- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Young Adult Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Redeeming Tom

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Not really? Tom Mackee? That boorish, pervy, smart-mouthed Year Eleven boy from Saving Francesca (2004), who offended Tara Finke whenever he opened his mouth, is the central character in Melina Marchetta’s new book. At least he loved music and was not a bad guitarist. Last time we met him, Tom became part of Francesca’s circle at school. Occasionally charming, a dab hand at witty repartee, he was falling for activist and feminist Tara Finke. Now he’s not sixteen anymore, but twenty-one (or thereabouts).

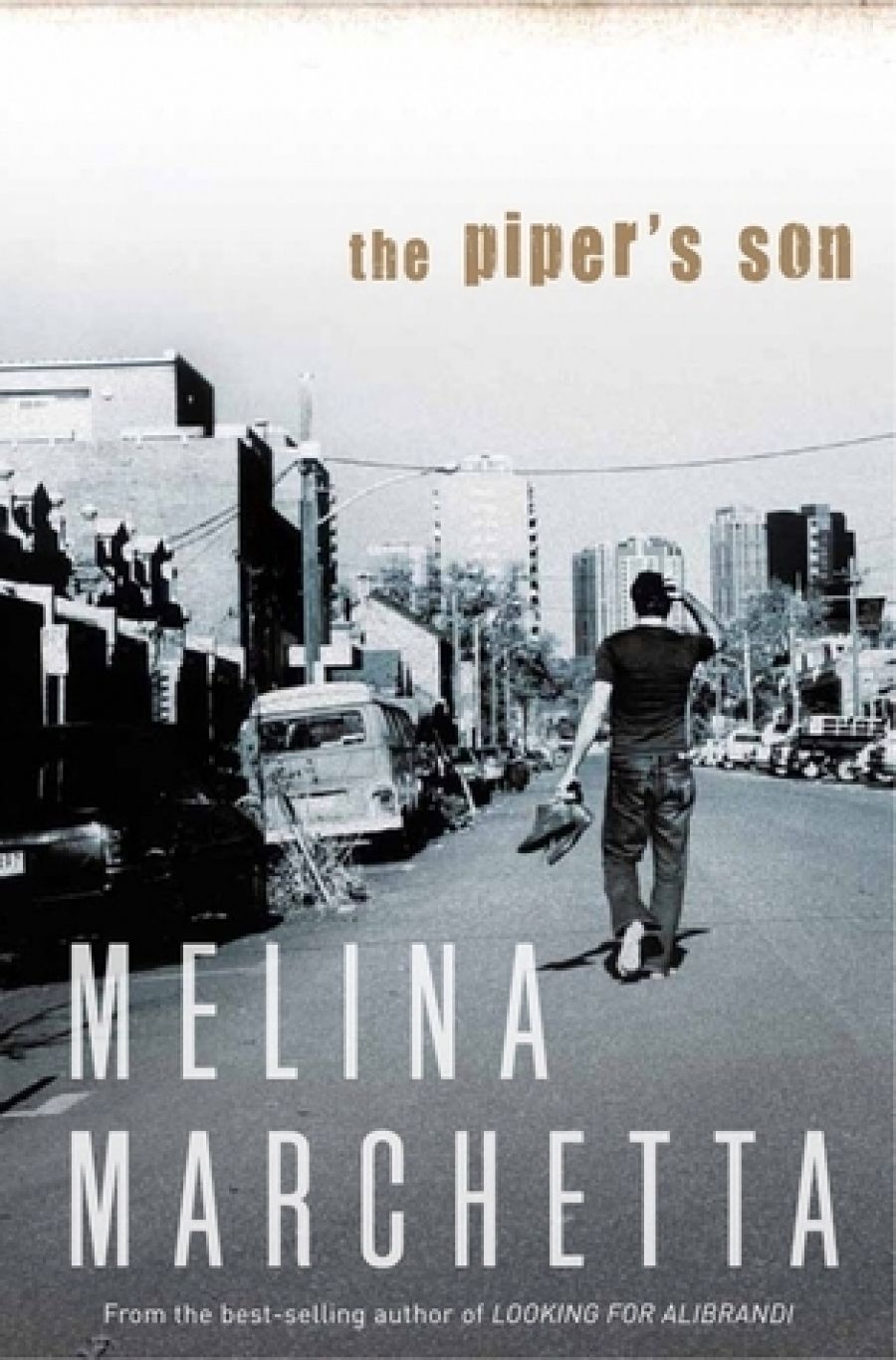

- Book 1 Title: The Piper’s Son

- Book 1 Biblio: Viking, $24.95 pb, 328 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

The intervening five years have been tough for Tom and his family. Grief and sadness have overwhelmed them. Two years ago Tom’s beloved uncle, Joe, younger stepbrother of his father, Dominic, was killed in the London subway bombings. There was no body to lay to rest, as with Tom’s grand-father, who died at Long Khanh forty years earlier. Dominic’s drinking has driven Tom’s mother and much-loved younger sister, Annabel, from Sydney to Brisbane. Tom refuses to forgive the man who was once his hero, ‘the piper’. Full of anger and latent violence, Tom has dropped out of university, alienated his old friends and been unforgivably awful to Tara, whom he loves. He has replaced his old group of supportive friends with useless flatmates, and numbs his grief and anger with alcohol, drugs and casual sex.

As the book opens, Tom, stoned, has smashed his head in a fall; his flatmates have fled. His father’s twin sister, Georgie, takes him in on the condition that he will eschew drugs and get a job. To repay the money that his former flatmates stole when they were employees, Tom works gratis at the hotel owned by Justine’s uncle.

The narrative is told alternately from Tom and Georgie’s perspectives. Forty-two-year-old Georgie has her own demons: grief has lead to bouts of depression; now, she is unhappily pregnant to her ex-partner. He has a six-year-old son from a brief relationship which took place after Georgie suggested a temporary break in theirs. She refuses to acknowledge the pregnancy to anyone, silently daring them to mention it.

Tom’s self-loathing and self-destructiveness are initially exasperating, but we can discern signs of redemption. His journey back to himself is gradual, tough and, thankfully, without a magical epiphany. While the narrative is not especially addressed to young adults, there are definite coming-of-age themes as Tom saves himself by realising that he can help to heal his fractured family.

Tom’s ‘rite-of-passage’ is to move from seeing himself as the centre of the universe. He begins to understand people and their motives, rather than making assumptions about them. This is potently shown in his racist reaction to a fellow worker, Mohsin, whom he calls ‘Mohsin the Ignorer’. We soon discover that Mohsin was deafened in a childhood accident, and has not been deliberately ignoring Tom. By the end of the book, they plan to share a flat.

Beneath the surface run ideas about the destructiveness of mothers and daughters who harbour long-held resentments, and about father–son relationships inhibited because of conventional notions of masculine behaviour. This theme is further explored through the competitiveness between the young men.

While the novel’s subject material – the messiness and sadness of life – suggests a dark tone, Marchetta’s narrative is imbued with wit and a wickedly sardonic view of the world. For instance, when Georgie contemplates how to keep her breastfed child safe from foetal alcohol syndrome, cot death, drowning in backyard pools, airbags, peanuts, internet predators, terrorists and natural disasters, she is driven to a damaging glass of wine and a cigarette.

In The Piper’s Son, Marchetta is doing what she does so well: showing us that although the Finch Mackee clan’s lives are sorrowful and in disarray, the connectedness of people, the strengths of friendship, the bonds of family, laughter, the sense of community in an Italo-Catholic-Polish-Chinese-Australian pocket of inner Sydney, and the power of forgiveness are sustaining. She expresses this in tense, frank, revealing, playful, witty dialogue and emails. People reveal themselves to us so frankly it is sometimes painful, as though the reader is intruding, but the exchanges are also frequently hilarious, such as when Georgie’s friends, at a café, prevent her from eating and drinking inappropriately, without mentioning the reason why. The book is not just about ‘feelings’; there is plenty of physicality, from the healing balm of a hug, to more erotic encounters. Yes, the ending has reconciliation and romance, but the pitch-perfect dialogue saves it from sentimentality.

Another pleasure is the background soundtrack: the music and lyrics that Justine and Francesca write and play, helped or subverted by Tom and Ned (who hates rhyme); and the songs Tom listens to, tracks that he shared with Joe, from Lyle Lovett to The Cure, The Clash, The Waterboys, Joe Satriani and Regina Spektor.

It is not essential to have read Saving Francesca to enjoy The Piper’s Son, but the new book will remind readers how sharp and surprising Marchetta’s writing was in the preceding two books of her ‘inner-west trilogy’ – the other being her first, Looking for Alibrandi (1992).

Marchetta has collected awards for her previous books, including the prestigious Michael J. Printz Award in 2009 – and with good reason. The Piper’s Son is quietly funny, insightful and resonant.

Comments powered by CComment