- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Literary Studies

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Publishing without limits

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Great publishers seem to be scarcer than great writers, possibly because people grow up dreaming of being the next Hunter S. Thompson or Simone de Beauvoir rather than Sonny Mehta or Beatriz de Moura. Writers probably need publishers, but publishers definitely need writers. Such a fact has never seemed more tangible to me than as I read The Garden of Eros, John Calder’s account of the major literary events of his lifetime, which focuses on Maurice Girodias of Olympia Press, Barney Rosset of Grove Press, and Calder’s own Calder Publications. Between them they published dozens of the most important writers of the twentieth century: Marguerite Duras, Samuel Beckett, Vladimir Nabokov, Eugène Ionesco, Alexander Trocchi, William S. Burroughs, Claude Simon, Henry Miller … the list goes on. Calder himself published eighteen Nobel Prize winners.

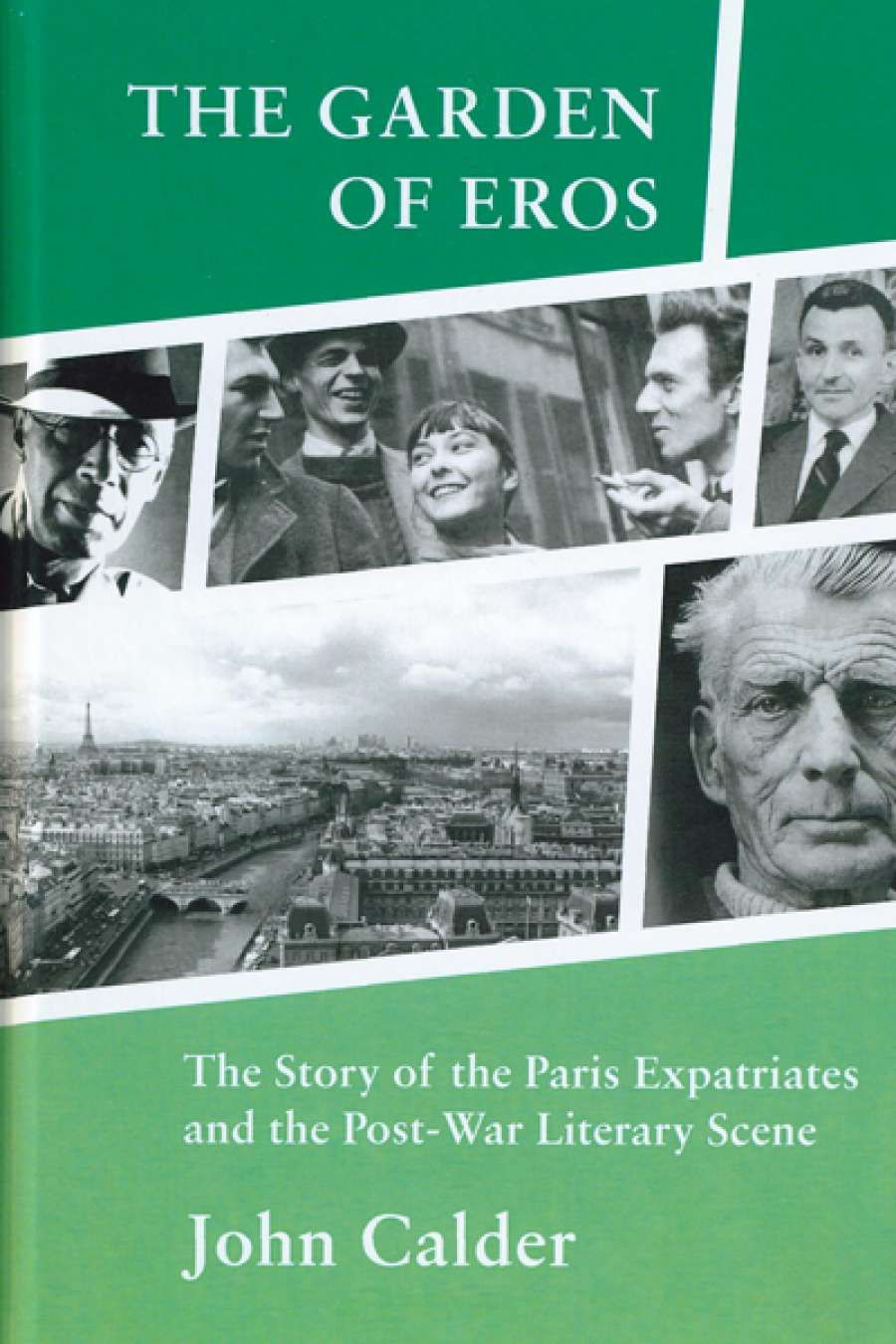

- Book 1 Title: The Garden of Eros

- Book 1 Biblio: Calder Publications, $49.95 pb, 360 pp, 9780957452206

How, then, do we evaluate a publisher’s accomplishments?Modern and contemporary writers are often regarded as types: the inward-looking Proustian; the polymath in the vein of Joyce or Foster Wallace; the show-don’t-tell realist descended from Hemingway or Carver. Is there such a system of classification for publishers? Calder’s book, written in modest, restrained prose, is helpful in this way: not only does it trace with great care the fortunes of these three publishers (who at one time formed something of a union), but it also offers a kind of survey of literary life in New York, Paris, and London, from the end of World War II to the late 1970s.

It would be difficult to overstate how central Calder was to twentieth-century literature. The Garden of Eros, however, isn’t a comprehensive history, but focuses on a handful of his more hedonistic and independent-minded associates. What at first seems like a slightly baroque title quickly comes to look like an understatement.

Calder’s main focus is on the progress of English-language publishing in Paris from 1945 to the early 1960s. His survey includes the formation and dissolution of the avant-garde magazine Merlin, the origins of The Paris Review, the role of Paris’s best English-language bookstores, and, most importantly, the fortunes of the subversive publishing house Olympia Press and the battles against censorship waged by its owner, Girodias. (The remainder of the book deals in turn with Barney Rosset’s New York, then Calder’s own London, though not in as much detail.)

Much of what transpired during this period, as Calder remembers it, was at least in part a reaction against the difficulties, the deprivations, and oppressions of Vichy France and the Nazi occupation. For Merlin, the magazine started by Trocchi, publishing translations of the Marquis de Sade was as important as publishing Beckett, Sartre, Ionesco, and Neruda. Much of what was published by Merlin was at least nominally banned, but, as Calder explains,

After so many years of German censorship, printers were not afraid of an occasional fine, while the climate amongst the intelligentsia was in favour of literary freedom, the right to know all and discover everything that had for so long been unavailable.

What’s more, radical manuscripts, which might otherwise have been printed in the United States, ended up in the hands of English-language publishers in Europe, thanks to McCarthy’s war against all things left-seeming. Publishing literature, in other words, both spiritually and circumstantially, meant publishing without limits.

Girodias and Trocchi – in many ways the guiding forces behind The Garden of Eros’s strongly anti-authoritarian and libertine spirit – published radically and subversively, and lived that way too. ‘Girodias was impassioned about censorship, about breaking down taboos, making the world randier, and about fighting the hypocrisy of the bien-pensant bourgeois world,’ writes Calder. ‘Later he was a radical anarchist, and the same can be said of Trocchi. A libertine personal life and political radicalism often go together, and with it a cavalier attitude towards women who exist for personal pleasure and use.’

There is a beautiful freedom and endless sense of renewal to Calder’s Paris. Even taking into account the more conventionalParis Review crowd, who lived more moderately and comfortably than their counterparts at Merlin, according to Calder, the city was wilder, hornier, and drunker than the other hotspots of subversive publishing that feature later in the book, such as New York and London. But there’s also an unpleasant sense of darkness to what is described, and it doesn’t come as a surprise when both Trocchi and Girodias end up burnt out and at a loss, although, it must be said, Girodias had accomplished significantly more than Trocchi in his efforts to fight censorship generally, and with the publication of books such as Lolita and Story of O specifically. But Girodias also never plumbed the same depths of addiction as his friend Trocchi, whose heroin habit lasted more than three decades.

The action shifts eventually to New York, before moving briefly on to London and Calder’s own operations (although Calder goes into considerable detail about Girodias and Rosset, his own private life is rarely discussed). Grove Press is the more familiar of the stories, and while Calder describes in great detail Rosset’s almost pathological need to challenge the authorities on matters of censorship, he doesn’t offer as complete or personal a portrait of Rosset as Neil Ortenberg and Daniel O’Connor did in their documentary Obscene (2008).

The Garden of Eros gives the impression that, rather than being more predictable and sensible, as might be assumed, publishers can at times be more contradictory or even mercurial than their authors. If the great test for an author is to be single-mindedly devoted to his or her work, the challenge for a publisher is to be all things to all people. Publishers need to have artistic or cultural credibility in order to gain the trust of authors, but also a mercenary streak, at least if they’re going to stay in business. (Of the dozen or so publishers described in The Garden of Eros, not one doesn’t seem to face bankruptcy at some point, and both Girodias and Rosset relied on the income from publishing erotica – There’s a Whip in My Valise was one of Olympia’s titles – to stay afloat.)

Above all, Calder’s book argues, publishers need to be alive to the ebb and flow of public life around them. The Garden of Eros is the ideal portrait of a generation of radical publishers. Calder brings to life the inspired madcap, no-rules cultural universe that this trio not only occupied, but helped to create.

Comments powered by CComment