- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Custom Article Title: Brenda Niall reviews 'March' by Geraldine Brooks

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Spacious and solidly constructed, the classic nineteenth-century novel invites revisiting. Later writers reconfigure its well-known spaces, change the lighting, summon marginal figures to the centre. Most memorable, perhaps, is Jean Rhys’s Wide Sargasso Sea (1966), in which the first Mrs Rochester ...

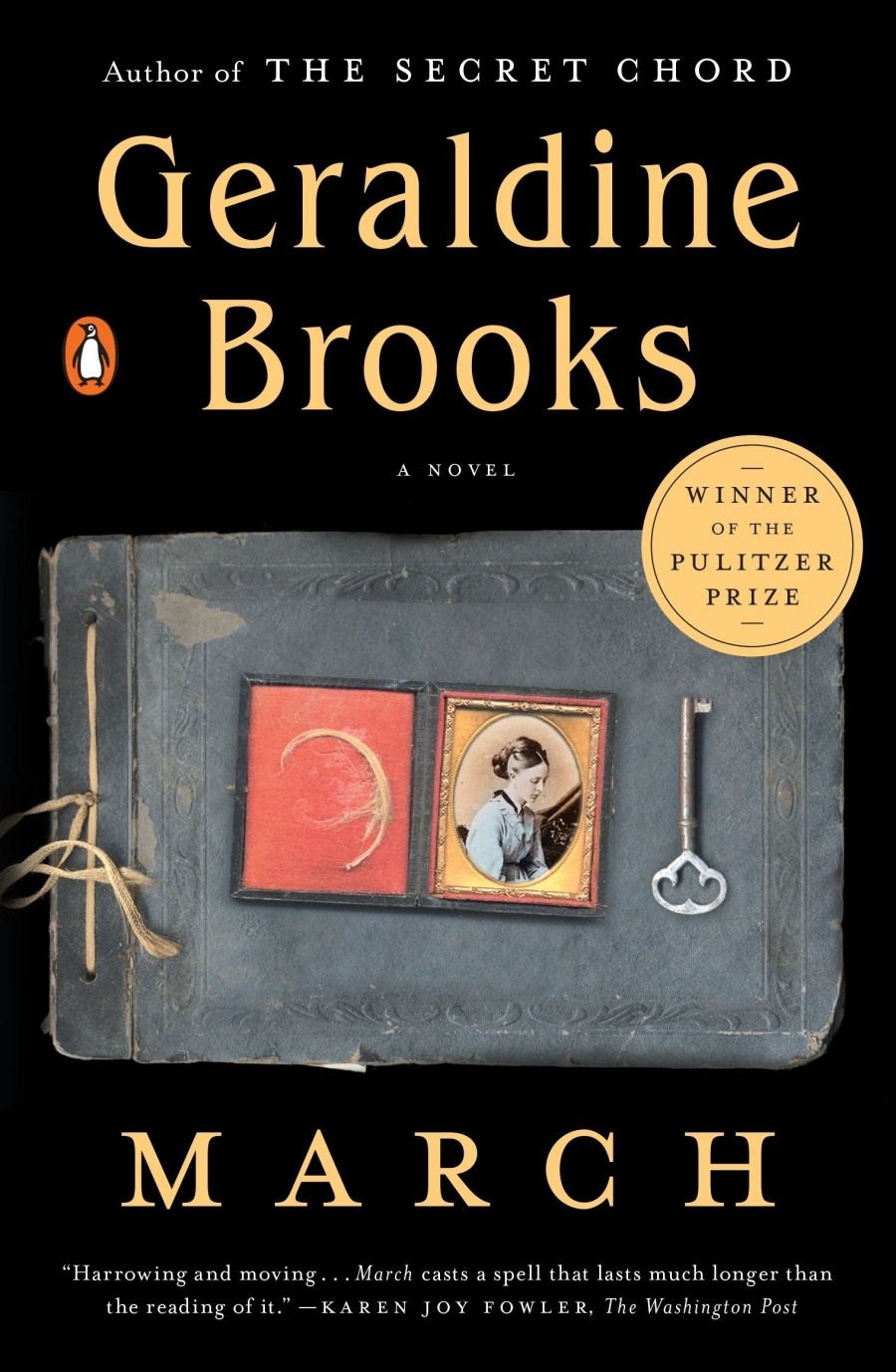

- Book 1 Title: March

- Book 1 Biblio: Fourth Estate, $29.95 pb, 352 pp, 0732278414

I doubt if any readers of Alcott’s novel thought much about the missing father. Away at the Civil War for almost the whole length of the novel, March is restored to his family just in time to add a Christmas blessing to the final tableau. Except for the fact that his absence means financial hardship for his wife and daughters, he is an irrelevancy in the plot; as a character, he scarcely exists. Yet it is Mr March who prompts Geraldine Brooks’s reworking of the family story. What did March see, Brooks asks, when he travelled south with the Union forces? What was the impact of war on the middle-aged husband and father from New England, whose conscience prompts him to volunteer his services as chaplain? Louisa May Alcott’s novel is silent on the issues of the war. The four daughters think that their father acts nobly in volunteering, but the questions of secession and slavery are not explored.

Filling the large gap in Little Women, Brooks has written a powerful novel about war and slavery. In her version, March is almost destroyed, physically and mentally, by witnessing the slaughter, by seeing the corrupting power of the slave system, and by having to confront a sexual transgression in his own past. His attempts to save lives, or even to give comfort to dying or mutilated men, are mostly futile.

Free to invent her own March, Geraldine Brooks has drawn on the history of Bronson Alcott, father of the author. A friend and associate of Emerson and Thoreau, Alcott was a social thinker and teacher whose attempts to put his ideals into practice failed utterly. Discussing her sources in an afterword, Brooks deals briskly with Alcott the reformer:

A vegetarian, he founded a commune, Fruitlands, so extreme in its Utopianism that members neither wore wool nor used animal manures, as both were considered property of the beasts from which they came. One reason the venture failed in its first winter was that when canker worms got into the apple crop, the nonviolent Fruitlanders refused to take measures to kill them.

Brooks makes March a more sympathetic character than the Bronson Alcott of history, whose diaries reveal a sanctimonious domestic tyrant. Although his abolitionist views were strongly held, Alcott was never tested as March is tested. Twenty years older than his fictional counterpart, Alcott did not go to war. It was his daughter Louisa who saw the cost of battle during a brief stint as a volunteer nurse in Washington.

Brooks invents March as a flawed idealist whose decision to volunteer has a strong element of selfishness. When he tries to atone for past mistakes by staying on in the South beyond any hope of being useful, his wife exposes his selfdramatising tendencies. As a study of a marriage under tension, March is subtle and eloquent. On fathers and daughters – surely a promising way to reread Little Women – it is less satisfying.

Told in the first person, mainly by March, but with four chapters from his wife’s viewpoint, the narrative voice is strongest in describing the landscapes of war, the battles and atrocities. Turning towards home, March’s sentimentality takes over. When ‘our little Mouse Beth’ is heard to ‘squeak’, today’s readers might well shudder.

March could stand in its own right as a Civil War novel, like Cold Mountain (1998). As in A Year of Wonders (2001), her story of an English village divided and doomed by plague in 1666, Brooks looks unflinchingly at horrors. March is built on some impressive research, including material on the precarious fate of the ‘contraband’ slaves – those caught between North and South after Lincoln’s edict had pronounced them free. I am not sure, however, that the appearance of Emerson and Thoreau in walk-on parts is worth the trouble. Bronson Alcott’s story would need a fuller account of the Transcendentalists, as well as a more astringent tone than that of March. Given that the novel departs radically from its origins in Little Women, it is also worth asking how much is gained by evoking the gentle domestic world of Meg, Jo, Beth, and Amy. Perhaps the real point is to show that in times of war there are no safe havens.

Comments powered by CComment