- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

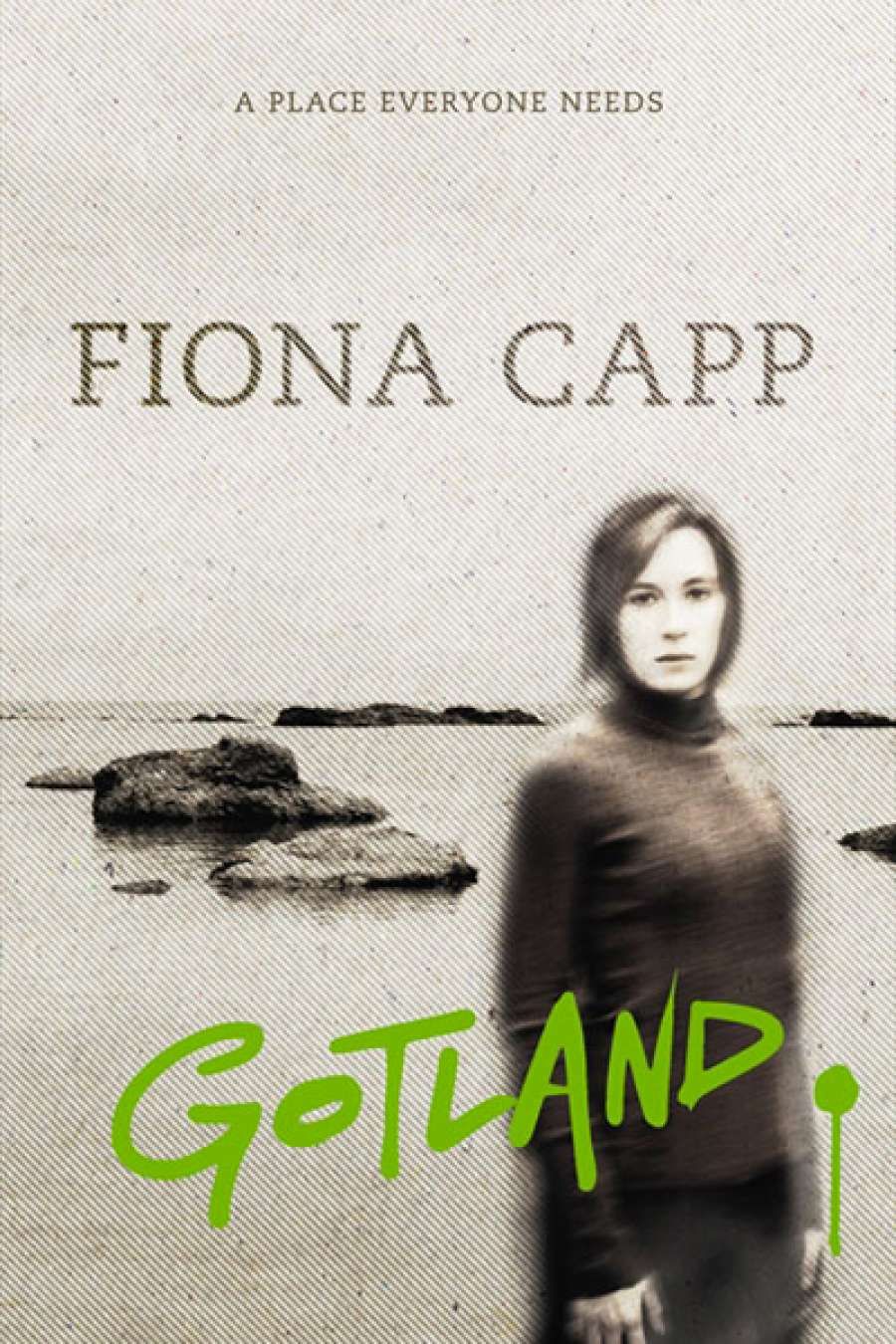

- Custom Article Title: Phil Brown reviews 'Gotland'

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Dislodged

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

While I was reading this compelling but occasionally problematic novel, I started thinking about Oscar Wilde. Pretentious? Moi? The thing is, when I’m torn between opposing views of the same thing, I tend to think of Wilde’s The Ballad of Reading Gaol … ‘two men looked out from prison bars, one saw mud, the other stars’. So I found myself in two minds about this book, mainly because, two thirds of the way through, I began to lose sympathy for the main character, Esther Chatwin, wife of a contemporary Australian prime minister (no one we know), a woman none too keen on her role.

- Book 1 Title: Gotland

- Book 1 Biblio: Fourth Estate, $24.99 pb, 295 pp, 9780732297572

Now I will admit that it is an intriguing fictional prospect, charting the interior life of a first lady, an antidote to all those articles in women’s magazines. We know the role can be burdensome. We have seen first ladies – and one ‘first bloke’ – tough it out in conditions that most of us would find intolerable, and Fiona Capp may have been thinking about them when she was writing this book. While it may be a story about a first lady, it’s one that is emblematic of any woman’s search for identity and authenticity in life. So yes, it was a lovely idea, and the eternal sea of politics is pregnant with possibilities for any writer of fiction.

In her deliciously spare prose, Capp has Chatwin looking back on the events leading to life in The Lodge and how those events shaped her relationship with her husband, David, and troubled daughter Kate, a graffiti artist, who is angry about her father’s increasing remoteness.

Esther Chatwin is a woman of integrity and her husband was a principled fellow too until his minders and spin doctors started working on him. This is where Capp risks descending into cliché. David becomes a stereotype for all those politicians who have disappointed us along the way – they are legion – and Esther ends up something of, well, a whinger. She has reservations about his rise to power after the death of his friend, who was the Opposition leader. Thoughtless of the fellow to die and pass the poisoned chalice to David.

As his political career blossoms, Esther withers. She recalls their student days when her husband was a young lefty with impossible dreams and principles to match. She yearns for the past, but we all know that is another country and that its borders are closed to us. Frankly, there’s something a little immature about Esther’s inability to accept David’s political ascent. After all, he is a politician.

She escapes all this, for a while at least, to a most unusual getaway – the obscure Swedish island of Gotland – with her sister Ros, who lives in London and has cancer. On the island, Esther meets her sister’s friend Sven, a sculptor. Artists are so much more interesting and moral than politicians, right?

Gotland is remote, Chatwin’s antipode – place of otherness – a spiritual retreat that is also a balm for her bruised soul. This temporary self-exile is a long way from both Melbourne and Canberra, where the rest of the book is set, and it must be said this is escapism of the highest order. Much as I appreciated the metaphorical aspects of the Gotland chapters and the wonderfully evocative, if bleak, descriptions of this northern landscape, I felt ultimately it showed that Esther is, I’m afraid, a bit of a flake. And why go all that way? Okay, her sister lives in London and Gotland isn’t such a stretch from there, but we have our own perfectly respectable island at the end of the world. It’s called Tasmania.

Besides these gripes, what I did like was the interiority of the novel, the sometimes meditative quality of Esther’s inward journey. Burnt-out cases are always an attraction even if they are most often men. It is refreshing to have a world-weary woman for a change. I revelled, at times, in Esther Chatwin’s dark night of the soul, her existential angst and ennui. On the other hand, I just wanted her to get over it and to give poor David a chance to enjoy being the bloody prime minister. And although this first couple are of the left, the book inspires us to ask what it would be like being a prime minister’s wife on either side of the political divide. Did Janette Howard have serious doubts about her husband’s office and suffer moral crises along the way? We know it was tough for Hazel Hawke, and Tim Mathieson had a hell of a time. And what of Dame Pattie Menzies? Did she wish that ‘Pig Iron Bob’ had pursued a different course in life?

One hopes that being a politician doesn’t necessarily mean gaining the world at the expense of one’s immortal soul. And one wonders if Tony Abbott’s wife, Margie, might turn to this novel while her other half is out on an early morning bike ride, Lycra shimmering in the early sunlight.

Comments powered by CComment