- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Commentary

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The novel begins with the burnished quality of something handed down through generations, its opening lines like the first breath of a myth. Seductive in tone and concision, charged with an aura of enchantment, the early paragraphs of George Johnston’s My Brother Jack (1964) do more than merely lure the reader into the narrative. In these sentences, Johnston reveals the conviction and control of a master storyteller who, at the outset, establishes his ambition and literary lineage:

In the voice of the novel’s narrator and Johnston’s alter ego, David Meredith, we hear the tone and grand-scale wager of another coming-of-age tale published more than a century before. As Dickens writes in David Copperfield, ‘Whether I shall turn out to be the hero of my own life, or whether that station will be held by anybody else, these pages must show.’ My Brother Jack opens with a similar ambition. Taking the reader to the ground level of outhouses and along the ‘damp autumn pavement’ of suburban Melbourne, Johnston establishes his ability to draw allusions that allow us to apprehend the urgency of a tale that examines Australian archetypes through the disparate characters at its core.

Jack and David Meredith, brothers growing up in Melbourne between the world wars, form two versions of the Australian psyche. From the beginning, Johnston contrasts Jack – ‘wild and adventurous and reckless’, a representative of the Aussie battler – with the younger, introspective David. Like Nick Carraway in The Great Gatsby and Ishmael in Moby-Dick, Meredith is at once an observer and a participant in the story he relates.

Fifty years after its first publication, My Brother Jack reminds us of the beginning of L.P. Hartley’s The Go-Between: ‘The past is a foreign country: they do things differently there.’ Indeed, today’s readers discover in the pages of My Brother Jack a world at once familiar, geographically speaking, and yet, due to the details of its era, just beyond our grasp.

Nonetheless, the novel is essential literature for understanding a time in Australia when children navigated their lives, as Johnston writes, through the ‘mess to be cleaned up in those years of 1919 and 1920, after the war and the Spanish influenza: the bodies of the dead to be located and the great cemeteries set up, and all those military hospitals in France and Flanders and Britain and Italy to be cleaned out of colonial troops so that there would be space in which to try to heal the indigenous maimed’. Johnston describes a period replete with visions of amputees and the ‘clutter of walking-sticks’. These memories haunt Meredith much as they haunted his creator, a prolific writer of journalism and fiction whose own persona has melded into the national literary consciousness.

‘Today’s readers discover in the pages of ‘‘My Brother Jack’’ a world at once familiar, geographically speaking, and yet, due to the details of its era, just beyond our grasp.’

Nicholas Birns, editor of Antipodes: A Global Journal of Australian/New Zealand Literature, suggests that contemporary readers’ temporal distance from these events provides a key to the novel’s lingering relevance. ‘I think the more My Brother Jack and the rest of the trilogy seems of a different era, not the near past but the further past, the more interesting and less obvious we will find it,’ he says.

By the time he began My Brother Jack, Johnston had been living as an expatriate for more than a decade, most of it on the Greek island of Hydra. The highlights of his life are well known. Born in Melbourne in 1912, Johnston became Australia’s first accredited war correspondent. During World War II, his dispatches appeared in the Argus, the Sydney Morning Herald, the Adelaide Advertiser, and, as the war progressed, the London Daily Telegraph, Time, and LIFE magazines, revealed an urgent honesty coupled with an ability to capture, in the confused midst of conflict, the essential human detail, as when he wrote in his New Guinea Diary (1943):

It’s difficult to really know what is going on. Today I was in the front line attempting to get a picture of what was happening on the Sanananda track. The soldiers asked me how the fighting was going and I asked them, and neither party gathered very much information. In this sort of country you can see very little beyond the ten or twenty feet of black-shadowed jungle that lies immediately ahead. Going up, I met a kid who looked young enough to be suspected of playing truant from school – coming back from the Gona front for medical attention to an arm that had been badly chewed by a mortar bomb. We stopped to yarn and he handed me his water bottle.

‘Taste that,’ he said, with a grin, and I did, and promptly spat it out.

‘Salt water,’ he said. ‘That’s just to show ’em that I got to the sea on the north coast – and I walked all the way!’

In George Johnston: A Biography (1986), Garry Kinnane writes of Johnston’s disillusionment with his role as a correspondent: ‘He had always felt that the very situation of the war correspondent was parasitical, and that the only authentic roles in war were the soldier’s and the victim’s.’ Here, in My Brother Jack, Johnston describes the experience from Meredith’s perspective: ‘I wrote copiously and I wrote brilliantly … and I skulked and dodged and I was desperately afraid, and I wrote myself into my own lie, the lie I had to create …’ Out of this process, and with the aid of Charmian Clift, whom he met near the end of the war and married in 1947, Johnston forged his own myths – both private and national – in the novels known as the Meredith trilogy.

Coming upon My Brother Jack on its fiftieth anniversary, a reader may be forgiven for assuming that Johnston sprang fully formed as a novelist with the first book in the trilogy. His background as a journalist taught him to work quickly and under the pressure of deadlines. Along with memories of him ‘hammering away’ at his typewriter, friends and colleagues spoke of his great storytelling abilities, a talent which he honed in the numerous books – the majority of them now out of print – which he published before My Brother Jack. These include thirteen works of non-fiction and fiction published under his own name, among them Australia at War (1942) and Skyscrapers in the Mist (1946); five under the pseudonym Shane Martin; and three in collaboration with Clift, notably High Valley (1949), which won the Sydney Morning Herald Literary Competition for an unpublished novel. In Charmian and George (2004), Johnston’s Argus and Australasian Post colleague Max Brown relays the love affair of a couple who, due to their tempestuous private lives and competitive professional relationship, have often been called Australia’s variation of F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald. While Kinnane links Johnston’s years as a correspondent with his decision to write the Meredith trilogy in order to ‘expose that particular George Johnston he had once been, and to annihilate him’, Brown credits the influence of Clift. After seeing her husband write a string of workmanlike novels that failed, in her opinion, to pierce the surface, she urged him to write ‘something worthwhile’. Brown writes, ‘She said she had always considered him more interesting than the people he invented. And so George’s work took a significant swing to the genre that was to produce the Meredith trilogy.’

Published four years before My Brother Jack and an early attempt at capturing his own experience in the persona of Meredith, Closer to the Sun (1960) gives readers a glimpse of the character who, much like Johnston, ‘smoked too heavily, lived too nervously and travelled too hard and too far …’ From this point on, Johnston grew determined to work on a more ambitious scale. As Kinnane writes, ‘Although it began as an exercise in memory, prompted by intense nostalgia, My Brother Jack, as it developed, soon became a much more analytical quest than these terms would suggest, and the subject of analysis was his own character.’ Investigating that character, forged in Melbourne in a generation that came of age during the Depression and World War II – a time when his future and identity, much like the country itself, remained uncertain – became his focus.

George Johnston approximately 1965 / Australian News and Information Bureau (credit: National Library of Australia)

George Johnston approximately 1965 / Australian News and Information Bureau (credit: National Library of Australia)

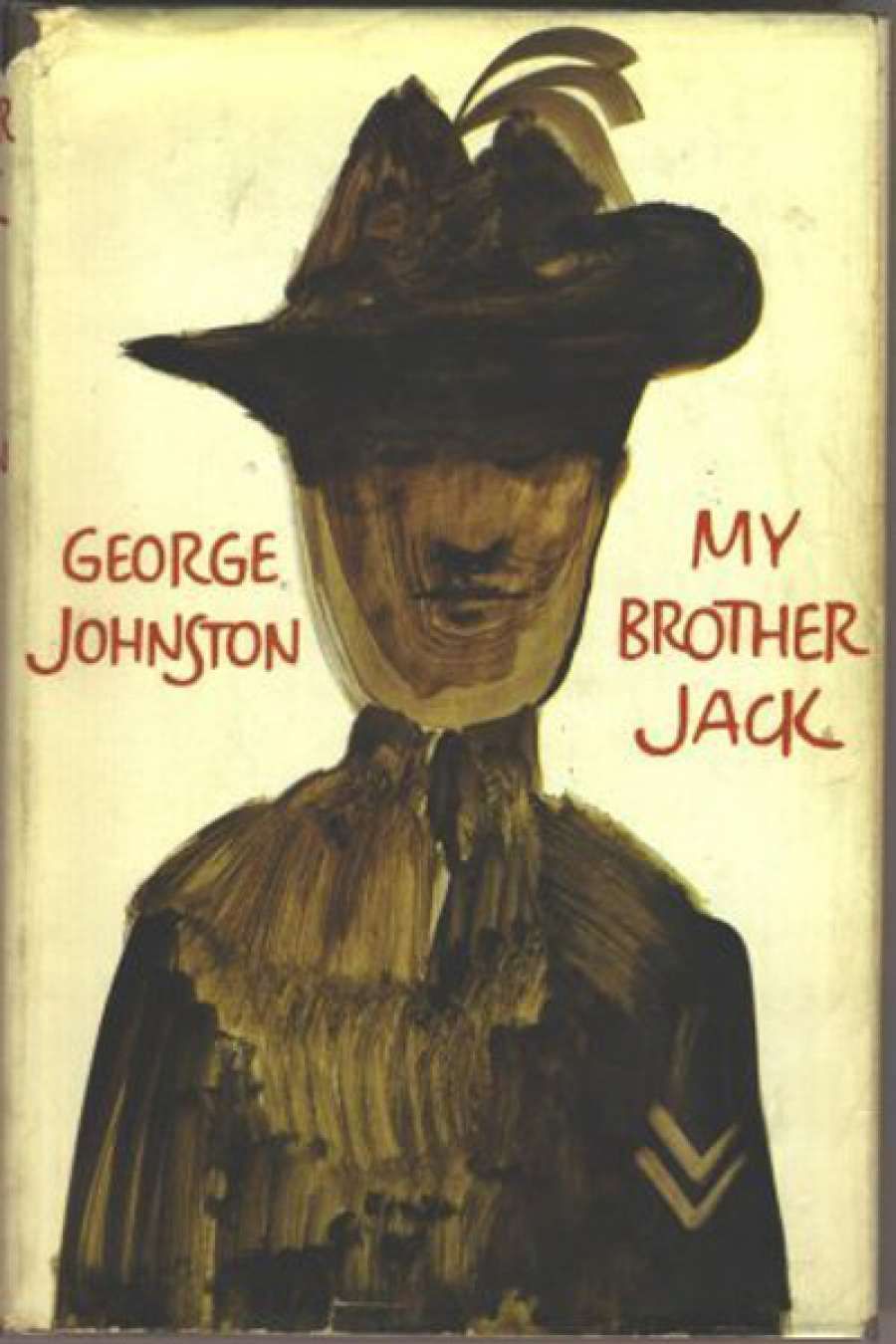

In January 1963, shortly after he commenced My Brother Jack, Johnston wrote to his first wife, Elsie: ‘[I]f I can pull off what I am doing I think it might make everything worthwhile.’ The process nearly killed him. He finished the novel in June and, as Kinnane writes, suffered from such exhaustion that he checked into an Athens hospital. Upon his release six weeks later, Johnston received positive news from his publisher, Collins. With a large-scale publicity campaign planned, including jacket art by his friend Sidney Nolan, upon whom he later based the character Tom Kiernan in Clean Straw for Nothing (1969), Johnston returned to Australia for the novel’s release to find Collins’s pithy advertisement: ‘The Great English Novel went out with Dickens. The Great American Novel is announced at least once a week. But here is a Great Australian Novel.’

With such attention, and exotic after his years abroad, Johnston proved expert in stoking the flames of his public persona. In an interview with Women’s Weekly, he described his work on the novel: ‘One day I was alone in the house and very sick. I thought I was going to die. I thought of the books I had written and felt that not one of them amounted to anything. I got out of bed, still sick, and I went downstairs shaking with fever and wrote the first page of My Brother Jack exactly as it was printed.’ To another interviewer, he said, ‘I worked eight hours a day for seven days a week on My Brother Jack, never taking a day off until I had finished 125,000 words.’

In his final years, the vintage of a fertile career, Johnston wrote the two other novels that form his Meredith trilogy. Like My Brother Jack before it, Clean Straw for Nothing received the Miles Franklin Award. Differing markedly in subject and structure, Clean Straw for Nothing reintroduces Meredith’s seductive voice as, abandoning his successful career as a journalist to write novels, he guides us through a narrative that shifts in time and setting from, among other places, Melbourne in the mid-1940s to Sydney and Athens in the 1960s. The final novel in the trilogy, A Cartload of Clay (1971), remained unfinished at the time of Johnston’s death, aged fifty-eight, on 22 July 1970.

In a questionnaire for the Age Literary Supplement, Johnston said that he spent seventeen years thinking about the Meredith trilogy. Writing for the Bulletin in 1971, Nancy Keesing found in the trilogy a representation of an entire generation of Australians brought up during World War I, about whom, she wrote, ‘Many retain insecurities even in success … Their manner, too, seems more distinctively Australian than that of their immediate predecessors or their present juniors. They are represented by numerous thinly disguised characters in Johnston’s trilogy.’

Five decades after its publication, My Brother Jack continues to speak to writers, readers, and critics. Geordie Williamson, chief literary critic for The Australian and author of The Burning Library: Our Great Novelists Lost and Found (2012), says he discovered in Meredith’s voice the ‘air of wounded adolescent melancholy’:

If you are one of those who prefers their literature plainspoken – documentary-style realism, in other words – then I think it is certainly one of the great Australian examples, a work of which Zola or Orwell would be proud … A real and rare human honesty rescues the work from its flaws.

Williamson deems My Brother Jack and Hal Porter’s Watcher on the Cast-Iron Balcony as ‘impeccable documents of the period’. About Johnston’s lingering influence, he says:

You hear his voice in Robert Drewe’s autobiographically inflected work, with its intelligence balanced against blokey wit, for example; and in those works by Helen Garner that make a fetish of tough truths. You could say that Malcolm Knox or Andrew McGahan have at times followed in Johnston’s footsteps, whether consciously or not. But it’s beyond doubt (to me, at least) that My Brother Jack was a model for Clive James when it came to that other great postwar quasi-fiction, Unreliable Memoirs.

Nicholas Birns, who lives in New York City, says that he first encountered Johnston’s fiction in the stacks of the Columbia University library. ‘My first reaction to My Brother Jack was that it was structurally similar to such modernist books as The Great Gatsby or Heart of Darkness, with the elegiac onlooker describing the man of action.’ In contemporary Australian fiction, Birns sees Johnston’s influence in the work of Roger McDonald and Steven Herrick and compares his work – ‘concerned with masculinity in ways male writers have not been before or since’ – to that of the American novelists John Steinbeck and Robert Penn Warren.

Two ambitious contemporary Australian novels, both of which deserve revisiting, pay homage to Johnston’s work and life with Clift. Patricia Cornelius’s My Sister Jill (2002) subverts Johnston’s masculine-dominated world to focus on the daughter of a former prisoner of war in Burma. Cornelius, who received the 2014 Victorian Premier’s Award for Drama, says, ‘The legacy of the war was an important aspect for my book, in which the family inherits the same territory that Johnston was exploring. I knew that I wasn’t really looking to imitate [Johnston’s] style, but I wanted to absolutely go into the family life the way he goes into the family.’ The opening passage of Susan Johnson’s The Broken Book (2004) echoes, nearly word for word, that of Clean Straw for Nothing. The life of Johnson’s heroine, Katherine Elgin, closely resembles Clift’s, but the novel’s fragmented structure owes its debt to Clean Straw for Nothing.

James Joyce wrote Ulysses not only as an attempt to add to the dialogue about the art of the novel but, as Colm Tóibín said during his 2004 visit to Australia, to take on the world. With similar ambitions, Johnston offered My Brother Jack as his gamble for the Great Australian Novel, a work omnivorous in its hunger to examine a time, place, and people. Fifty years on, the novel remains a watermark for the nation’s literature.

Comments powered by CComment