- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Literary Studies

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Game of thrones

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

When Queen Victoria died she had ruled the British Empire for sixty-three years. In the same year as her ascent to the throne, the capital of the colony of Victoria was christened Melbourne, after her first prime minister. She died in 1901, soon after Federation. After her death, her real character remained largely unknown for decades (Lytton Strachey’s seminal biography was still twenty years hence). The public regarded Victoria as dour and was oblivious to her remarkable qualities. Any concern for her reputation was then lost beneath the carnage of two world wars and multiple mass conflicts. How this happened is the subject of Unsuitable for Publication.

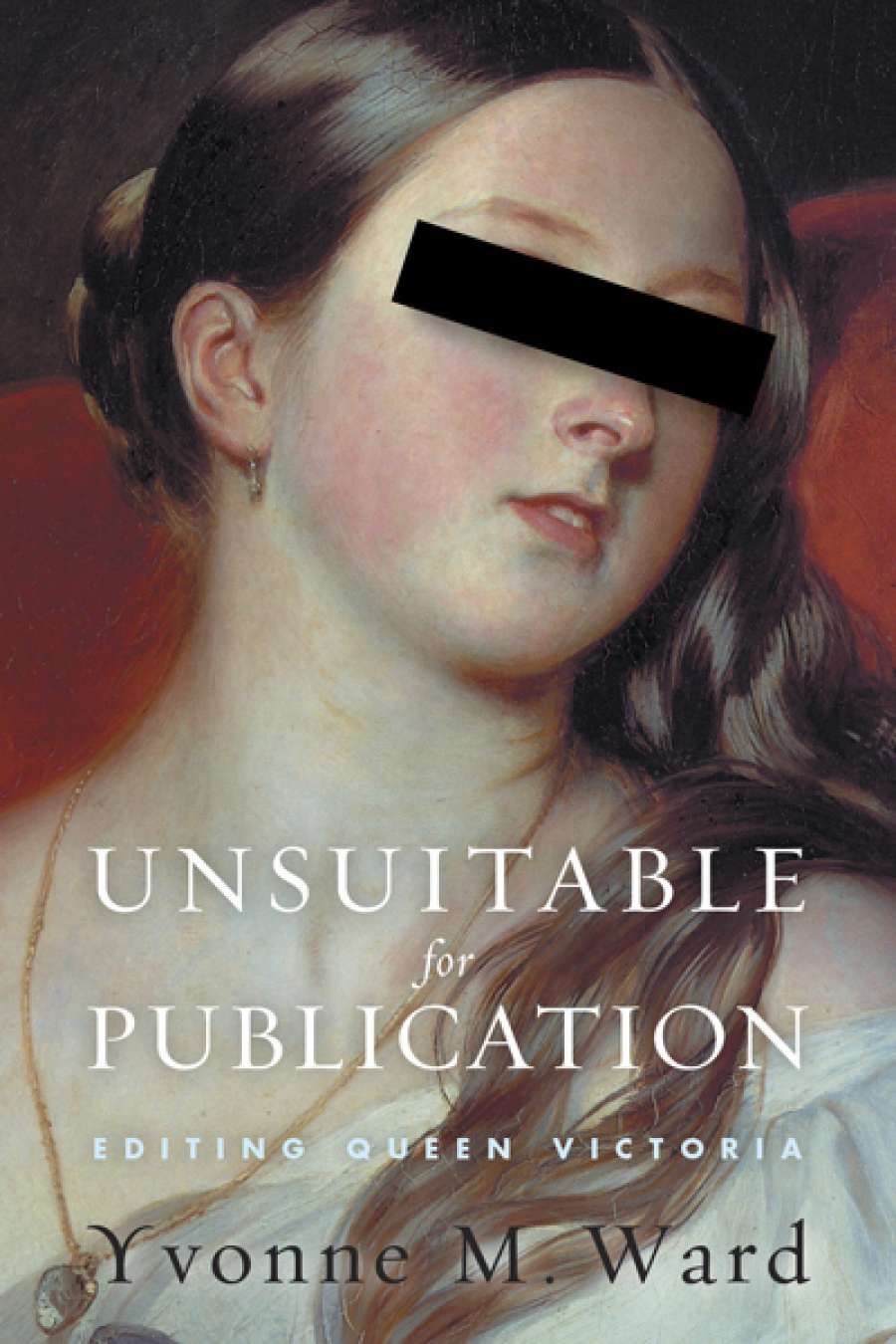

- Book 1 Title: Unsuitable for Publication

- Book 1 Subtitle: Editing Queen Victoria

- Book 1 Biblio: Black Inc., $29.99 pb, 288 pp, 9781863955942

By birth a very European woman in a British court, Victoria sat at the centre of a great tapestry of royals and aristocrats, to many of whom she was related, with whom she corresponded, and whose marriages she was active in arranging. It was a game of thrones that would have tragic consequences in 1914.

Throughout her life Victoria kept extensive journals and wrote tens of thousands of letters. After her death, the journals were, at Victoria’s instruction, edited by her daughter Beatrice and the originals destroyed, in order to avoid anything liable ‘to affect the family painfully’: a delicate task given the sheer number of relatives, friends, and advisers. We will never know what was lost.

As to her letters, in 1907 a three-volume selection of them, authorised by her son Edward VII, was published. Many decades later, an Australian historian, Yvonne M. Ward, was struck by the absence of letters dealing with Victoria’s personal and domestic life. The volumes were predominantly about the monarch and not about the person. Ward, on whose PhD this book is based, decided to explore ‘who were the editors and on what principles they had operated’.

The result is fascinating, not only for the intrigue surrounding the editing, but also for the myriad issues on which the author shines a light: from public schools to prime ministers; from Irish Famine to the arcana of court life. Along the way she illuminates an era in which male dominance was the norm, to such an extent that it formed a significant dilemma for Victoria as both queen in her own sole right and as devoted wife.

At the centre of the story, Ward places Reginald Brett, Second Viscount Esher. A distinguished courtier close to the king, he was the real originator of the idea of publishing a selection of letters as a memorial. The idea was to display her character and ‘to let the Queen speak for herself’. The selection was to follow her correspondence up to the death of Albert in 1861. The king approved the proposal and put Esher in charge.

The author portrays Esher as a public and private man. The former is of a kind familiar to many: charming old Etonian, ambitious, diplomatic, secretive, a master of doing things discreetly – a man who preferred not to take a single high-profile position at court (and he was offered some plums) but rather to exercise his increasing influence by membership of powerful committees and other bodies, often working discreetly behind the scenes. His public life was focused on one thing only: retaining the king’s confidence. Machiavelli would have approved. At the same time Esher’s private life was the complex one of an active homosexual in a rigidly conformist society, particularly in a court society where good reputation was vital. Secrecy, discretion, and a sharp eye were essential.

Esher chose as editor the writer A.C. Benson. Benson’s own family upbringing had been so emotionally crushing that he was an unlikely choice to explore the life of a woman who became queen at the age of eighteen. Timid, homosexual, and a depressive, Benson described himself as ‘a good case of an essentially second-rate person who has had every opportunity to be first rate, except the power to do so’. It is clear why Esher figured he would follow orders. The only things they truly had in common were a yearning for their hedonistic days at Eton and a determination to avoid the tedium of exploring Victoria’s private life.

Although others were to be brought in, these two were the key players, with the king always the point of reference. Their riding instructions were not to give offence, not to create scandal, and to make each of the three volumes dramatic. Using the published volumes and the unpublished letters in the Royal Archives, Ward writes richly of the selection process and the subsequent editing. She shows how these two editors were much more drawn to the words of politicians and other public men than to the equally fascinating story of Victoria’s journey from isolated young woman to powerful queen. Ward tracks how they constructed a narrative about Victoria as a naïve young woman who relied on advice from older men and one who subsequently joined in a normal marriage in which the husband assumed control.

In reality, during her relatively brief marriage, Victoria bore nine children, forged a strong working relationship with her husband, and resolved the dilemma of melding her non-submissive duty as queen with her submissive duty, as she saw it, as wife. Although these developments are fundamental to understanding her character, her private thinking on them is largely missing from the published letters.

Not only did Esher and Benson severely limit the private correspondence with friends and family, they were also careful to limit the rich correspondence with her fellow monarchs, emperors, and their advisers in order not to have Victoria appear too European: the British position was what the editors sought to reflect, not that of a web of foreign families.

The political chapters in the book show how well Victoria understood the evolving nature of her constitutional role and the rights it gave her: to be consulted by her ministers; to encourage; and to warn. Ward’s descriptions of Victoria’s different attitudes to great players such as Melbourne and Palmerston show how astute she was and how severe she could be. Ward describes the increasing pressure on Esher and Benson to make the three volumes offence-proof. She writes: ‘If Esher were to incur the King’s disapproval, it would exact an enormous price – personally, socially and financially.’ And Benson knew it: ‘I must not forget that Esher ... will not hesitate to sacrifice me and throw me over at any moment. He cannot play except for his own hand.’ Edward, no intellectual, possibly never even read the work, but there were readers on his behalf, nominated, of course, by Esher.

Finally, the work was published in 1907, years after it was proposed. Only about forty per cent of the content was in Victoria’s words. Nobody was offended, but much that was important about the real Victoria was left out, unseen for decades. She remained dour.

Unsuitable for Publication is a fine piece of research and a rich source of references: a story of privilege, ambition, and fear. It is also a timely reminder that spin is not a recent invention.

Comments powered by CComment