- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

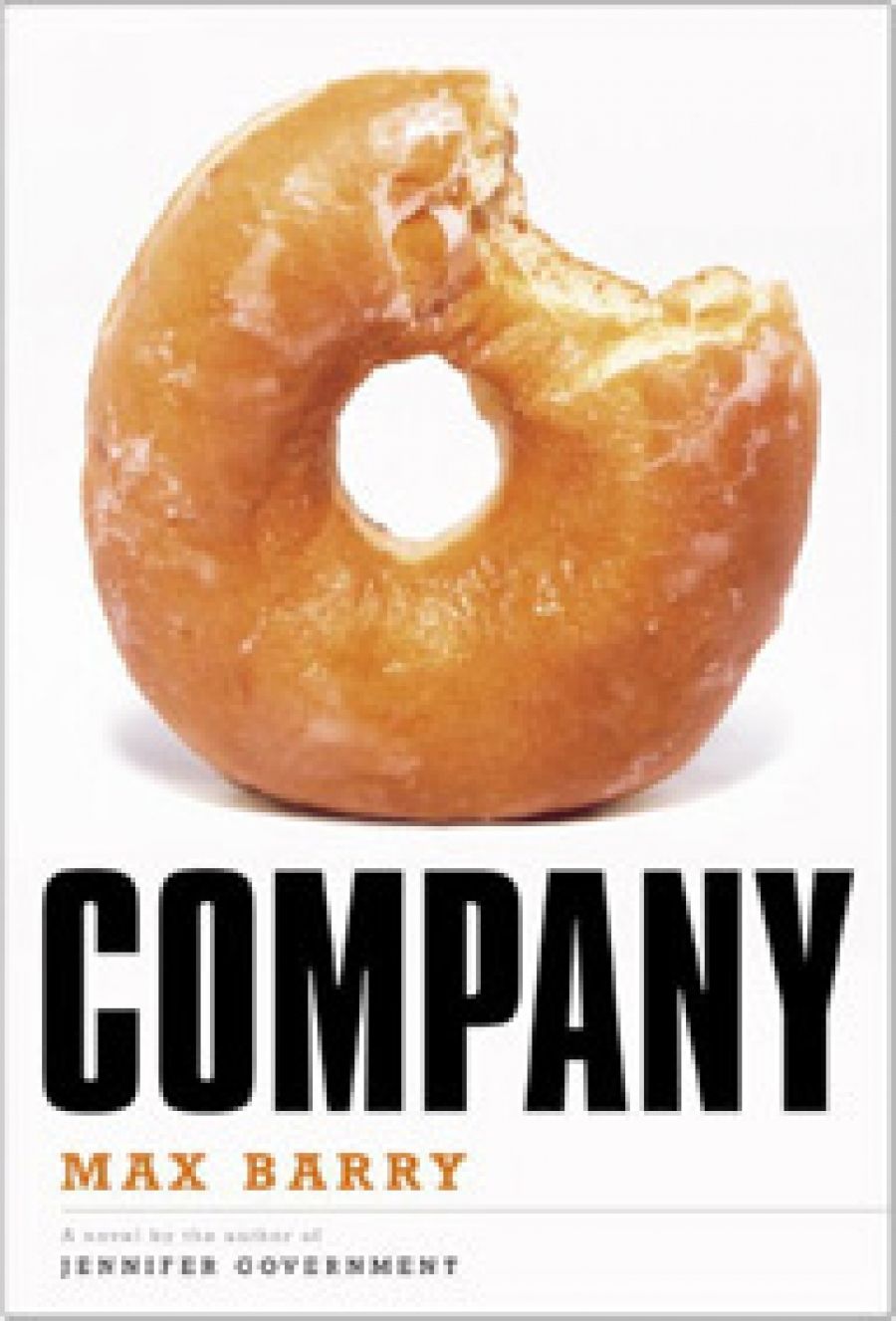

- Article Title: The missing doughnut

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Australian author Max Barry specialises in satirising the profit-obsessed world of corporate enterprise in his sharply observed, easily digestible novels, of which Company is his third. Syrup, his first book, published in 1999, told the story of Scat, a character whose name more than broadly hinted at the author’s jaundiced view of the career he had previously been engaged in (Barry was a salesman for Hewlett-Packard while he was writing the novel). A venomous satire about corporate rivalry and marketing squarely aimed at Coca-Cola, Syrup was also an easily marketable product. Thanks to the American branch of Penguin Books’ interest in the manuscript, Syrup established Barry as that classic Australian success story, the artist who was better known overseas than in his own country.

- Book 1 Title: Company

- Book 1 Biblio: Scribe, $29.95 pb, 352 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.booktopia.com.au/company-max-barry/book/9781921215643.html

Barry’s second novel, Jennifer Government (2003), was set in a near future where corporate dominance had become so complete that people took their names from the companies that employed them. It featured a plot involving murder as the ultimate marketing campaign. As with Jennifer Government, Barry’s new novel adds an unexpected dollop of science fiction to his widdershins spin on corporate culture. Similarly, and reminiscent of the fact that George Clooney’s production company snapped up the rights to Jennifer Government before publication, the sparse prose and rapidly moving plot of Company suggest a book written with film adaptation in mind.

Barry’s latest protagonist, Stephen Jones, is a fresh-faced employee starting out at Zephyr Holdings Incorporated. Being a new staffer, Jones is unaware of company protocol. Within a short span of time, not only has he walked unannounced into the office of his manager, to the stupefaction of his fellow staff, but Jones has begun to question what exactly it is that Zephyr Holdings Incorporated does. According to the company’s mission statement, Zephyr ‘aims to build and consolidate leadership positions in its chosen markets, forging profitable growth opportunities by developing strong relationships between internal and external business units and coordinating a strategic, consolidated approach to achieve maximum returns for its stakeholders’. Such pitch-perfect evocation of corporate babble proves that Barry is an insightful and observant writer, a belief supported by his cast of characters, who variously battle with voice-mail, assign subordinate staff to trace missing doughnuts, struggle with the resident office psychopath, and fall hopelessly in love with their clients. Given that they are sales representatives, however, such behaviour is considered virtually normal in their particular department, for, as Barry dryly observes, ‘There is something wrong with the kind of person who becomes a sales rep, or if not, there is something wrong after six months.’

Unfortunately, as observed by British critic Kim Newman of Jennifer Government, there is something equally wrong with Barry’s characters, who seem ‘off the shelf’. Despite being swiftly and wittily sketched, as personalities they are too often slight, lacking in depth and character development. As typified by the sex-symbol receptionist Eve Jantiss, who, the author describes, ‘looks as if she is just stopping off at Zephyr on her way to an exclusive nightclub opening’, they are little more than caricatures, and depend on the author’s quick wit to animate them.

This lack of depth extends to the narrative of Company, which, despite being very funny in several places, unfortunately reveals itself to be as intellectually unsatisfying as a missing doughnut (the plot’s central McGuffin) is nutritional.

Despite sounding damning, however, this is by no means a dismissal of Barry’s literary prowess. Like the late Douglas Adams, author of The Hitchhikers’ Guide to the Galaxy (1978) and its numerous sequels, Barry has an astute eye for the absurd, and an equally incisive ear for a deft and delightful turn of phrase. Like Adams, his fast-paced humour sometimes overtakes his plot, resulting, in this case, in a climax that necessitates a suspension of disbelief in order to accept the sequence of events that Barry has constructed. Speaking of his apparent obsession with writing about the world of global business in 2006, Barry said, ‘I find corporations so intriguing that I have no trouble writing about them. I mean, come on. Corporations! It’s like there are these gigantic monsters living among us, and we don’t mind that they’re monsters because when we look at them they smile and hand us cheeseburgers.’

In the case of Company, Barry hands us an easily digestible novel, which, like a multinational burger, briefly satisfies but leaves us hungry for more substantial fare.

Comments powered by CComment