- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

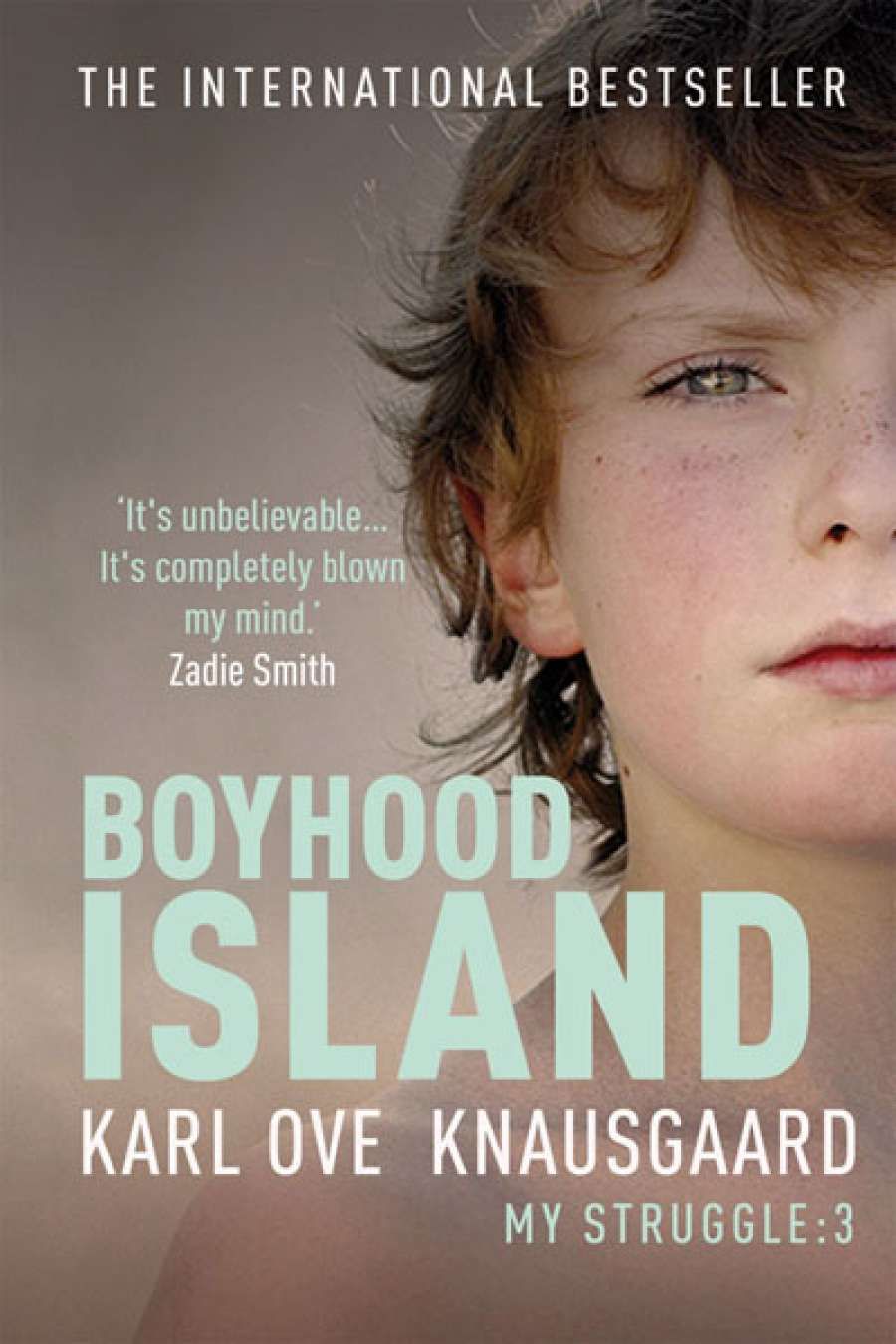

In Boyhood Island, the third volume in Karl Ove Knausgaard’s internationally acclaimed My Struggle cycle, we are taken back to where the series began: an island in southern Norway, seven-year-old Karl Ove and his older brother Yngve live under the tyranny of a cruel and taciturn father in the mid-1970s. Unlike the first volume, A Death in the Family (2012), which stays with young Karl Ove for only a few pages before casting off in many different directions, Boyhood Island follows him from ages seven to thirteen in a rarely broken, linear fashion. It ends neatly on the last day of class for the year, as Karl Ove’s family prepares to leave Tromoya, and he farewells a group of friends.

- Book 1 Title: Boyhood Island

- Book 1 Biblio: Vintage, $32.99 pb, 490 pp

For admirers of the first two volumes, all the joys of the serial novel are here: the re-entering of a familiar world, the re-acquaintance with beloved and detested characters, and the amplification of parts of a story you thought you already knew. But Boyhood Island is not quite just more of the same. While the first two books felt intrinsically linked, Boyhood Island is much closer to a conventional, stand-alone memoir, and could be easily enjoyed as such. The first pair felt free-ranging, formally daring, and baggy; this one is self-contained and deliberately bounded. No doubt this has a lot to do with the fact that Knausgaard wrote the first two volumes together and only began Boyhood Island once a plan for the whole series was devised.

If Boyhood Island seems more conventional, it might also be because many of the features of Knausgaard’s style in My Struggle feel more at home, or less radical, when applied to the world of the pre-pubescent. His obsessive attention to detail, especially around sensation and the material world; his predilection for long digressions on topics seemingly unrelated to the narrative thrust; and his brutally honest confessional tone – none of this feels as unusual here. It may be that by the third volume we have grown accustomed to this sort of narrative tic, but when he decides to spend several pages listing the names of all the sweets in the store and relaying the various conversations he had about how some of their flavours didn’t match their colour, it feels like an appropriate digression in a novel dedicated to capturing what life at eight was really like. Of course, Knausgaardians will know he does this sort of thing all the way through the novels set in his twenties and thirties too.

Describing your immediate surroundings in great detail also makes sense when they comprise your whole world. On this score, Boyhood Island might be the purest of the volumes so far translated into English. It allows Knausgaard to fully indulge his facility for evoking, with Proustian rapture, every nuance of experience and sensation.

Karl Ove Knausgaard, 2011

Karl Ove Knausgaard, 2011

The ecstasies and agonies to which Knausgaard is prone are given full expression in Boyhood Island. In the boy we recognise the overwrought man we met in the first volumes. He rhapsodises about all sorts of things. His driveway (‘oh, that alone, the driveways of childhood!’); the hot showers in the locker room (‘Oh how wonderful it was to stand under the hot water as the room slowly filled with steam!’); and his humiliations, often involving girls, are as excruciating as ever.

Because this book revisits his childhood, we crave answers to certain questions. Foremost among these must be how cruel his father really was (in A Death in the Family, we experience him more often as a fearful presence than an actual abuser), and why Knausgaard’s mother stayed with him so long, especially if she had any inkling how terrorised her children were. Knausgaard clearly never asked her: ‘She made a decision: she stayed with him, she must have had her reasons.’ As to the former, any doubts about the nature or extent of his father’s cruelty are well and truly dispelled.

In a telling passage – one of the few breaks in the narrative – Knausgaard pauses to wonder why his mother is such a hazy figure in his memory of those years. She was certainly the most important person in his life: ‘If there was someone there, at the bottom of the well that is my childhood, it was her, my mother, mum.’ The answer seems to be that his father looms so large in these memories that his mother is reduced from a person to a feeling of safety.

In recent interviews, Knausgaard has claimed that the controversy surrounding the publication of the first two books in Norway meant that the subsequent volumes suffered from a fear of repercussions. There is no sense in Boyhood Island of a retreat from the honesty that characterised the first volumes – neither in regards to his father, nor himself. This makes Boyhood Island something of a schizophrenic book, one where all the unfolding joys of childhood are interposed by moments of almost unbearable dread.

Readers have responded so strongly to these novels because, in their looseness, their abandonment of so many of the rules of good novelistic ‘craft’, they seem to render life more fully. In his struggles they see their own. A slightly more conventional rendering it may be, but Boyhood Island doesn’t disappoint.

Comments powered by CComment