- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Shadow King

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Wilhelm II, German Kaiser and King of Prussia, may be a shadowy figure for Australian readers, better known as the butt of funny-scary caricatures in British World War I propaganda or of black humour in popular soldiers’ songs, than as a political player in his own right. He remains enigmatic even for scholars. Some hand him the burden of responsibility for World War I, despite the immediate trigger being the military standoff between two other states altogether, Austro-Hungary and Serbia. Others see him as an incompetent figurehead who merely rubberstamped the territorial ambitions of the German military.

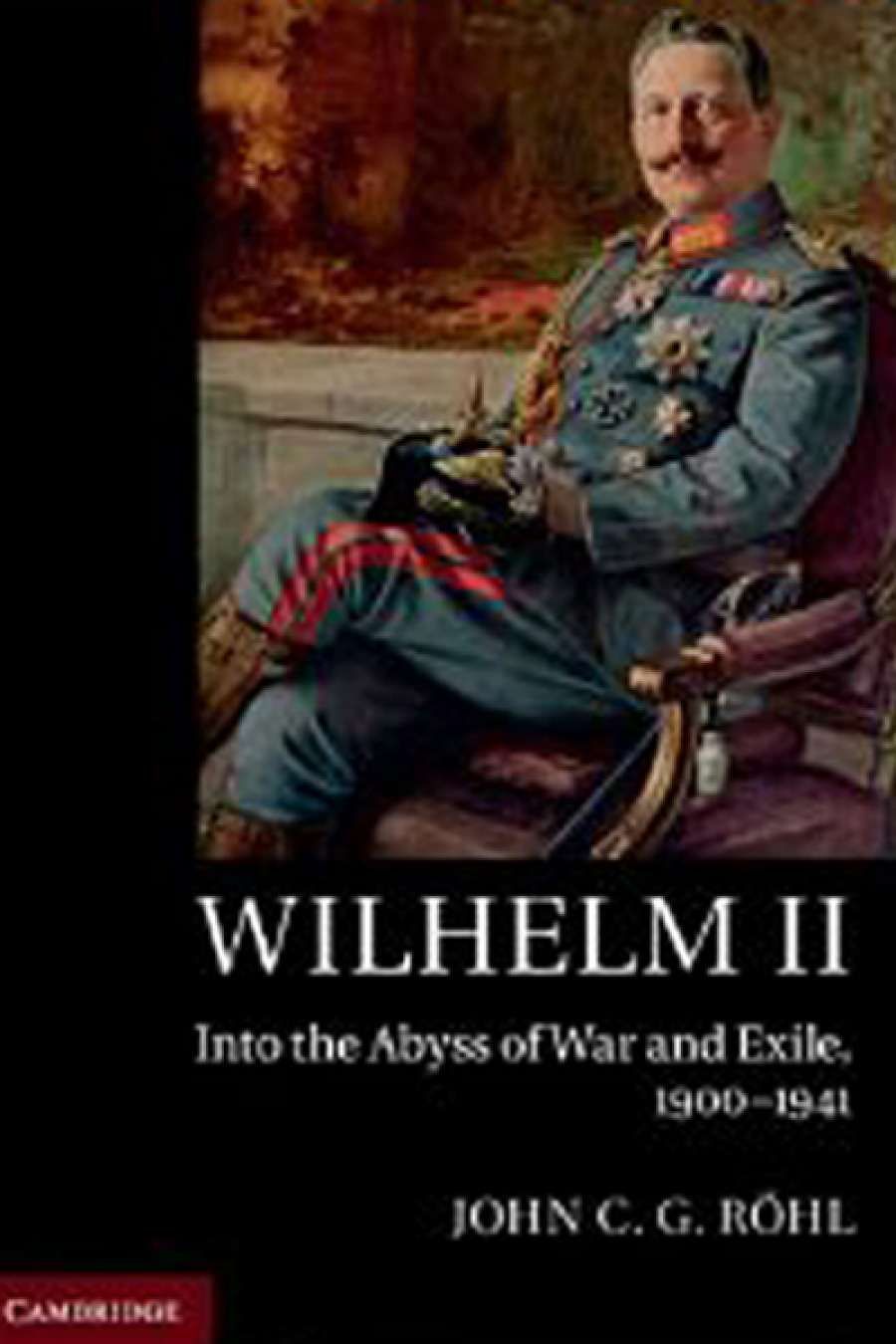

- Book 1 Title: Wilhelm II

- Book 1 Subtitle: Into the abyss of war and exile, 1900–1941

- Book 1 Biblio: Cambridge University Press, $87.95 hb, 1562 pp

He was also viscerally anti-Semitic, anti-Catholic, anti-Slav, and anti the French, those duplicitous Catholic Latins who had set off the whole ghastly descent into democracy with their regicidal revolution. Mind you, his international ambitions made for some strange bedfellows. The Slavic Russians and Serbs were abhorrent, but the Bulgarians were courted as allies; the Semitic Jews who ran international finance and plotted world domination (Wilhelm was a great admirer of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion) were to be destroyed in a proto-Nazi fantasy, but the equally Semitic Arabs were to be helped to raise a new caliphate to fight valiantly alongside the Germans. While the Anglo-Saxon English were not fellow-Aryans but a vulgar nation of shopkeepers, the Catholic Austrians were trusted fellow-Germans and allies.

Nine sovereigns at Windsor for the funeral of King Edward VII in 1910. Wilhelm II (centre), stands behind George V (photograph by W. & D. Downey)

Nine sovereigns at Windsor for the funeral of King Edward VII in 1910. Wilhelm II (centre), stands behind George V (photograph by W. & D. Downey)

George V, Wilhelm’s first cousin, wrote a savage letter on November 1918, the day Wilhelm went into exile, describing the results of Wilhelm’s megalomania. ‘He has been Emperor just over 30 years, he did great things for his country but his ambition was so great that he wished to dominate the world & created his military machine for that object,’ George wrote. ‘Now he has utterly ruined his country & himself & I look upon him as the greatest criminal known for having plunged the world into this ghastly war which has lasted over 4 years & 3 months with all its misery.’

Rohl opens this book with Wilhelm’s visit to his dying grandmother, Queen Victoria. His modest demeanour and the loving gestures of assistance he rendered Victoria on her deathbed surprised and impressed his English relatives. Once home, he reverted to the personality quirks that not only usually irritated his extended family, but made him an unpredictable and irascible leader. The following forty chapters deal with Germany’s place in the Great Power manoeuvring on the continent and in North Africa and the Middle East that led up to World War I, always centred on Wilhelm’s role. Rohl’s research is meticulous and the minutiae can be eye-opening: illuminating Wilhelm’s plans for Turkish and Arab cooperation, for example, the débâcle of Austro-Hungary’s response to the assassination of Franz Ferdinand and the acceleration of mobilisation across the continent that ensued, and Wilhelm’s vacillation, as wild as mood swings, between east and west, Russia and France, as the primary target of his military ambitions. The war itself, and Wilhelm’s exile and death, are swiftly wrapped up in the final six chapters.

Swamped as we have been with writing about World War I this anniversary year, there is no need to reprise a general outline of events. But Rohl’s research provides an interesting counterpoint to the Anglophone view. With a German father and English mother (like his subject), Rohl grew up bilingual and, though he made his career in Britain, has spent a lifetime examining German archives. German, as well as non-German, historians have struggled with interpretations of World War I and its aftermath ever since the general armistice was signed at Compiègne on 11 November 1918, especially after the horror of World War II. There have been periods of highly controversial revisionism in Germany along the way. Was Germany responsible for the slaughter, or was it just one of the Great Powers furiously jostling for dominance across the continent and beyond to the non-European countries they were brutally and rapaciously annexing? Did the unprecedentedly punitive terms of the Versailles Treaty set up the conditions for the rise of National Socialism?

‘Rohl’s research provides an interesting counterpoint to the Anglophone view.’

Barbara Tuchman’s famous book The Guns of August (1962) has all of Europe blundering inexorably towards war and ignores, presumably as trivial, the stand-off between Austro-Hungary and Serbia. Sean McMeekin’s book The Russian Origins of the First World War (2011) – the title says it all – was highly controversial. Thomas Lacquer, in a review of Christopher Clark’s fascinating book, The Sleepwalkers: How Europe Went to War in 1914 (a title which echoes Tuchman’s view), quotes Tocqueville on the French Revolution: ‘Never was any such event, stemming from factors so far back in the past, so inevitable and yet so completely unforeseen.’ And yet World War I was not only foreseen, it was avidly wished for in many quarters – not only as a fight for territory but as a culturally cleansing event. What was unforeseen was the grinding length and the astounding death toll. From that grew the desire for criminal sanctions, a new view of war in moral rather than purely strategic terms, which completely undid the Westphalian system and opened the way for the concept of total war.

Rohl’s book doesn’t answer these pressing questions, because it is so intriguingly centred on the person of Wilhelm II. He tells us, for instance, how angrily the French press reacted to an action of Wilhelm’s, but not what they said, so how can we form an opinion about who might have been right? He tells us at length about British foreign secretary Edward Grey’s recorded responses to conversations with the German ambassador and correspondence with the German chancellor, but does not illuminate the British context. We are fully aware of the thinking, the feints and parries coming out of Berlin, but blind to the context and intentions of other players.

The unicorn in winter: ‘Our Kaiser in the field’

The unicorn in winter: ‘Our Kaiser in the field’

This does give us an interesting corrective to Anglophone accounts, but dashes hopes of, for example, clarifying whether the victorious allies were right to hold Wilhelm personally responsible for the war and to prosecute him under newly invented international sanctions. Rohl mentions how the Europeans were keen to press on with a trial, how the Americans urged caution, but doesn’t discuss the vital ramifications, and the narrative strand trails off in the refusal of Queen Wilhelmina to allow him to be extradited from the neutral Nether-lands, where he had sought asylum. The only matter on which Rohl expresses an unequivocal opinion is the vileness of Wilhelm’s racial beliefs.

This final instalment of Rohl’s trilogy is exhausting as well as exhaustive – more than 1500 pages, including 268 pages of detailed notes and a 59-page index – and those who are reading out of interest, rather than for purpose of study or review, will doubtless fast-forward through some of the more stupefyingly detailed bits. But those interested in the era, European history, the history of World War I, and German history in particular will find it endlessly fascinating.

Comments powered by CComment