- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The way of the world

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

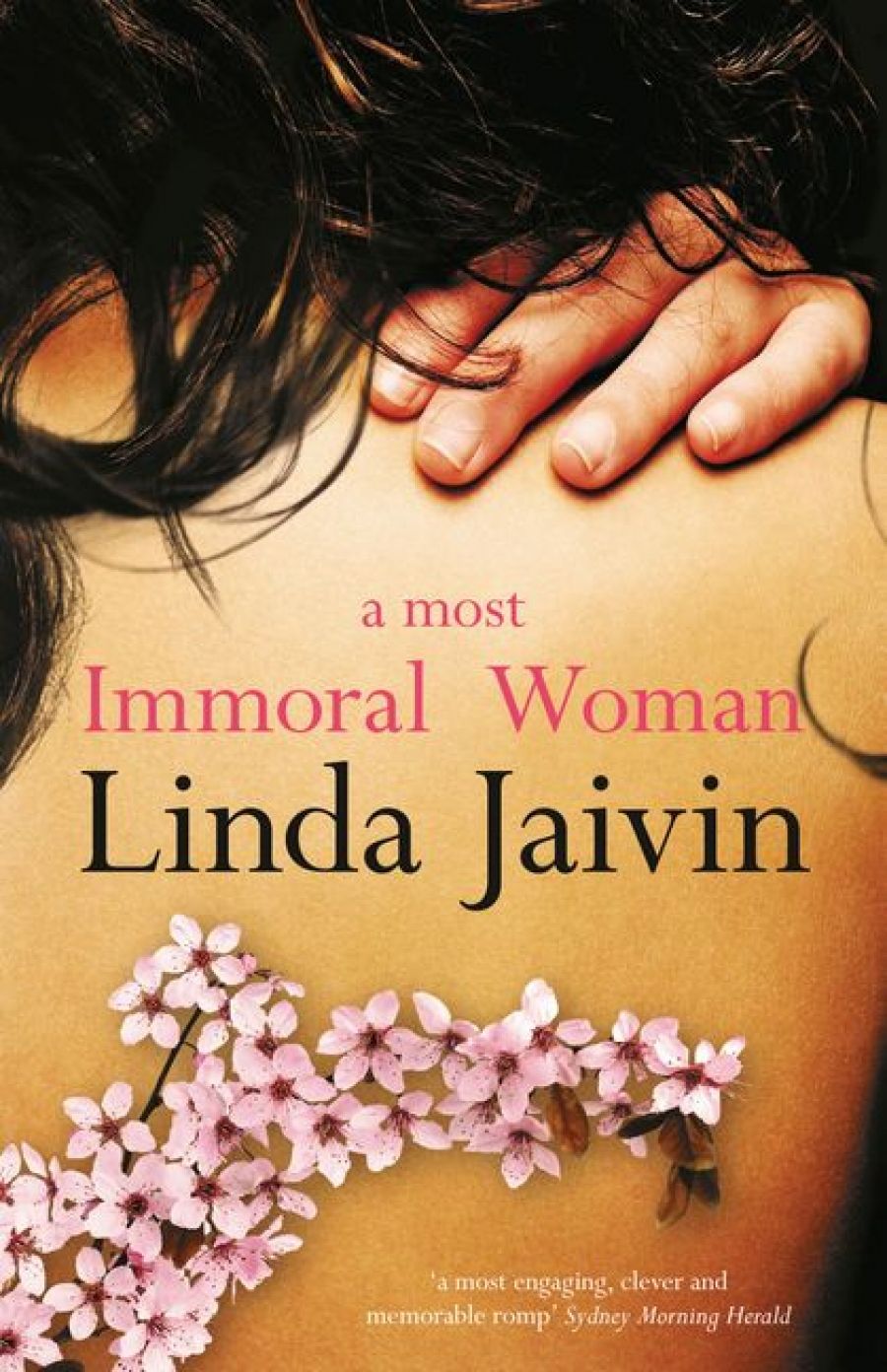

Rarely does an image on a novel’s cover appear exactly as you, the reader, imagine the character to look. But Mae Ruth Perkins, on the elegant scarlet cover of Linda Jaivin’s new novel, definitely does. Bordello eyes, boudoir lips and all: the face in an early 1900s photograph is Mae’s own. The jewellery, faintly visible, is hers too, just as Jaivin describes it: ‘He helped her tie a black ribbon with a silver horseshoe charm around her neck, the open part facing upwards … She asked him to fasten a delicate platinum chain with a vertical triplet of gold hearts around her neck as well.’

- Book 1 Title: A Most Immoral Woman

- Book 1 Biblio: Fourth Estate, $39.99 pb, 370 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

‘He’ is George Ernest Morrison, the famous Australian ‘Morrison of China’: the Melbourne doctor turned correspondent who by 1904 is widely admired, particularly for his dispatches during the Siege of Peking in 1900 to TheTimes, which has prematurely reported his death. But he is approaching (what was not then called) a mid-life crisis. She is the pampered, idle, twenty-something daughter of a rich Californian senator, who has come to China to escape scandal, or to create it. Mae, one of Morrison’s male friends warns him at the start, is trouble. And so it proves, for those gold trophies she wears represent only three of her many amorous conquests, and she intends to ‘amuse herself’ by making more.

Each of Jaivin’s novels and non-fiction books has been steeped, the profundity varying, in China and sex. Based on fact, this new novel is her most skilful combination so far of scholarship, research, invention and what she calls ‘playfulness’. An experienced practitioner of all four, Jaivin can invent a lovesick screed that Morrison writes to Mae in his cabin and then throws overboard; just as readily, she works into his conversation with a couple of China-hating missionaries a literal quote from his journal: ‘Whilst I confess I came to China possessed of the strong racial antipathy towards the Chinese common to my countrymen, that feeling has long since given way to one of lively sympathy, even gratitude.’ Later, comparing Japan and China, Jaivin observes that they represent the control freak and the ‘cunt-struck’ (Mae likes the word) in Morrison:

Japan had a way of coolly excluding the foreigner that China, for all its violent spasms of xenophobia, had never mastered. If China’s government did not command Morrison’s respect as Japan’s did, China as a nation had won his love. For a man who craved order, who spent much of his time collecting, cataloguing and recording, Morrison had a weakness for the garrulous, the passionate, the chaotic, the unpredictable. China. Mae.

The thread of comparison between Britain’s plucky little ally, Japan, and its corrupted opium-addicted client, China, provides the line on which the narrative’s dirty linen is hung. The two gradually change places on the high moral ground. Republicans emerge, seeking to reawaken China, while Japan’s oppression of Korea expands into aggression against Manchuria. But Morrison continues to support the Japanese, even though they won’t let him report on the war. ‘If the war is as righteous as you claim,’ Mae asks him, ‘then why are the Japanese so reluctant to be observed in the practice of it?’ A good question, even today.

Even as the narrative, veil by veil, reveals Mae for what she is, Morrison’s public image is also progressively stripped bare. Traditionally revered for his energetic north–south marches, his judicious journalism and his rejection of ignorant China-haters, the great G.E. emerges here as a self-doubting, indecisive, vindictive, parsimonious, vain, status-conscious, British-Australian hypochondriac, who is judgmental of others, their teeth included. When he compares Mae’s ‘fathomless eyes’ to a pool where ‘we kneel, only to fall in love with our own reflections’, even in his euphemism he reveals his narcissism.

All the men Mae leads astray have had affairs, and after her they waste no time in having more. Morrison is at first pleased to find that she doesn’t kiss like a virgin. But when Mae tells him about her lovers, he labels her ‘a nympho-maniac of the highest order’, and is soon looking around for a substitute, with no sense of hypocrisy. Men, Mae observes pithily, ‘seem far more tested by the morality of a woman than they do about the morality of war’. The double standard is eternal, Morrison’s fellow journalist and arch-rival, Martin Egan, declaring: ‘Men always set the rules. It’s the way of the world.’

But this is a new century, Mae tells them: she will not be caged, and marriage won’t suit her. In the end, Mae marries neither of them, and afterwards they all marry others. Given Egan’s chauvinism, his marriage in 1905 to the young feminist Eleanor Franklin – who has made a pitch for Morrison – seems rather out of character. So does Mae’s marriage, a decade later, to an Oakland developer.

It is not to detract from Jaivin’s achievement in this witty, entrancing book to note a few glitches. In Japan, people wear geta, not geita; they commit seppuku, not seppuko; and the novelist Jack London would surely have embarked not from Tokyo but from the deep-water port of Yokohama, thereby affecting the plot. In French, lui should be le, and perdus needs to lose the s. But in Jaivin’s capacity to bring Mae and Morrison to life in the China of 1904, whose real back streets you can see, hear, feel and smell, she now rivals Brian Castro. Her next venture, a Chinese/English opera, will be something to see.

Comments powered by CComment