- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Film

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

‘I get awful intense about these movies I do. I become, in fact, obsessed with them.’ So Elia Kazan (1909–2003) wrote to his daughter in 1957. A workaholic, Kazan was both extremely self-assured and plagued by self-doubt, terrified he would produce mediocrity. He rarely did. As a stage and screen director he achieved remarkable success. Kazan was an egotist, and the confidence he exhibited publicly, and in these letters, is at once impressive and repugnant.

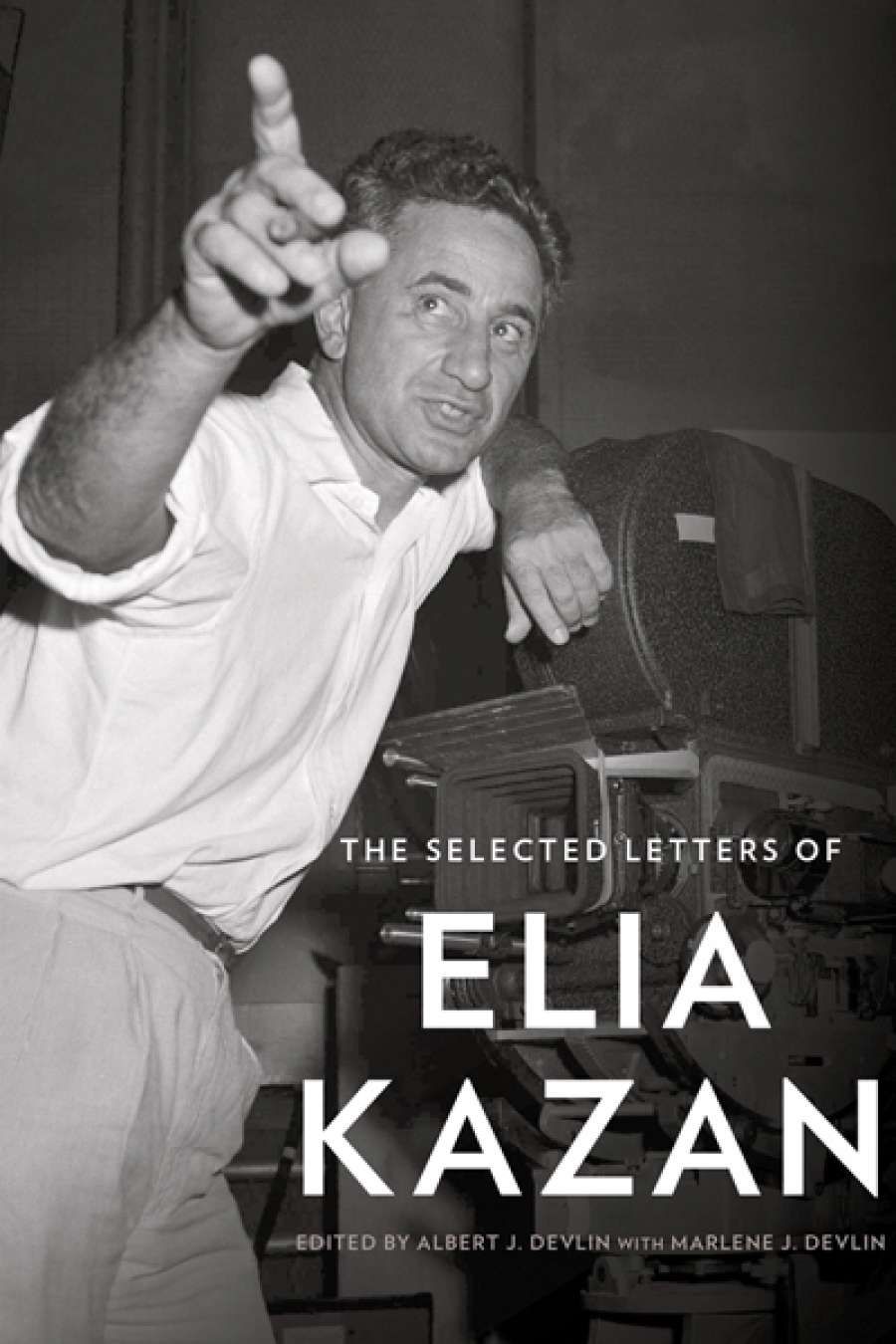

- Book 1 Title: The Selected Letters of Elia Kazan

- Book 1 Biblio: Knopf, US$40 hb, 649 pp

In his memoir titled A Life (1988), Kazan recalled that his third wife, Frances, would ask him why he was mad with her. He wasn’t, he insisted: ‘It’s just my face.’ In this book of nearly three hundred letters, selected from about twelve hundred, Albert J. and Marlene J. Devlin search behind this daunting face to compose a portrait of a man whose generosity is masked by a tough exterior.

Kazan’s impact as a director was undermined for many by his cooperation with the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1951. At first refusing to name names, he eventually admitted to being a member of the Communist Party and volunteered information about several others. His justification was that he knew both the follies and dangers of the group and their principles, and that they were destroying his public face and his career. Making On the Waterfront (1954) in subsequent years, Kazan believed the story of a man who betrays one loyalty for another to be an honourable one; Marlon Brando was maddened when he realised that his role was partly intended to excuse Kazan’s behaviour.

While his reputation recovered at the time, it remains tainted; as an ‘informer’ he did not have it easy. When the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences awarded him a Lifetime Achievement Award at age eighty-nine, their decision was met with protests. Yet it is impossible to deny the impact that Kazan had on the industry, despite being initially repelled by Hollywood and vowing never to work there. He facilitated the film débuts of an extraordinary range of talent, including James Dean, Warren Beatty, Eva Marie Saint, Eli Wallach, and Andy Griffith. He fought against a censorship that he classed unfair and injurious to the arts and the industry.

As is to be expected from a life as vast as this, there are plenty of glimpses into the machinations of the Hollywood system. In 1953, Kazan, who was at that stage unsatisfied with Brando for On the Waterfront, wrote to Budd Schulberg of two unknowns who were lined up for consideration. One of these, he revealed in a following letter, was Paul Newman, who was yet to star in a picture but about whose eventual stardom Kazan had ‘absolutely no doubt’.

Following the completion of A Streetcar Named Desire (1951), Kazan wrote to Jack Warner at Warner Bros. to praise the work of the film’s editor, David Weisbart, and suggest his talents be used further in the motion picture business; Weisbart would eventually produce Rebel Without a Cause (1955). In a letter to playwright Eric Bentley, Kazan emphatically opposes a suggestion that he co-authored either Streetcar or Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman, but speaks openly and firmly about the role of a director only in shaping an author’s work, not writing.

While not always satisfying, these letters bring a new perspective to Kazan’s character. Guided by two principles of importance and range, the Devlins have fulfilled their framework, and while it is already a long book, the latter suffered from some chronological ellipses. The annotations are thorough and illuminating, but the absence of ‘the other side’ – letters from Kazan’s correspondents – is at times keenly felt. This is perhaps most evident in correspondence with his first wife, Molly, from whom he famously took leave multiple times to pursue affairs with other women. His proclamations of love and hostility burn with equal passion; what of hers?

Kazan had long-lasting friendships, and business relationships, with many writers and artists, with some correspondences lasting decades. Some letters published here were never posted. This suggests a rarely seen caution in Kazan’s disposition; these particular letters are some of the most exciting. Not one to hold back in any emotional realm, he curses his friends and offers them his everlasting love.

While Kazan described cinema as ‘the most important of all of the performing arts’, he was dedicated to his work in the theatre, and later on as a novelist. Starting in his youth, these letters reveal a disposition becoming more entitled and more passionate, although no less warm, as he ages. He directed his final film, The Last Tycoon (1976), somewhat unwillingly, yet he must have seen something of himself in its fictionalised Irving G. Thalberg character. ‘He wanted to give the work he was engaged in respect and thereby give his life dignity,’ wrote Kazan. Reading these letters, it is impossible not to think the same of him. As a film-maker, Kazan favoured the close-up: shots that penetrate the eyes of his characters and reveal their deepest emotions. This book provides the same experience, only through epistolary rather than cinematic means, providing a vast and almost uncensored insight into Kazan’s life.

Comments powered by CComment