- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Japan

- Custom Article Title: Alison Broinowski reviews 'The Storyteller and his Three Daughters'

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Rakugoka

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

For centuries, Japan has magnetised the West’s imagination, evoking both fear and fascination. In the late nineteenth century, when most writers and readers in Europe, North America, and Australia had yet to see this ‘young’, newly accessible country for themselves, literary fantasies on the Madam Butterfly theme became a craze. Then, after Japan invaded its neighbours and defeated the Russian fleet, invasion fiction and drama flourished. Later, stories about geisha and yakuza served the same two purposes, attracting some and frightening others. Many readers are better informed now, yet the ‘Lost in Translation’ genre continues to cater to those who prefer Japan to remain weird and inscrutable, while ‘Last Samurai’ narrativesenable others to fantasise about the virtues of a past, more civilised age. Anime and manga continue to fascinate their fans across the world. There is a nascent revival interest in rakugo; surprisingly, the authors responsible for introducing it to Western readers are Australians.

- Book 1 Title: The Storyteller and his Three Daughters

- Book 1 Biblio: Hachette Australia, $29.99 pb, 266 pp, 9780733630293

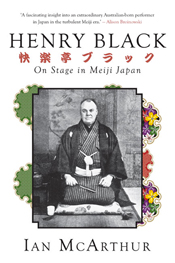

- Book 2 Title: Henry Black

- Book 2 Subtitle: On Stage in Meiji Japan

- Book 2 Biblio: Monash University Publishing, $34.95 pb, 285 pp, 9781921867507

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

Rakugoka were popular narrators, who for centuries served as entertainers and educators of the ordinary people. With no props apart from a fan, a hand-towel, and a cushion to sit on, skilled rakugoka created new worlds for their audiences, and could move them to tears or laughter. They flourished in the Meiji period (1868–1912). Later, their audiences were eroded by universal literacy and modern communications; often their stages were closed down by accidents or by the censorious authorities.

An early arrival upon this scene was Henry Black, who was born in Adelaide to Scottish parents, went to Japan at the age of seven, and became a Japanese citizen and a kabuki performer. For years Black delighted audiences with his rakugo adaptations of Western stories, delivered in fluent Japanese. He performed for the crown prince, travelled widely in Japan, and pioneered the use of shorthand to transcribe and publish his performances. He made the first records in Japan for the London Gramophone Company, technology which, along with radio and cinema, would contribute to the decline of rakugo itself. Black attracted controversy not only as a foreign interloper but as one who, like his father, a newspaper editor, advocated social modernisation. Later, as Japanese counted the costs of their rush to modernity, reaction set in, and Western ways and their advocates were no longer uncritically admired. Black was reduced to travelling with his adopted son and doing conjuring tricks. He drank copiously, got into arguments, and fell out with his family and some of his fellow rakugoka. He died in 1923, just after many of the performance stages were burned down in the great Kanto earthquake.

In 1983, a century after Black’s heyday, another Australian-born Scot, Ian McArthur, a journalist in Tokyo, came across research on Black by two Japanese scholars. He realised that Black was one of very few bilingual foreigners who witnessed the entire Meiji period, a time of turbulence and experimentation, when Japanese were avid for all they could find out about social customs, technology, government, and legal practice in the West. For the next thirty years, McArthur researched and wrote on Black in Japanese and English for thirty years, and though his enthusiasm impels his book, he doesn’t indulge in hagiography. Nor, in spite of painstaking research in Japanese, including for a PhD thesis, does he claim even now to have found out everything about Black. He searches in vain, for instance, for details of the Japanese woman Black married – Henry was homosexual and had a Japanese male partner, Motokichi – apparently in order to gain Japanese citizenship. McArthur can’t tell us, either, how or why Black and Motokichi parted. It’s not for want of trying: McArthur mines the archives, hunts for an inn where Blackmight once have stayed, and goes to Paris to investigate an obscure author favoured by Black.

Henry Black, middle, at an entertainment quarter in Tokyo, 1903 (photograph courtesy of EMI Group Archive Trust, United Kingdom)

Henry Black, middle, at an entertainment quarter in Tokyo, 1903 (photograph courtesy of EMI Group Archive Trust, United Kingdom)

McArthur was taken by surprise by Lian Hearn’s novel about rakugoka, which appeared two months after the publication of his own book on the subject. She identifies Black in an author’s note as the inspiration for Jack Green, her British rakugoka, but she mentions neither McArthur’s work, nor the foundational research on Black published by Heinz Morioka and Miyoko Sasaki in the 1980s and 1990s. Yet the two books – one fact, one fiction – could be companion volumes.

Gillian Rubinstein, after writing Tales of the Otori as Lian Hearn, turned to equally successful adult historical fiction set in Japan. The rakugoka at the centre of her story is Akabane Sei IX, from a hereditary line of storytellers, who is blessed with a good memory and a fertile imagination. But by 1884 he has failing eyesight, mounting debts, three dependent daughters, a dog which attacks foreigners like Jack Green, and a forthright, exasperated wife. Japan is in culture shock, ‘stuck between past and future’, as Sei says, and in response he has an acute case of writer’s block and relevance deprivation. Desperate for new material yet respectful of tradition, he picks up stories of Dumas and Maupassant from a Japanese friend who has lived in France, and learns about the potential of shorthand from Jack Green. He takes the risk, in a new performance, of obliquely criticising Japan’s past treatment of Koreans, and gets beaten up for it by the hired thugs of nationalists who want to stage a coup in Korea. After that, Sei chooses more cautious and more commercially successful themes.

Hearn makes Sei the narrator of his own story, setting out many of his lines and others’ responses as if in a playscript. He communes with a Buddhist monk, dead for three centuries, and personally identifies with tales of ‘glorious failures of the type [the] Japanese loved so much’. His lack of self-awareness and political naïveté are comical, and the commentary on him provided by others is subtly satirical. But he blunders on, reflecting the confusion of his life and times. Sei lives in a self-absorbed, make-believe world, loving his characters more than his family, while his daughters’ marriages collapse. Around him, his friends debate such modern ideas as the rights of citizens, the role of women, taxation, and representation, freedom of expression, Japan’s place in the world, and changing mores in the theatre, the bedroom, and the bathhouse. Delightful moments occur, as when a neighbour, jealous of Sei’s eventual success, ‘[prepares] special delicacies for us to demonstrate her displeasure’; when a Korean actor deplores the cheating of his country by exploitative Japanese who claim to be its reformers; and when the streets are suddenly overrun with bicycles.

Henry Black appealed in 1891 to his Japanese audience for cross-cultural tolerance. Human love is the same in all countries, he assured them, and in their hearts people of other nationalities have feelings no different from those of the Japanese. If Jack Green in Hearn’s novel had said that, Sei might have been surprised at such a notion, but would probably have agreed.

Comments powered by CComment