- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Media

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The human cost of Fairfax’s decline

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

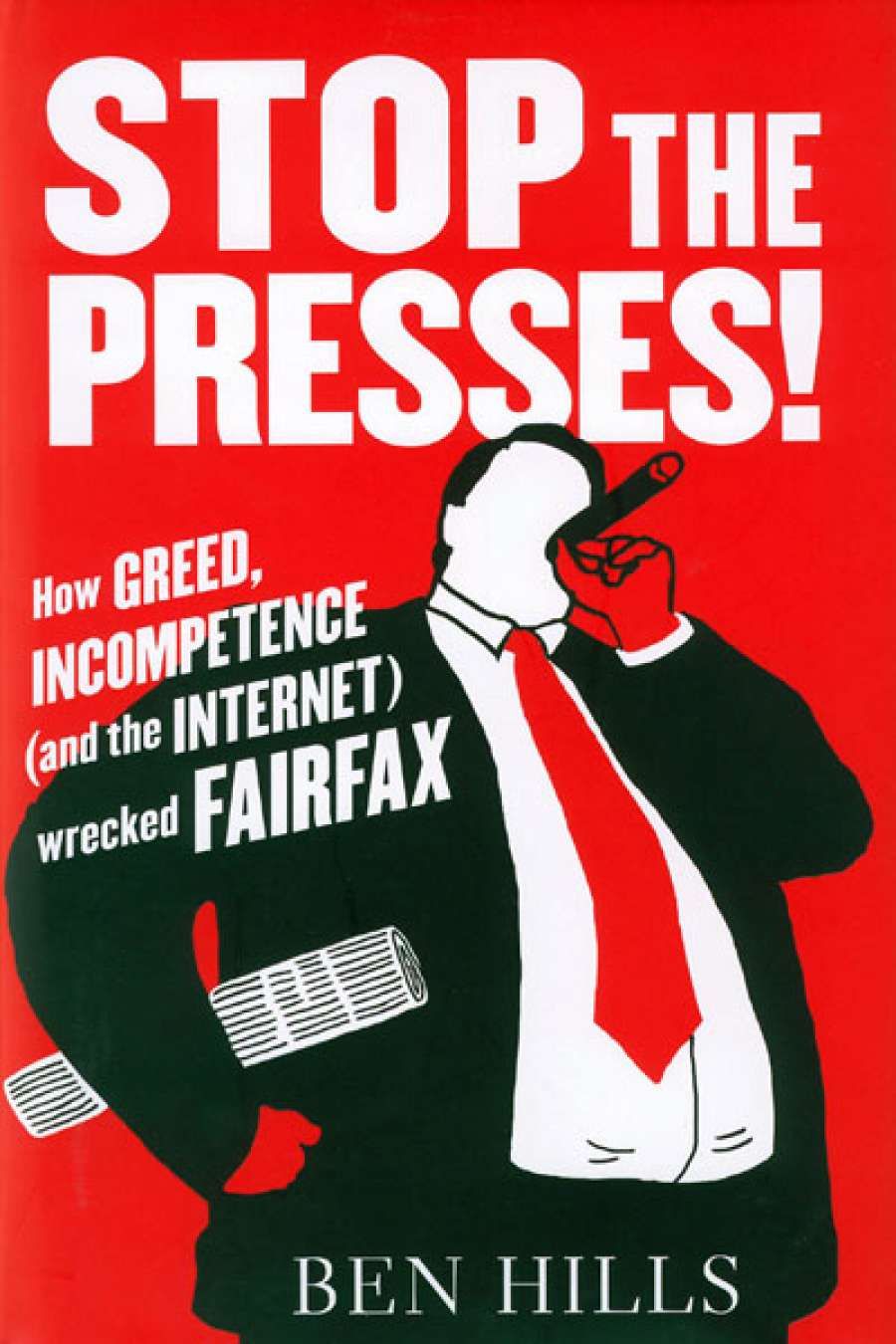

Fairfax Media, which has churned out millions of words since its beginnings in Sydney in the 1830s, has itself inspired hundreds of thousands of words in the last year or so. First came Colleen Ryan’s Fairfax: The Rise and Fall (June 2013), followed by Pamela Williams’ Killing Fairfax (July 2013). Now comes Stop the Presses! by Ben Hills, a veteran investigative journalist who would no doubt self-identify as a ‘Fairfax lifer’, like many characters in his book. Just in case the theme of these tomes isn’t clear, we have Hills’s subtitle: How Greed, Incompetence (and the Internet) Wrecked Fairfax.

- Book 1 Title: Stop the Presses!

- Book 1 Subtitle: How greed, incompetence (and the internet) wrecked Fairfax

- Book 1 Biblio: ABC Books, $39.99 hb, 394 pp

Hills adopts a slightly more historical approach than his competitors. His first chapter (tellingly and elegiacally entitled ‘Rivers of Gold’, an allusion to Fairfax’s fabled near monopoly on classified advertising) is a kind of short history of the company, focusing on Fairfax’s successful adaptations to the challenges of new media in the form of radio and then television. It finishes on the eve of the disastrous attempt at privatisation by ‘young Warwick’ in 1987, covered in the next chapter. Hills appears to have relied largely on Heralds and Angels (1992), which he describes as ‘Gavin Souter’s exhaustive history of the company’– this is actually a book principally about post-1987, with Souter’s Company of Heralds (1981) constituting the exhaustive history. This earlier volume does not appear in Hills’s source notes at the end of his book. (Nor, for that matter, do the years of publication for the books he cites. For all the reader knows, J.D. Pringle could have been writing at the same time as Fred Hilmer and Bruce Guthrie.)

Stop the Presses! begins with the dramatic June 2012 announcement from CEO Greg Hywood of the loss of 1900 jobs – ‘the greatest diaspora of journalistic talent this country has ever seen’. But Hills focuses not just on the impact on the metropolitan workforce, but on printers and on country newspapers. He takes us from printing plants in Chullora and Tullamarine, to Cobar in the far west of New South Wales, where in October 2012 Fairfax Regional Media announced the closure of the 125-year-old Cobar Age. One of the great strengths of this book is its attention to the development of Fairfax’s rural interests. Perhaps inspired by his journalistic apprenticeship at Stanthorpe in the 1960s, Hills explores the unique role of country newspapers in local communication and communities. He does not just trace their decline at the hands of the rise of broadcasting and the Internet, but explores the emergence of a business model ‘for the new breed of bottom-line-driven country press proprietors’: buying up family-owned newspapers, cutting staff, sharing editorial and advertising copy, and centralising production and printing at regional centres.

The book is based largely on eighty interviews, although Hills was not able to interview Lady Fairfax or Gina Rinehart. His brief audience with Roger Corbett was off-the-record; in contrast, Fred Hilmer, CEO from 1998 to 2005 and the man who bears the ‘heaviest responsibility’ for the decline of Fairfax, submitted himself for interview. Hills explores, compellingly, the human cost of cut after cut. He has worn out boot leather travelling beyond Sydney and Melbourne, and has drawn extensively on (at times apparently delusional) annual reports. But there is a curious statement about the Fairfax Archives being ‘hidden away in a warehouse somewhere in Alexandria; access to them is denied even to historians seeking to study Sydney’s bygone days’. I for one know the address, and while access can be difficult, it is not impossible.

There are also disappointing factual errors from the pen of such an experienced journalist. The Sydney Morning Herald is described as the only Sydney newspaper started in the nineteenth century to survive; the Daily Telegraph, launched in 1879, continues. Gerard Noonan is not a former editor of the Herald, but of the Australian Financial Review. Alan Jones is a breakfast, not a ‘morning’, radio presenter. TCN9 – and thus television in Australia – started in September 1956, not, as implied, in November. Fairfax’s ‘Good Food Week’ has long been a month-long affair. The Pacific Area Newspaper Publishers’ Association is referred to as the ‘Press’ Association, and the Journalism Education Association of Australia as the ‘Educators’ Association. The Conversation is funded by several universities, but not by the Group of Eight.

Other points might be open to dispute. Describing the nineteenth-century John Fairfax as a ‘Liberal’ in the context of a discussion of the Herald ’s conservatism has a particular, post-1944 connotation. Mike Carlton, labelled as one of 2UE’s ‘few stars’ in recent years, might not have left solely due to fatigue in 2009, but due to poor ratings.

The book is fast-paced, if occasionally over-written. Light and acerbic touches – from ‘Chief executive numbers seven and eight came and went, barely touching the scorer’ to ‘boardroom bedlam’– are counter-balanced by clichés too plentiful to list. Pen portraits are vivid: Gary Linnell is ‘[t]all, lean to the point of gauntness, with a shaven head and a mouth like a knife slash’; Mike van Niekerk ‘has the taut face, like a surgical glove full of pebbles, of a competitive cyclist’. But the feature writer’s style begins to become tiring, if not gratuitous. Do we really need to know that the journalism academic Jenna Price ‘struggles with her weight – her nickname used to be “the killer tomato”’?

Breakout quotes, generally about what was happening elsewhere in the global media industry or mapping the rise of the Internet, are dispersed throughout the book, although they are sometimes simply distracting. Much of the final chapter is a generalised discussion about the challenges facing newspapers, and could appear in almost any ‘future of journalism’ forum. Indeed, while the Ryan, Williams, and Hills books will be mined by future generations of Australian media and business historians, it is difficult to grasp their audience. Is it the 8042 journalists who belonged to the Media, Entertainment and Arts Alliance in 2007?

Written with ‘as much sadness as anger’, Stop the Presses! is about a media company without a proprietor or a dominant shareholder. I am not entirely convinced it answers the question posed on the first page: ‘what will it mean for the public’ if the Herald and the Age disappear? Hills is sentimentally attached to the ‘golden age’ and ‘glory days’ of Fairfax – just as he was to the ‘golden age’ of Graham Perkin, the subtitle of his last book (2010). The author doesn’t really engage with the ruminations of one of his most incisive interviewees, Eric Beecher, about who might ‘embrace and pay for a new kind of journalism that did not owe obeisance to the macho, gotcha, hold-the-front page mentality that still, amazingly, lies at the heart of the Fairfax editorial mindset’. For my money, the best book on the ‘heritage media’ group remains Souter’s Company of Heralds.

Comments powered by CComment