved many kinds of music, from the popular songs of Rodgers and Hart to the moody complexity of Mahler. In the poem ‘End of Century Music’, he likens the music of Prokofiev, in a lovely conceit, to the taste of ‘a sweet lemon, although / the word sweet itself / cancels out his citrus otherness’.

There is quite a range of styles in The Long Game and Other Poems. Beaver occasionally echoes the polished Damascene effects of the early Kenneth Slessor, as in ‘Metamorphoses’: ‘Where bats like floating tambourines / Hold séances beneath the pines.’ Usually, though, his approach is loose, talkative, and philosophical at a very basic and human level. Sensual appetites are always hanging around, ready to mess things up. There are poems about Manly, the Sydney suburb where Beaver grew up and where he lived for most of his life. These colourful and critical sketches of the seaside were meditations on a theme that he returned to again and again, and his paeans to sun and surf, to tanned bodies and scattered litter, are, as always, a mixture of sensual celebration of nature’s forces of erosion and renewal, and anger and sometimes disgust at the way humans mistreat nature and each other: ‘The cliff is just an excuse for the bad taste / of estate agents and resident rock-dwellers.’

Beaver was conscious of his place in a long tradition of poetry. He mentions Basho and criticises his lack of compassion, and likens himself to the Chinese poet Po Chu-I (772–846). The position often taken up by the Tang poets – educated to a complex degree of erudition, exiled in many cases or unsuccessful, and often posing as simple hermits — was the role Beaver had gradually built for himself in his flat at Manly with his beloved wife and lifelong companion, Brenda. ‘Like Po Chu-I, I have been away from the Capital / for a long time ...’ he writes. Yet the Sydney CBD, of course, was a ferry ride away.

In technical terms, Beaver’s usual mode was a loose blank verse, the dominant twentieth-century fashion. In this book, he ventures further into the forest of technique. There are haikai, a ‘Kafka Senryu’, a group of ten sonnets in the middle of the book, and quite a lot of rhyme scattered throughout, including a rondeau redoublé, a complex French multi-rhymed form worked by Dorothy Parker and others, and employed here to jovial effect. The casual use of simple rhymes and occasionally naïve concepts reminds me of the sonnets of the late Edwin Denby, a much-loved avuncular presence to the younger poets who made up the second wave of the New York School in the 1970s. (Denby is featured in Jacket 21.) This recalls a poem by Beaver (in an earlier book, Letters to Live Poets, 1969) addressed to the New York poet Frank O’Hara, who had been killed in an accident on Fire Island in 1966, and who had been a friend of Denby’s.

The title poem is less successful, to me. A nine-page parable about children dancing around a secret magic tree, it is a peculiar adventure in rhyming couplets, and is subtitled ‘a poem about children’. It ends ‘Their laughter in the game rose high as any flame / consuming every woe, beyond all praise and blame. // With or without the sun it rose in joy upon / the long ecstatic dance, the circling marathon.’ Like the overwrought pagan epiphany towards the end of The Wind in the Willows, it left me feeling respectful, confused and slightly embarrassed.

But the best poems in this book are clear-eyed and vigorous. A lifetime of frank self-appraisal, careful observation and wide reading lie behind them. Though his personal manner was usually gentle, Bruce’s poems could rage against greed and war and waste: ‘... we will go on culling / civilian populations and trimming conscripted / and voluntary forces in limited wars with / criminal factions led by homicidal maniacs ...’

Beaver’s first collection of poems, Under the Bridge, was published in 1961, but the book that made his name (and that won three prestigious prizes) was his fourth, Letters to Live Poets, published in the midst of the war against North Vietnam. The act of making a poem is seen as a political choice, and is central to that book: ‘Writing to you,’ he says, addressing O’Hara, ‘sends the president parliament’s head on a platter; / writes Vietnam like a huge four-letter / word in blood and faeces on the walls / of government; reminds

me when / the intricate machine stalls / there’s a poet still living at this address.’

Sadly for all of us, that is no longer the case.

Comments powered by CComment