- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Politics

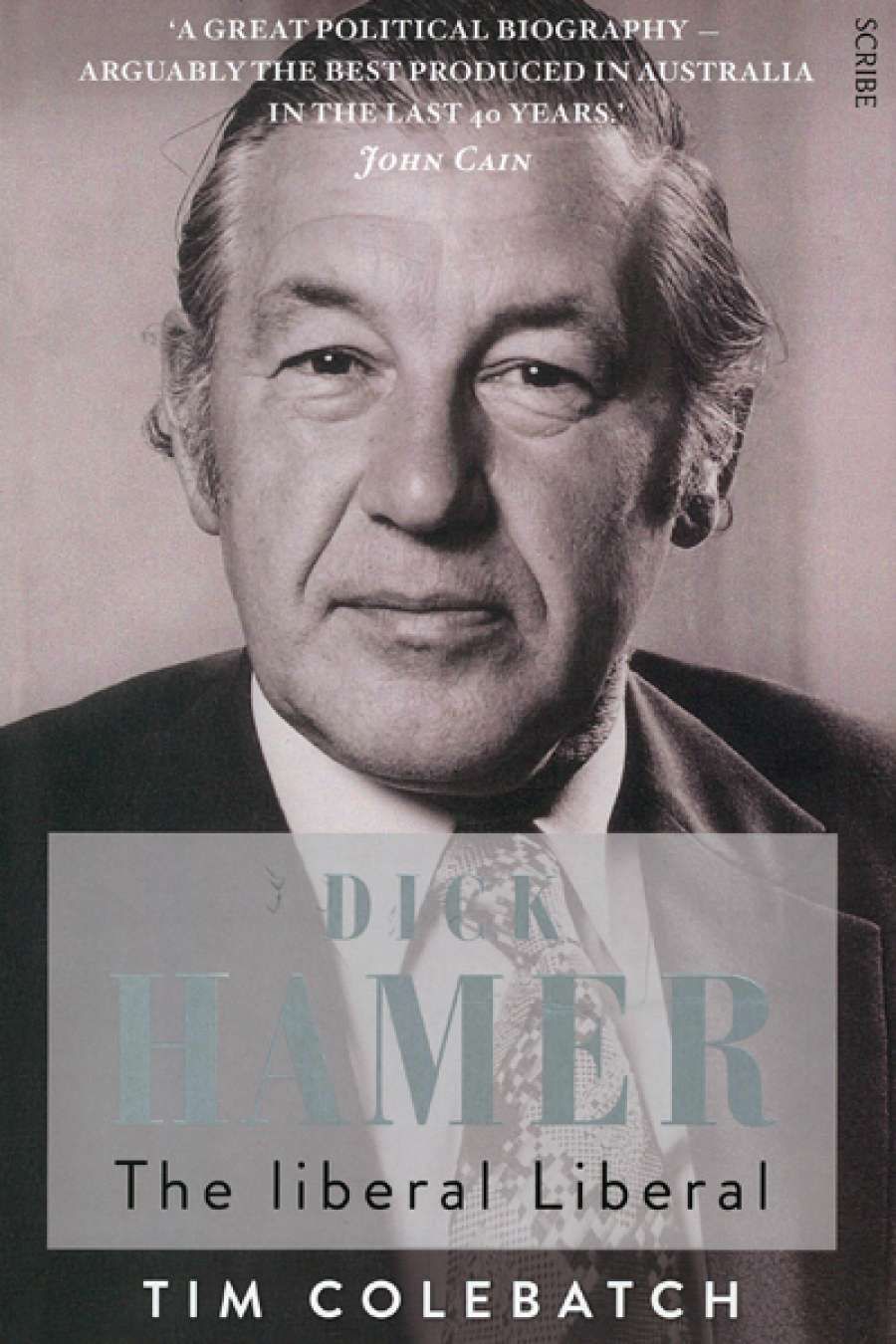

- Custom Article Title: Geoffrey Blainey reviews 'Dick Hamer' by Tim Colebatch

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Portrait of an unlikely heir to Henry Bolte

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Rupert (‘Dick’) Hamer proved to be one of Australia’s most innovative premiers. One sign of his unusual prestige is that this history of his life and times has perhaps been publicly praised more by Labor leaders than by his own Liberal colleagues.

Hamer’s family background was in the church, law, business, and politics. His paternal grandfather was the minister of the wealthy Independent Church (now called St Michael’s) on Collins Street, where he was distinguished for his highbrow sermons and the astonishingly high salary he received. Hamer was born in 1916 and was formally christened Rupert after a relative who had died at Gallipoli the previous year. He was a studious boarder at Geelong Grammar, eventually winning first class honours in three languages – Latin, French, and Ancient Greek. A school friend described him as never ‘fussed or flustered’. Those qualities remained with him. He could come home to suburban Canterbury after a turbulent week in parliament and sleep like a rock, then dig happily in the garden next morning.

- Book 1 Title: Dick Hamer

- Book 1 Subtitle: The liberal Liberal

- Book 1 Biblio: Scribe, $59.99 hb, 511 pp

Hamer’s legal career had barely begun when he enlisted: he served as an officer at Tobruk and El Alamein and in New Guinea, where he caught malaria. In 1944, before going to another military posting in Britain, he married April Mackintosh. He did not enter politics until he was in his early forties, but in those then-puritanical eastern suburbs of Melbourne he was soon singled out as a leader.

In the 1960s, Hamer fitted neatly into Henry Bolte’s team. Ministers were not expected to create a stir: this suited Hamer, who made his name through sheer competence rather than television appearances. For nine years Hamer was minister for immigration or for local government before becoming deputy premier and the heir to Bolte, who in 1972 returned to his farm and the racecourse.

Tim Colebatch vividly paints the stage and scenery of Victorian politics. He is illuminating on what he prefers to call the ‘Bolte–Rylah government’, the most enduring in Victoria’s history.

Bolte is remembered for his tough, one-sentence asides, usually spoken with a smoking cigarette in his fingers; but most of his major deeds are forgotten. He made Victoria the first territory in the world to compel motorists to wear seatbelts, though we learn that he was not personally an enthusiast for his own reform. With the aid of a strong economy, Bolte built more secondary schools than all the previous governments of Victoria put together. Along St Kilda Road, his government created the grand and outwardly sombre National Gallery of Victoria. This was a brave cultural adventure for a farmer who read not one of the books in the library of his own parliament house. The banning of books was a hallmark of his government.

It is odd that Bolte and Hamer, with personalities as different as a chainsaw and a fountain pen, should lead, in turn, the same party. It was for long a strength of Victorian Liberals, even in the era of Alfred Deakin, that a radical and conservative wing could inhabit the same nest. Bolte and Hamer stood on opposite sides in the summer of 1966–67 when the Ronald Ryan case had to be resolved. Ryan had been sentenced to death for the killing of a prison warder at Pentridge. Bolte and most members of his Cabinet thought that the crime was so callous and so destructive of public order that Ryan should be hanged. The three Melbourne dailies opposed the hanging. According to this book, ‘Hamer felt so strongly against the hanging that he broke the family holidays and drove the 300 kilometres from Metung to take part in the final cabinet vote.’ What actually happened at that tense Cabinet meeting has since been widely debated, partly because, half a dozen years later, Hamer, as premier, successfully introduced a bill to abolish the death penalty in Victoria.

Bolte and Hamer toast each other at the opening of Kryal Castle in Ballarat November, 1974 (photograph taken from title)

Bolte and Hamer toast each other at the opening of Kryal Castle in Ballarat November, 1974 (photograph taken from title)

Almost certainly, on the day when Bolte presided at Cabinet, Hamer did speak against the hanging of Ryan. But it is likely that, for the sake of ministerial unanimity, he was finally persuaded to vote with Bolte. The memoir of one minister, Vernon Wilcox – a book rarely consulted – reports that the vote was unanimous. I am not sure whether Colebatch would agree with this interpretation.

The anti-hanging argument is now seen as overwhelming in its compassion and logic. It has been almost too successful. Ryan is now a hero–victim, but the warder who lost his life is forgotten. His name does not appear in this book; nor do I remember it.

Even after half a dozen years in parliament, Hamer was viewed as a coming leader. When R.G. Menzies thought of retiring as the eternal prime minister, he privately expressed the wish that his federal seat of Kooyong should be filled by Hamer. To Menzies’ surprise, the much younger man declined; Hamer preferred to live and govern in Melbourne.

Just before Gough Whitlam was about to transform federal policies, Premier Hamer was starting to steer Victoria with his version of the same new-age compass. In guarding the environment Victoria reportedly led the nation; ‘it was also a great age for the arts’, writes Colebatch. Hamer himself became Victoria’s first minister for the arts as well as premier and treasurer. Victoria spent heavily on teachers, whose numbers grew at a much faster pace than students. Hamer’s government financedthe Underground, with its twelve kilometres of tunnels, and it also chess-boarded Victoria with new national parks.

During most of his nine years as premier, Hamer was often the kind of person who was more likely to be leading a moderate Labor government. That made him vulnerable. In the end his own party, the darkening economic climate, and the prospect of a revitalised Labor opposition combined to topple him.

Dick Hamer and Joh Bjelke-Peterson January, 1974 (photograph taken from title)

Dick Hamer and Joh Bjelke-Peterson January, 1974 (photograph taken from title)

Hamer had personal charm and a quiet forthrightness that does not always go with charm. Colebatch writes that he seemed to be ‘impervious to criticism’. But when he was forced out in 1981, the event ‘broke through all his psychological defences’. The next few years (‘the worst of his life’) were marked by ‘uncharacteristic errors of judgment’.

Later, he absorbed himself on the boards of business and cultural organisations, especially the Victoria State Opera. After becoming a republican, he stood unsuccessfully for a seat at the constitutional convention held in Canberra in 1998. He protested against the placing of foreign women and children in detention camps in Australia and Nauru. He became a leader in search of a party.

Dick Hamer is one of the most compelling books on Australian politics I have read. The narrative is strong and the prose is fluent. The book makes me realise how, in writing the modern history of the nation, we too often focus on federal politics, forgetting that most of the political decisions that shaped human lives were made far from Canberra.

Comments powered by CComment