- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Politics

- Custom Article Title: Neal Blewett reviews 'My Story' by Julia Gillard

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The coup that doomed two Labor prime ministers

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Much like her government, Julia Gillard’s memoir resembles the proverbial curate’s egg. Where her passions are involved, as with education (‘Our Children’) or the fair work laws, we are provided with a compelling policy read. Where they are not, as in large slabs of foreign policy, the insightful competes with the pedestrian, enlivened admittedly with her personal talents in handling the great and the good – handballing a football with Barack Obama in the Oval Office, for instance. A chapter on ‘Our Queen’ and the republic is rather jejune, though Gillard has a nice line on changes in the royal succession as providing ‘equal rights for sheilas’. The fact that ‘every prediction the departments of Treasury and Finance ever made about government revenue turned out to be wrong’ makes for dispiriting reading on fiscal matters.

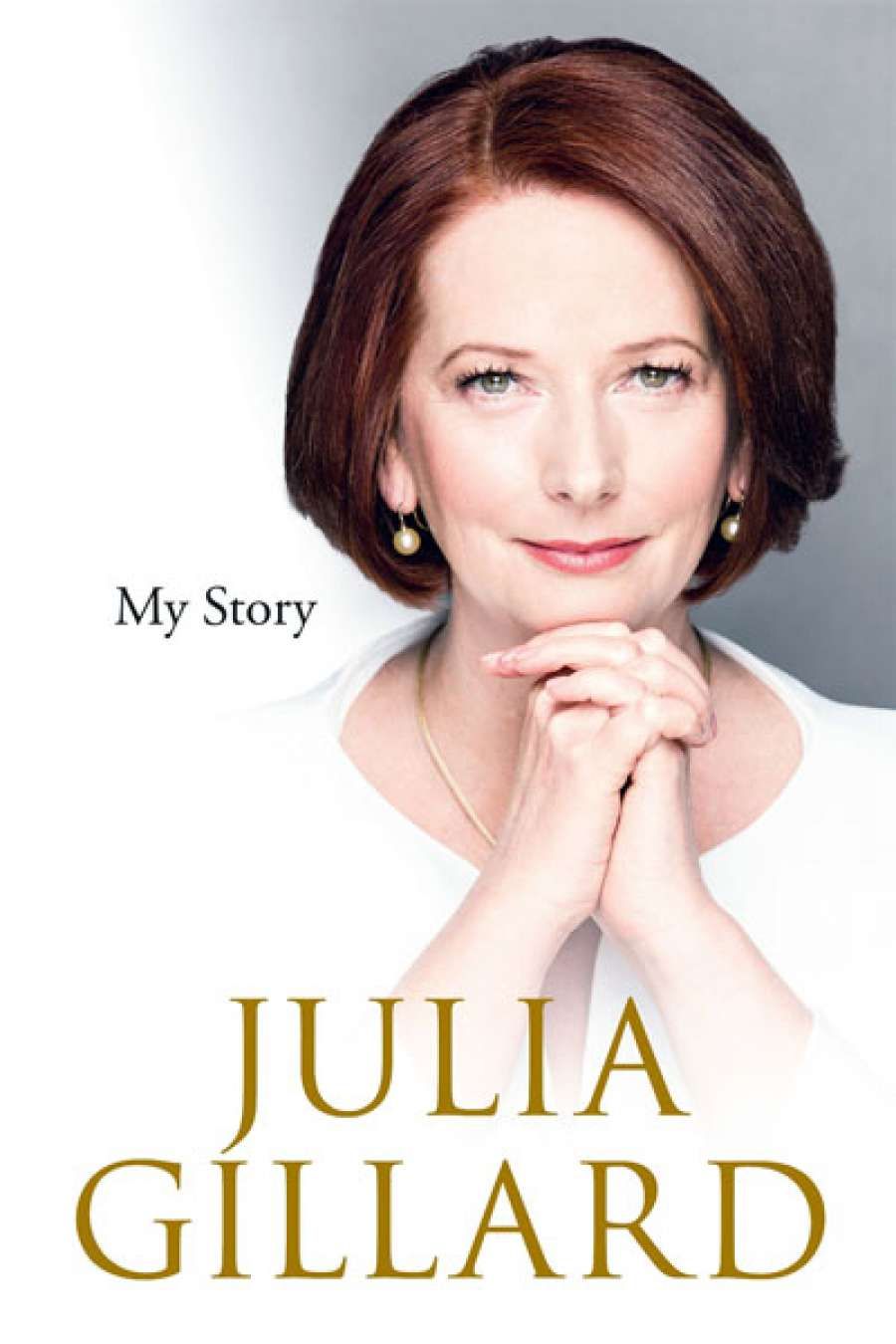

- Book 1 Title: My Story

- Book 1 Biblio: Knopf, $49.99 hb, 512 pp

On first meeting Gillard, the no-nonsense Angela Merkel queried, ‘What happened to Kevin?’ We are not given Gillard’s response to the German chancellor, but the answer is a major theme of My Story. However the explanation is not well served by the structure of the book. Part One – a little under one third of the work – provides a political narrative; the remainder deals mainly with the policy issues she confronted. The result is to separate politics from policy. Again, this divorce could be said to be characteristic of her government. The early political story might be entitled ‘Gillard versus Rudd’, for its subject is the personal tension at the heart of the party and government. But the separation between politics and policy means that, for a full understanding of events mentioned in the political narrative, we can wait many hundreds of pages and are sometimes left as a result with differing impressions.

Julia Gillard (photograph by Sophie Deane, Museum of Australian Democracy Collection)

Julia Gillard (photograph by Sophie Deane, Museum of Australian Democracy Collection)

In the first part of the book, Gillard notes that by 2010 ‘Kevin was completely spooked by the way the politics of carbon pricing had withered’ and that he drifted on the issue for months, but we have to wait for some 300 pages before we find a detailed account of the critical role played by carbon pricing in Rudd’s demise. Similarly, while there are a couple of out-of-context references to boat people in the early political narrative, we have to wait some 400 pages for any sustained attention to the issue. And then, of all things, it is dealt with as an internal party problem, just one aspect of the tension between ‘progressive activists’ and the ‘traditional blue-collar constituency’. Such is the distorting prism through which too many in the Labor party see one of the great moral issues of our time. Likewise, while we learn early on that the miners’ response to the proposed mining tax had a ‘devastating political impact’, the shambolic evolution of that tax awaits us another 300 pages on.

These débâcles share common features. First, with the Cabinet virtually discarded, there is a highly centralised government around a prime minister obsessed with tactics rather than strategy, a man prone to micro-management who found it impossible to delegate and whose haphazard decision-making style Gillard likens to a ‘scatter-gun approach’. Decisions on boat people and the mining tax seem to have been in the hands of the Strategic Priorities and Budget Committee (SPBC) – the so-called ‘gang of four’ – Rudd, Gillard, Wayne Swan, and Lindsay Tanner – which had emerged as the key governmental body during the GFC. This had the effect of excluding Chris Evans, the immigration minister, from decisions in his own portfolio. He was apparently not consulted before Rudd’s intervention in the Oceanic Viking, which Gillard describes as a media tactic that ‘generated positive attention for a few days and then was a disaster for a month’. Similarly, the SPBC left Martin Ferguson, the mining minister, out of the inner circle on the mining tax, which may well explain the mixed messages the mining industry received prior to the announcement of the tax. A troika had responsibility for carbon pricing. It included the minister responsible, Penny Wong, plus Rudd and Swan, but left out many in the Cabinet with expertise in the area.

Julia Gillard 2010 (photograph by Troy Constable)

Julia Gillard 2010 (photograph by Troy Constable)

Gillard concludes that ‘Kevin was a procrastinator in the face of big strategic decisions’. Torn between the strategic advantage of making a deal with Malcolm Turnbull in order to pass the Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme and the tactical advantages of wedging Turnbull on the issue, Rudd equivocated. As a result, he lost both Turnbull as Opposition leader and the CPRS. This disaster was compounded by the failure of Copenhagen, so that by early 2010 Rudd on this issue, according to one of his staff, was ‘in funksville with no map about how to get out’. For four months, key ministers argued whether they should stick with the scheme and possibly go to an early election on it, while Rudd secretly sought polling advice as to how he could explain delaying action on ‘the great moral issue of our time’. The budget compelled a public decision in mid-April, and Rudd’s explanation of the postponement was, in Gillard’s words, ‘clear as mud’. With this his personal ratings plummeted. In these months of drift Gillard herself had favoured a decision for delay, but above all was ‘fed up to the back teeth with [Rudd’s] procrastination on carbon pricing ... [and] I consistently told him that if the call was to fight for the CPRS as the key election issue, then I was ready to fight’. On the mounting flow of boat people in 2010, ‘Kevin did not meaningfully and continually engage with the problem.’ On the mining tax, her verdict is succinct and damning: ‘Kevin procrastinated his way into [the mining tax].’

The result was that by mid-2010 a host of unresolved major problems faced the government: carbon pricing was postponed, apparently indefinitely; the government seemed helpless in face of asylum seekers; the effort to finesse something useful, the mining tax, from the Henry tax review, had led to a politically damaging clash with the mining industry. In addition, Rudd had embarked on complex health reforms, apparently as a diversion from his other worries. In 2010, according to Gillard, ‘Kevin’s demeanour was now unremittingly one of paralysis and misery.’ A newspaper story on 23 June 2010suggested that Rudd no longer trusted his deputy. This triggered her acquiescence in a party revolt which led to the overthrow of Rudd the following day. Her ‘strong belief that after some recovery time, [Kevin’s] dominant emotion would be relief – he had become so wretched while leader’ – suggests that, after four years as his deputy, she had little understanding of the man she had dethroned.

Barack Obama and Julia Gillard handballing a Sherrin in the Oval office, 2011 (photograph by David Foote – AUSPICS/DPS)

Barack Obama and Julia Gillard handballing a Sherrin in the Oval office, 2011 (photograph by David Foote – AUSPICS/DPS)

Julia Gillard’s prime ministership never escaped the consequences of her decision to head the insurrection against Rudd. Most obviously, it triggered a feud with Rudd which did not cease until she herself was unseated in June 2013. Rudd may have been, as she writes, ‘a highly disorganised prime minister’, but he was ‘a ruthlessly organised political plotter’. Gillard makes a powerful case that Rudd and his allies were the source of the leaks that helped sabotage her election campaign in 2010. She argues that during the campaign he blackmailed her into promising him the foreign affairs portfolio. ‘I had little choice,’ she writes. ‘I had to stop what I considered to be the acts of treachery on his part.’ By mid-2011 Rudd was beginning to stalk her. Using her dismal polling as justification for his return, he engaged in ‘a danse macabre’ with acquiescent journalists, while he and his lieutenants became ‘a supportive Greek chorus to Tony Abbott’s hard-hitting negative campaign against [her]’. She crushed him in the ballot in February 2011, but the bloodletting around that contest deepened the fissures within the party. A year later came the farcical non-challenge, precipitated by Simon Crean, who gets the sharp edge of Gillard’s tongue. Four months later she went down to defeat, but not without a fight. Penny Wong pleaded with her in tears that it would be ‘easier’ if she did not contest. ‘You mean easier for you, Penny’, was the chilling reply.

Moreover, the sudden and unexpected overthrow of Rudd cast a pall of illegitimacy over her prime ministership, which Gillard was never able to shake off. She ‘came to regret’ that in an effort ‘to treat Kevin respectfully’ she had offered no public explanation of his overthrow. ‘A good government that had simply lost its way’ was just not good enough. How could a ‘good government’ claim credit for its record after having just executed its leader? Neither she nor any of the rebels seems to have recognised that the surprise sacking of an elected and still-popular prime minister would make it very difficult to capitalise on his government’s achievements in an election only months away.

Then there were the ‘political headaches’ she inherited from Rudd. The most diabolical of these was carbon pricing. After a wayward beginning during the 2010 campaign – her proposal for a Citizens’ Assembly was widely ridiculed, and even she admits that Cash for Clunkers ‘was a dog’ – she got into her stride with the hung parliament. Marshalling a motley group of Greens, Independents, and experts, ably managed by the astute Greg Combet, she produced an elaborate and comprehensive proposal, basically an emissions trading scheme with a three-year fixed price, accompanied by major commitments to renewable energy. Unlike Rudd, she secured its passage through the parliament and saw it in operation by 1 July 2012. But if the policy was impressive, the politics were abysmal. She compounded her unwise pledge during the 2010 campaign (‘there will be no carbon tax under a government I lead’) by foolishly conceding that what she had produced could be called a tax. She confesses: ‘It is the worst political mistake I have ever made, and I paid for it dearly.’ She remains adamant that she ‘did not lie. I had never intended a carbon tax and did not introduce one.’ Technically she is correct, but the hoi polloi were not listening. During the gestation of the scheme, the politics had become toxic.

On the second of her ‘headaches’, the mining tax, Gillard got the politics right, but at the expense of poor policy. After becoming prime minister, she secured the urgent settlement she needed with the miners in eight days, but after allowing for all her caveats, the revenue returns from the tax suggest the big miners took her and the treasurer for a ride. On the most intractable of the headaches – the boat people – she made no progress, despite a reputation for toughness on the issue. The ill-prepared election gambit of processing refugees in Timor-Leste fell flat, while her Malaysian solution was frustrated by an activist High Court and the unremitting negativity of the Opposition. Given that the Abbott government now contemplates dumping boat people in Cambodia, their resistance to her Malaysian solution warrants her castigation of them for their ‘sick-making double standards’. She credits Rudd, at his second coming, for the Papua New Guinea solution which saw asylum-seeker boat numbers plummet.

It is a relief to turn to those policy areas free from the baneful shadow of Kevin Rudd. Insofar as Gillard was driven by any single purpose, it was the pursuit for all of ‘a fair go through a great quality education’. She wanted education ‘to be at the centre of my government because of its life-changing power’. The development of a national curriculum was pushed ahead despite much arguing from the states. The establishment of the My School website involved making public and transparent ‘a rich treasure trove’ of existing information in order to lever further change. To achieve this she had to face down the federal opposition, some of the state governments, and the education unions. Most important of all were the Gonski proposals to reform school funding on a genuinely needs-based platform. In Gonski and the National Disability Insurance Scheme – ‘the biggest way of responding to need since Medicare’ – both of which involved complex negotiations with the states, we see again her negotiating skills in action. Setting deadlines and corralling the Labor jurisdictions to secure momentum, then providing incentives and pressures to bear on the reluctant states – ‘You’ll lose political skin’ – she secured her objectives.

Kevin Rudd (right) and Julia Gillard (left) at their first press conference as leader and deputy leader of the Australian Labor Party on 4 December 2006.

Kevin Rudd (right) and Julia Gillard (left) at their first press conference as leader and deputy leader of the Australian Labor Party on 4 December 2006.

Gillard brought to completion a number of Howard initiatives: the establishment of the largest network of marine parks in the world and the implementation of the Murray-Darling Basin plan. She was midwife to the Tasmanian Forests agreement, an issue which she likened to ‘political kryptonite’. She refused to impose an outcome, believing that the parties themselves must reach agreement, but she provided an invaluable facilitator in Bill Kelty, offered financial rewards for a satisfactory agreement, and intervened to secure an independent verification process.

My Story is both a heroic and a tragic tale. Heroic in that no prime minister in modern times has ever been under such sustained and unremitting attack from without and within. The chapter titled ‘The Curious Question of Gender’ reminds us again of one of the more shameful episodes in Australian political history – the licence gender gave to the appalling treatment of our first female prime minister by many of her political foes and media critics. Heroically, she ‘toughed it out’ (her words) with an equanimity rarely lost, except perhaps in the famous misogyny speech. Even her enemies would concede that she had resilience in spades. It was tragic in that a flawed decision was her undoing. Gillard did not have to accept the leadership of the insurrection against Rudd at that time. Without her it could not have succeeded. A showdown with Rudd was probably inevitable, but surely not just a few months before an election. As it was, her decision ultimately doomed two prime ministers and a Labor government.

Comments powered by CComment