- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Economics

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: An intellectual biography of a prolific theorist

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Albert O. Hirschman (1915–2012) was a development economist and political theorist whose work is essential reading for anyone interested in understanding how economic life figures in the political worlds we inhabit and the ways in which we give meaning to our lives in market-based societies. Perhaps best known for the distinction between ‘exit’ and ‘voice’, Hirschman was a prolific theorist who wrote about the role individual moral virtue and individual self-interest should play in economic activity, how economic growth in the developing world might best be achieved, and the reactionary rhetoric of neo-conservative politicians in the late 1980s, to list but some of the areas he covered. Hirschman’s writing was elegant; further, he understood the importance of the well-chosen word. He was, as this new biography by Jeremy Adelman shows, an economist for whom the essays of Montaigne were as important as the writings of Ricardo and Smith.

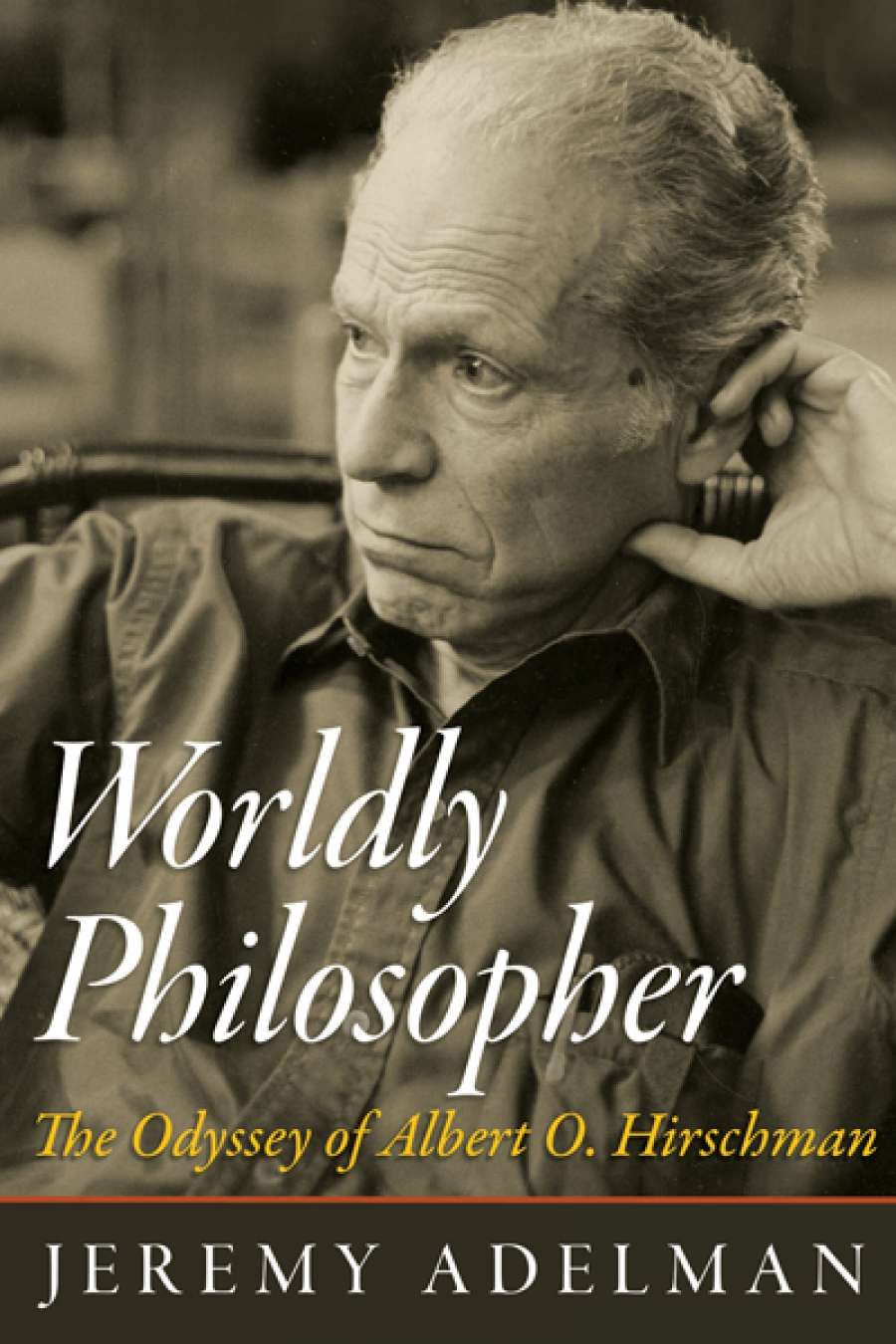

- Book 1 Title: Worldly Philosopher

- Book 1 Subtitle: The odyssey of Albert O. Hirschman

- Book 1 Biblio: Princeton University Press (Footprint Books), $74 hb, 754 pp

- Book 2 Title: The Essential Hirschman

- Book 2 Biblio: Princeton University Press (Footprint Books), $47.95 hb, 401 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 2 Cover Path (no longer required): /images/September_2014/The%20Essential%20Hirschman%20-%20colour.jpg

The publication of Adelman’s biography Worldly Philosopher will undoubtedly lead to far greater awareness of Hirschman’s work and of the rich life that he led. Adelman, who was a colleague of Hirschman’s at Princeton University’s Institute of Advanced Studies, had largely unfettered access to his unpublished manuscripts, private letters, and other works, as well as to close friends and family. This is an intellectual biography that provides a detailed insight into not only the life and ideas of one of the twentieth century’s most significant social scientists, but that also takes us on a journey back to the intellectual and cultural milieu of Germany between the wars. It is written in a wonderfully engaging style and, although it is nearly 800 pages in total, Adelman’s skill as a storyteller – and the interest of the subject matter itself – is such that reading this book is a delight rather than a chore. Adelman is also the editor of The Essential Hirschman,which contains both scholarly papers and excerpts from many of his best-loved books, and provides an excellent overview of Hirschman’s ideas.

Worldly Philosopher begins with Hirschman’s childhood in Berlin during World War I and its aftermath. Raised in an upper-middle-class family – his father was a surgeon – Hirschman’s early years were typical of many during the time. His parents were secular Jews who spent much energy in assimilating so as to ensure they were regarded as good German citizens. Hirschman was intellectually precocious and politically active and, with his beloved sister Ursula, soon fell in with the popular socialist and Marxist youth movements of the time. However, the rise of Nazism in Germany saw the left destroyed. In 1933 Hirschman fled to France where he studied economics. He fought for three months on the Republican side in the Spanish Civil War. The experience left him deeply sceptical of communism and the left in general.

Hirschman subsequently moved to Italy where he received his doctorate in 1938 from the University of Trieste on the devaluation of the French franc. With the war looming, Hirschman decamped to Paris. There he acquired a false French passport in the name of ‘Albert Hermant’ and fought with the French in their ill-fated campaign against the Nazi invaders.

In 1940, Hirschman met the classicist Varian Fry, who, with funds from the United States, enlisted the young German to work for the Emergency Rescue Committee (ERC), whose goal was to assist in the exodus of ‘at-risk’ intellectuals from Europe. Operating clandestinely in occupied France, the ERC assisted two thousand refugees who were thereby able to escape to the United States via Spain. The list of those saved includes Hannah Arendt, André Breton, Marc Chagall, Max Ernst, and Marcel Duchamp. In 1941, Hirschman fled to the United States, where he worked initially at a research centre in California and then enlisted in the US Army. At the war’s end, he was the translator at the first of the Nuremburg trials and had a unique vista on the retribution handed out to the surviving Nazi leaders.

After the war – and despite his excellent academic credentials – Hirschman had difficulty finding steady work. (Unbeknown to him at the time, this was largely a consequence of his political activity in the 1930s.) Making the most of what was a difficult situation, and with a young family to support, in 1952 Hirschman moved to Colombia, where he worked as a government economic adviser for most of the decade and published articles on development in the Third World. It was here that he wrote his classic work, The Strategy of Economic Development (1958), whichargued against the orthodoxy that development must be ‘balanced’ in the sense of ensuring that all parts of the economy grow at the same time. Latin America and its economic progress were to remain one of Hirschman’s lifelong passions.

In the 1960s, Hirschman returned to the United States where he was to spend the rest of his life. It was there that his academic career truly flourished. He worked with major intellectual figures such as Clifford Geertz, Donald Winch, and John Rawls and published a series of ground-breaking books, including Exit, Voice and Loyalty (1970), The Passions and the Interests: Political Arguments for Capitalism before its Triumph (1970), and The Rhetoric of Reaction (1991). He was fêted in intellectual circles, and the last years of his academic career were filled with academic honours, although one – the Nobel Prize – was to elude him, perhaps because of his unorthodox approach to economic analysis.

Albert Hirschman, Stanford, 1969 (photograph courtesy of Katia Salomon)

Albert Hirschman, Stanford, 1969 (photograph courtesy of Katia Salomon)

Hirschman was not an economist who thought our motivations could be understood solely in terms of utility maximisation. Nor did he think that the market was the only legitimate form of social organisation. In Exit, Voice and Loyalty, he argues that within the market ‘exit’ is the only option one has to respond to policies with which one disagrees, whereas in democratic systems one has the option of ‘voice’ such that those in power are systemically required to take into account the criticisms and concerns of their citizens. In The Passions and the Interests, Hirschman defends the controversial anti-Weberian thesis that rather than being a product of the Protestant ethic, the emergence of capitalism was due to the influence of a group of thinkers who argued that the best way to prevent social chaos was to channel the passions and interests of the people into money-making. My personal favourite is the essay ‘Against Parsimony’, wherein Hirschman explores the thought that we should minimise the reliance on human virtue in our institutional design. What unites all of these writings is the importance he accords to maintaining, in our economic and political theory, a sense of the complexity of human nature.

I have one minor concern with this book. To my mind, it does not provide a clear explanation as to how Hirschman arrived at his very distinctive views. In his early years Hirschman read Marx, and his subsequent political experiences led him to reject communist solutions and, indeed, any form of political theory that promised a complete solution on how to organise social life. But that does not really explain why he was attracted to economic theory itself or the kind of economic theory he did develop. Moreover, it is difficult to know exactly where Hirschman stood on the use of market-based solutions to social problems. The failure to explore more fully the origins of Hirschman’s unique political views is one notable weakness of the book.

In the overall scheme, however, these are very negligible concerns. Worldly Philosopher is an outstanding literary achievement that provides insight into the life of one of the twentieth century’s most important social scientists. Jeremy Adelman tells his story in an entertaining and compelling style. In conjunction with The Essential Hirschman, it should go some way toward ensuring that Hirschman’s ideas continue to be discussed throughout the twenty-first century.

Comments powered by CComment