- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Glimpses of Masoko

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Ben Hills’s biography of Princess Masako has a second subtitle: The Tragic True Story of Japan’s Crown Princess. It is a taste of the work to come, of both the hyperbole and the author’s tendency to explain everything to the reader. But then, the book is promoted not as a serious biography but as a ‘romance gone wrong’. Written by a Fairfax investigative reporter, it reads like an extended feature article, with the historical strands teased out but little empathy with its main characters.

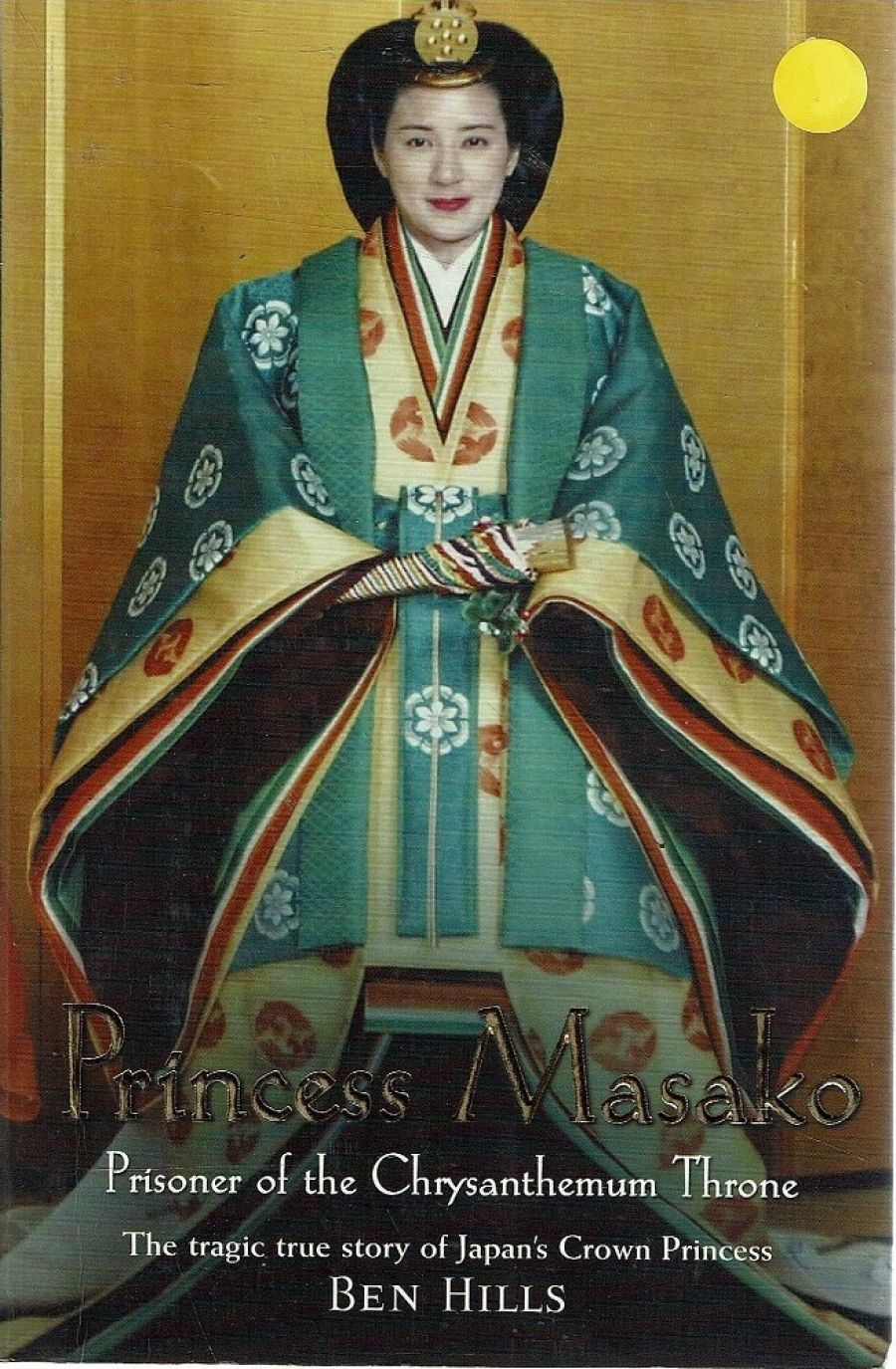

- Book 1 Title: Princess Masoko

- Book 1 Subtitle: Prisoner of the Chysanthemum Throne

- Book 1 Biblio: Random House, $34.95 pb, 320 pp

One facet of the ‘tragedy’ is the lack of an heir to the Japanese imperial line. Crown Prince Naruhito and his wife Masako had one daughter in 2001, after clandestine IVF treatment, but no son and heir had arrived by the time Masako reached her early forties. The debate that surfaced in Japan about the solutions to the problem, including the possibility of allowing women to inherit the imperial throne, is traced through Japanese and overseas media reports, and through Hills’s numerous interviews.

The book went to press at the time of the birth of Prince Hisahito to Masako’s sister-in-law in September. It is clear in the final chapter that there has been a hasty revision to incorporate the news that a male heir has finally been born to the Japanese monarchy. Unfortunately, there was no revision to a comment in the penultimate chapter that ‘in 40 or 50 years’ time … the imperial line will also come to an end.’ This is just one of several glitches in a work that suffers from hasty writing and editing.

It is inevitable that Hills would be unable to give us the inside story ‘behind the Chrysanthemum curtain’. He only glimpsed Masako once, at a train station. He had no chance of interviewing her, or any of the imperial family who lived within the walls of the palace. Of those relatives and friends to whom he had access, many were unwilling to speak up against the Kunaicho, the Imperial Household Agency which arrives, as the story begins, at Masako’s family home in order to take her into their custody on her wedding day.

It is a fascinating premise for a story, all the better for being true. A Harvard-educated woman – raised in Japan, Russia and America, and evolving into a gifted diplomat – is courted by the future Japanese emperor, and finally accepts his proposal. Hills does not claim to understand why Masako made that decision, despite knowing how debilitating the experience had been for other royal wives. He surmises that she felt she might be able to play a role in modernising the monarchy. Nor does he draw any conclusion about her character or motivation; he simply quotes the conflicting views of her friends and associates that show her personality was at times Westernised and assertive, at others demure and traditionally Japanese.

Hills has an informal approach to his text, a light touch that crosses at times into the flippant, rather at odds with the subject. The lovers are ‘star-crossed’, a royal retainer ‘a pompous old fossil’, Masako’s ladies-in-waiting ‘bitchy biddies’.

The most engaging part of Princess Masako is the story of Masako’s earlier life and education, mainly because there is more information on this part of her life than on her time in Japan. There is a less interesting chapter devoted to Naruhito’s education, which includes his time at Oxford and as a home student in Australia. The development of Masako’s career is an important prelude to the fundamental change in her life since she has been in thrall to the Imperial Household Agency. Unfortunately, although Hills builds the suspense, the outcome is uncertain. We do know that Masako is suffering from depression; we do not know if she is still hoping to produce a son. Hills admits in his preface that this is not the final word on the subject, but does allow himself gloomy predictions for her future on the final page.

Hills states his purpose clearly. As well as writing about ‘a romance gone wrong’, he is exploring contentious social issues in Japan: the role of women, IVF treatment, attitudes to mental health and the monarchy. It seems the Imperial Household Agency is instrumental in barring changes in Japanese society. The prevailing attitudes and debates are well covered, although there is no adequate exploration of how the Imperial Household Agency manages to maintain its power without challenge.

Hills, who is married to a Japanese photojournalist, has spent three years as a correspondent in Japan and is the author of Japan: Behind the Lines (1996). This latest contribution to our understanding of Japan is lightweight but provocative.

Comments powered by CComment