- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: ‘Let a message be found’

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In the opening pages of an early manuscript, ‘A Feast of Life’, Elizabeth Jolley ponders the question of whether a novel should have a message. She has no answer, but will write out of her ‘experiences and feelings’. If her writing does help anyone, then ‘let a message be found’, so that she might ‘feel that I am at least doing something in a wider sphere than the domestic routine within the walls of the little house’. Jolley goes on to describe her method: ‘I shall start in the early years of my life and try to make things take some sort of order but order is not a strong point with me and I shall write with all my heart so that there will be the noise of my children in these pages …’

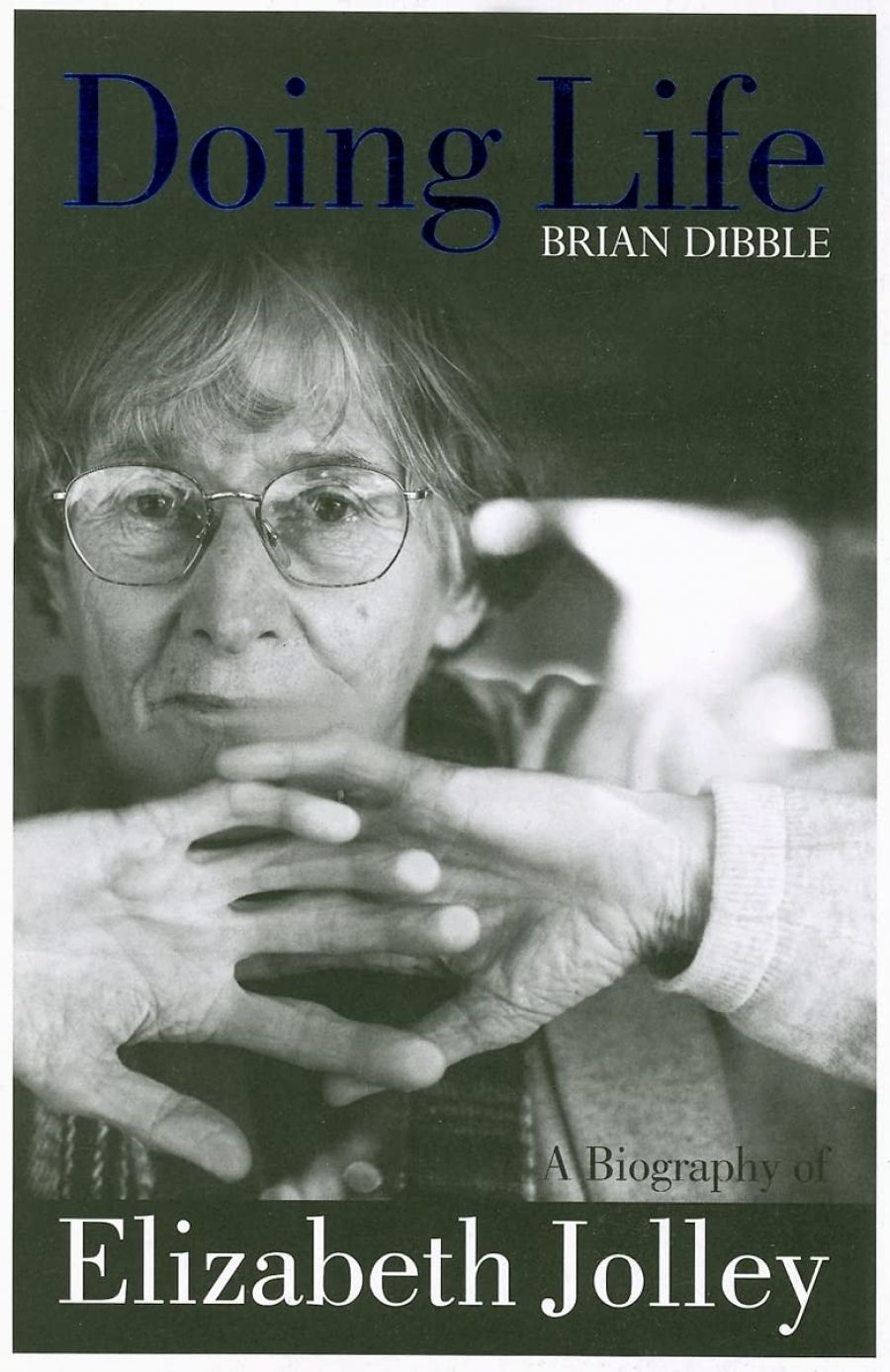

- Book 1 Title: Doing Life

- Book 1 Subtitle: A biography of Elizabeth Jolley

- Book 1 Biblio: UWAP, $34.95 pb, 350 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

However, Doing Life does amplify and inform Jolley’s work in always interesting ways. Finding out that there is a manuscript called ‘A Feast of Life’, that it was begun in 1956, when Jolley was thirty-two, worked on over several years, and finally recovered to provide the impulse for the novels of the trilogy (published between 1989 and 1994) which formed the pinnacle of Jolley’s writing career, is itself significant. Dibble has mined Jolley’s extraordinarily complicated writing and publishing history in ways that illuminate many questions about what preceded what, what became what, when what was started and how it evolved. For example, a novel later called Eleanor Page was begun in 1944, at a time when Jolley was in despair that she and Leonard Jolley would ever marry, and worked at over several decades. This manuscript of a ‘Nursing Home Place’, as she called it, is an essential precursor to Mr Scobie’s Riddle (1983), the novel with which she established that idiosyncratic comic voice, transforming what began, to use her own words, as ‘a lament … too painful to read’.

Jolley’s habit in her numerous essays, talks and interviews was always to reveal and conceal. Never duplicitous, she was at the same time an intensely complex woman. A fierce intelligence was overlaid by an equally sharp wit which in turn was kept in check by her placatory nature, truly gentle and kind, yet uncompromising and passionate.

Much of this complexity, as well as what has been much speculation over elements of Jolley’s life (questions about whether or not she was a lesbian were among the most misguided, and were dealt by her with disdain) is untangled in Doing Life, or at least given a structure. Although Jolley herself wisely realised, after her immensely long writing apprenticeship, that she should never strive for order in her writing, she did of course find her own, held in the systems of repetition with difference that distinguish all her work, which is often structured through memory and in which the chaos and pain of ordinary lives are modified by her comic sensibility. Dibble’s own ordering technique is to employ ‘layering’, placing what James Boswell called ‘scenes’ against one another. Interleaving these with a great deal of quotation, often by Jolley, focuses the detail as well as offering some lightness and variation.

Dibble had several of the biographer’s most essential tools, including time – more than a decade’s work has gone into the biography – and financial as well as research support. He also had privileged access to Jolley’s diaries and letters. While he was an intimate friend as well as a colleague of Jolley’s for many years, and had already written an unpublished biography of Elizabeth’s husband, Leonard, he manages this closeness by a well-judged objectivity. Early on, he invokes Hazel Rowley’s warning that a biographer must be ‘part historian, part detective and part novelist’, to which could be added the skills of an archivist, a psychiatrist, a literary critic and so on. This biographer clearly had that indefatigable energy for detection that biography requires, as the endless list of acknowledgements testify. Yet he has avoided the tedium of an overload of detail. And there are readings and commentaries on the various works which are illuminated by the biographical information Dibble brings to them.

Facing the inevitable problems of the selection and organisation of material, Dibble chooses to narrate this life more or less sequentially, beginning with Jolley’s parents and their antecedents, and in two major sections. The first, ‘The British Years’, is organised by way of the places where Jolley lived and worked; the second, ‘The Australian Years’, by the decades of her getting published and achieving success as a writer.

The historical background for this wide variety of contexts is useful, while the book draws on a sometimes bewildering amount of references. Visual material is one of biography’s greatest pleasures for me; Doing Life is beautifully illustrated. The cover image, of Jolley, is rather creepy, like the book’s title, and both are equally suggestive. Dibble constructs his narrative of Jolley’s life around the idea of the family, that most familiar and most fascinating of stories, one which is always the ground for Jolley’s fiction. The competing themes of the biography are those to which Jolley continually returns: emotional fulfilment on the one hand, made palpable through cherishing and deep friendship; and emotional deprivation on the other, held in the loneliness which haunts all her characters and the always present threat of homelessness, of being made the outsider.

The numerous family or familial environments that Jolley inhabited during her life – that of her original family, that of herself and Leonard; her Quaker boarding school, Sibford; the two hospitals in which she trained as a nurse; the two families that she, with her first child, lived with as a kind of ‘help’; the ‘progressive’ school she went to as matron and so on – all appear in different guises in the fiction. Each harboured tensions, and these became significant influences in Jolley’s writing. Jolley and her not much younger sister Madeleine were extremely close, and as children they happily shared a vivid imaginative life, but each of her parents was differently miserable. Her mother expressed her unhappiness in sometimes violent and unpredictable rages; her father in more repressed ways.

A source of confusion to the children was the presence in the family over twenty years of her mother’s ‘Friend’, Mr Berrington, who was also her father’s friend in another sense. This triangular relationship, with its tolerated tensions, was replicated later for a time in Jolley’s own adult life. Most significantly, perhaps, the house became a refuge during World War II for several German-speaking people who had fled from Europe. These intrusions were most unwelcome to the children, but the extreme sorrow and often extraordinary demands of these people haunted Jolley’s life. So too did the suffering she witnessed in her hospital training, especially that of the twisted bodies of children in her first, orthopaedic hospital, and the thousands of terribly wounded and often dying soldiers who flooded into the second.

One of the notable things about this remarkable life is Jolley’s capacity for incredibly hard work. The steely resolve she displayed in her determination to be a published writer, during all those decades marked by innumerable rejections, rewritings and trying out different genres and styles, was matched by her never skimping on anything. In her capacities as keeper of her own house, wife and mother, nurse to her husband as his arthritis gradually incapacitated him, through several part-time teaching jobs, as the ‘weekend farmer’ on the small holding she loved at Woorooloo, in her many friendships and acquaintanceships: Jolley always attended to each particular task.

She was often daunted, sometimes angered and usually exhausted by the demands of that life. But she continued to write and, when she began to be widely published, to accede to, indeed relish, all the appearances required of contemporary writers. She never wrote until the house was quiet and all the work was done, late at night. When this became too difficult, she wrote in the early morning hours. She always carried a notebook, and her habit of making ‘the quick note’ was learnt early and became invaluable. Her fiction has just that quality, of a mosaic, of fragments knitted together.

When she was attempting to write a biography of her sister shortly after Vanessa’s marriage to Clive Bell, Virginia Woolf lamented to her new brother-in-law that she was both ‘too near, and too far … and I ask myself why write at all? Seeing I never shall recapture what you have, by your side, this minute.’ This is the dilemma of biography; a Life can never be the life; words on the page are unable to achieve a return of the Elizabeth I knew, who is of course different from the person others knew. The multiple possibilities of her life are however captured, in some sense, in the range of names by which she was known at different times. Born Monica Elizabeth Knight, she changed her name to Fielding (not a random choice) as a young woman, then to Jolley; she was always called ‘Bunty’ or ‘Bunti’ in her immediate family and by close family friends, often ‘Beaky’ at school, ‘Knight’ in the hospitals, later ‘Fish’ by her husband, and she became famous to a reading public as Elizabeth Jolley.

Nevertheless, her hard-won achievement, the legacy she wished for – as a child and young woman, Jolley prayed that she might become a writer – is her inimitable writing, and this biography achieves a great deal. Properly circumspect, indeed scholarly (with an invaluable index and an extensive bibliography), Doing Life is enormously informative. It gives that writing a background, one that increases our understanding of it as well as of those myriad impulses from which it was generated.

Comments powered by CComment