- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Blog

- Custom Article Title: Portraiture by stealth

- Non-review Thumbnail:

I had my portrait done by stealth the other day. Throughout the innocent chatter of a dinner party, while I artlessly revealed my double chin and paraded my characterful nose, fellow guest and Melbourne art bandit W.H. Chong was scribbling away on his smart phone. I just thought he’d got bored and was playing Angry Birds.

I should have realised; as well as being Text Publishing’s illustrious graphic designer – and creating many covers for ABR over the years – Chong is known for his portraits of creative types (and I have to use that term loosely in order to include myself in some rather august company).

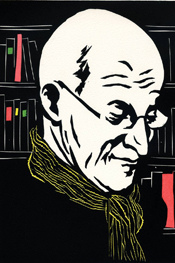

The Green Room walls of Melbourne’s Wheeler Centre are lined with his works, including novelist Lloyd Jones, writer and broadcaster Ramona Koval, crime fiction writer Peter Temple, sports commentator and writer Peter Meares, and critic, poet, and children’s fantasy writer Alison Croggon. A portrait of singer/songwriter Paul Kelly hangs in the ABR offices, along with those of David Malouf and Patrick White.

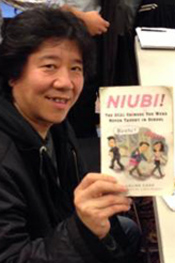

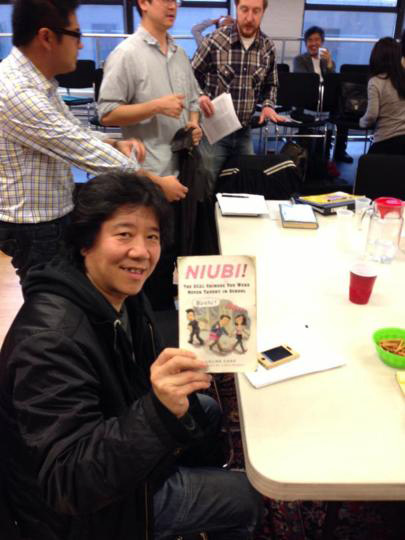

W.H. Chong and his portrait of Paul Kelly

W.H. Chong and his portrait of Paul Kelly

Several of his notebook portraits are also featured in a recently opened exhibition that he has co-curated at St Kilda’s Brightspace Gallery with fellow artist Konrad Winkler, called Double Vision.

I don’t think Chong has quite captured my elusive beauty, but I am reminded of Picasso’s response when someone criticised his portrait of Gertrude Stein and said that Stein didn’t look like that. Picasso said, ‘She will.’

I have been thinking a lot about portraiture myself recently, being in the early stages of planning a series for Radio National on this very topic. It is a collaboration with art historian Angus Trumble, the new director of the National Portrait Gallery.

You need someone with wit, passion, and eloquence when you are talking art on the radio, and Angus has it in abundance. He says he is interested in the ‘fleck of detail’ and small histories rather than grand narratives, but whatever their size, he has an amazing faculty for ferreting out the little-known but fascinating fact.

Although Melbourne born and raised, Angus has just spent eleven years at the Yale Center for British Art in New Haven, Connecticut, as senior curator of sculpture and painting. His publications include A Brief History of the Smile (2005); once you realise that showing one’s teeth was a sure sign of moral turpitude, madness, or the misguided enthusiasm of the nouveaux riches, you realise that rather than checking out the eyes, it is the lips in art that are the most revealing.

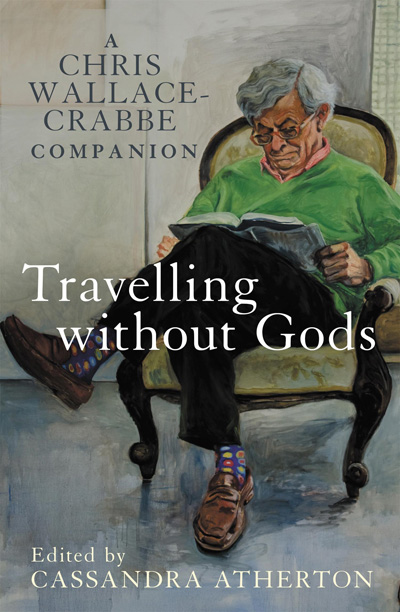

Of course not all portraits are visual; another luminary celebrating his eightieth birthday this year, the poet Chris Wallace-Crabbe, has had a festschrift compiled in his honour, Travelling without Gods, edited by Cassandra Atherton.

Among the many illustrious, witty, and eloquent contributions there is a poem by Seamus Heaney written not long before the latter’s death in August 2013. The festschrift, as the name suggests, is a German invention, commonly a series of celebratory essays from colleagues and former pupils. If you are violently opposed to flattery or your colleagues can’t get their act together, you might end up with a gedenkschrift, or memorial publication.

For carbon footprint excesses we have to turn, perhaps appropriately, to the festschrift compiled for the German classicist Joseph Vogt. Begun in 1972 on the occasion of his seventy-fifth birthday, it now stands at eighty-nine volumes.

Wallace-Crabbe’s festschrift is a mere 236 pages with index, but it is enough to give a flavour of his life’s work and singular contribution to letters.

The portrait on the cover of Travelling without Gods, a fine likeness, is by his partner, the artist Kristin Headlam.