- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Anthology

- Subheading: Writings on Asylum Seekers

- Custom Article Title: Alex O'Brien reviews 'A Country Too Far: Writings on Asylum Seekers' edited by Rosie Scott and Tom Keneally

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Australia is a country that will not be intimidated by its own decency. On 28 August 2001, as a detail of Special Air Services soldiers was dispatched to MV Tampa, Prime Minister John Howard spoke about the 438 people – mostly Afghan Hazaras – who languished aboard the freighter ...

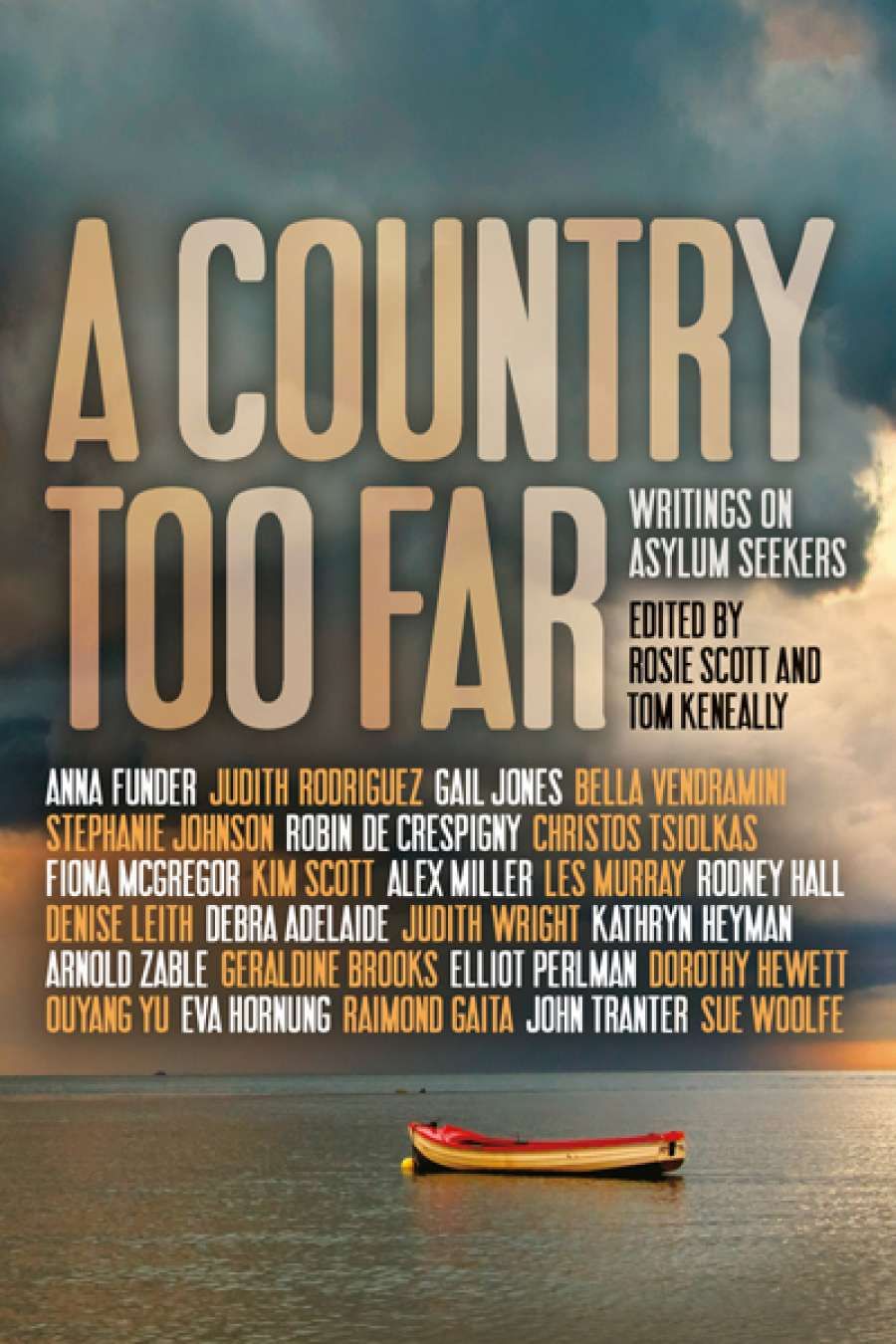

- Book 1 Title: A Country Too Far

- Book 1 Subtitle: Writings on Asylum Seekers

- Book 1 Biblio: Viking, $29.99 pb, 260 pp, 9780670077465

In A Country Too Far: Writings on Asylum Seekers, edited by Rosie Scott and Tom Keneally, twenty-seven writers of fiction, comment, and poetry write ardently about the lives of people who are brought here by war, dissidence, poverty. From the villages of Iraq and Afghanistan to boats that cross that ‘continent of water’ to our north (a place where there are no dead, as Rodney Hall writes ominously in the anthology’s opener, ‘Moonlight’), the collection evinces the trauma of exile, the disintegrating effects of detention. Tracing migration from Middle Eastern to Antipodean lands, the anthology constitutes something of a subgenre in our national letters: mostly Anglo-Australian authors on the lives of Iraqis, Afghans, Iranians (while the majority of contributions are strong, some writers’ non-native imaginations can be arid: children die, revolutions happen,little of either is hemmed to history or geography).

In her story ‘The Ocean’, Gail Jones cites David Marr and Marian Wilkinson’s indispensable account of Tampa, Dark Victory (2003) to develop what it means to witness suffering on television. ‘In the foreshortened perspective the Afghans were indistinct and collective,’ she writes, ‘a mere pattern of men.’ Across the anthology there is a strong sense of this dissociation, in which any compassion the public may have towards asylum seekers is undone by the distance and silence we have arranged between us and them.Geraldine Brooks argues, in her brief essay ‘The Singer and the Silence’, that there has been ‘an ugly brilliance’ to this silencing. ‘Whoever devised the gulag system for asylum seekers,’ she writes, ‘understood very well that the Australian heart was too big to withstand the truth.’ Many Australians ignore the distasteful conditions in which asylum seekers live and overwhelmingly support island imprisonment (at best as a deterrent to unseaworthy travel, at worst as something their origins merit). While it is evident that the Australian public uses the oblivion of distance to mitigate what is done to asylum seekers, we cannot pretend that it knows nothing of the realities – the suicides, the reprisals – to which its biases correspond.

Prefacing an extract from her novel, All That I Am (2011), Anna Funder parallels this country’s policies on ‘boats’ to the ship St Louis, which, in May 1939, returned over six hundred mostly German Jews from Cuban and American waters to continental Europe (254 of whom later died, the majority in Auschwitz and Sobibór). From the British blockade of ‘Aliyah Bet’ immigration into Palestine in 1934–48, to the detention of Haitians at Guantánamo Bay following the coup d’état in 1991, the rights of asylum seekers have often depended on the immediate demands of domestic politics rather than on agreed principles, denied in spite of the conventions we have ratified to protect them, and despite impending threats of genocide – the West captive to its paranoia and to the threat of a nebulous invasion. In his excursus on the French philosopher Simone Weil, Raimond Gaita asks the reader to question the relative importance she or he attaches to ‘inalienable’ rights (as the men of 1789 preferred), as opposed to an admittedly Christian ‘obligation to need’. ‘In humanity’s struggle against oppression,’ he summarises, ‘we have developed an ethical language [of rights] that cannot enable us to speak truthfully about or to affliction’. To précis: true degradation removes the dignity, the ‘humanness’, which underpins the modern rights movement. In the absence of dignity, the conversation on suffering then becomes merely elaborations of the moral significance of rights themselves.

And we have seen the elaborations: from an aboulic Labor Party’s proposal to launder asylum seekers through Malaysia, to Tony Abbott’s praise for the Rajapaksa brothers at CHOGM (‘I accept that by Australian standards, probably things could be done a little differently and maybe a little better,’ he conceded of the some forty thousand Tamil civilians surrounded and shot dead by the Sri Lankan Army in early 2009). Few are the permissions this country’s leadership will deny itself to stop the boats. But the truth is that the boats will never stop – they will continue, somewhere, anywhere, in their ‘archaic disarray’ (as Fiona McGregor describes in her essay ‘The Privilege of Travel’ on the origins and hypocrisies of our proxemic anxiety towards immigration) – for the wars will continue, the anti-fascists will still become émigrés, and displacements will increase as climate change becomes a daily matter of disquiet throughout the world.

A Country Too Far is a worthy collection. It develops our understanding of the inner lives of those who once hoped to discover Australia as a place to begin anew.

Comments powered by CComment