- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Australian History

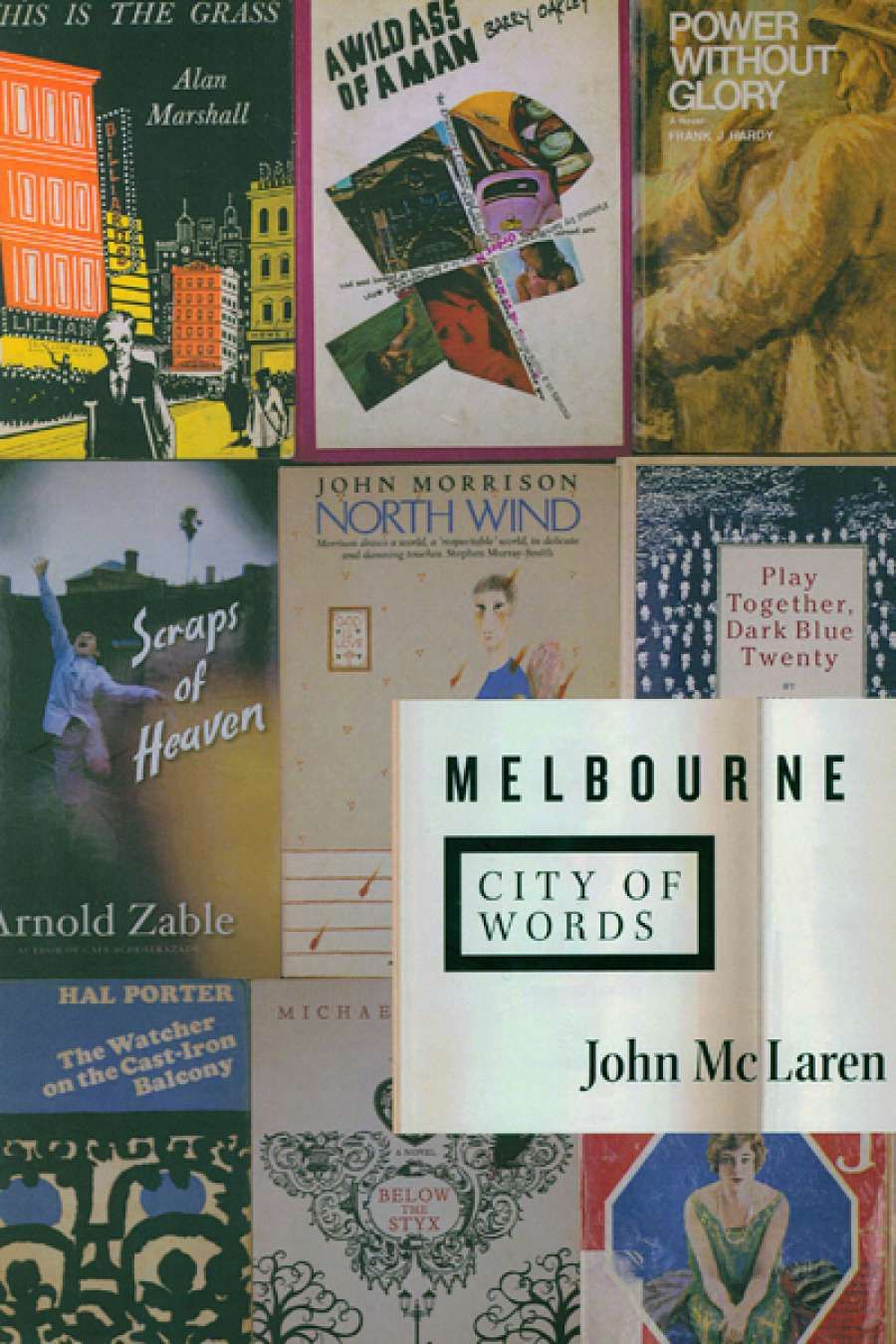

- Custom Article Title: Simon Caterson on 'Melbourne: City of Words'

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: This backyard thy centre is

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

To judge by John McLaren’s thought-provoking survey of 200 years of writing about Melbourne, the city’s most insidious negative feature for many observers – wrong-headed though they may be – is dullness. In George Johnston’s My Brother Jack (1964), the narrator David Meredith rails against the suburbs as ‘worse than slums. They betrayed nothing of anger or revolt or resentment; they lacked the grim adventure of true poverty; they had no suffering, because they had mortgaged this right to secure a sad acceptance of suburban respectability that ranked them a step or two higher than the true, dangerous slums of Fitzroy or Collingwood.’ In affluent suburbs like Malvern, Graham McInnes in The Road to Gundagai, a memoir first published in 1965, saw ‘immense deserts of brick and terracotta, or wood and galvanised iron [that] induce a sense of overpowering dullness, a stupefying sameness, a worthy, plodding, pedestrian middle-class, low church conformity’.

- Book 1 Title: Melbourne

- Book 1 Subtitle: City of Words

- Book 1 Biblio: Arcadia Publishing, $39.95 pb, 264 pp, 9781925003079

Each of these extracts suggests that the flatness of the city – the nice suburbs are seen as only a step or two higher in ranking than the slums, and the image of deserts similarly suggests a levelness in the terrain – means that Melbourne is a city that spreads itself thin. As McLaren notes, Australia’s second major city was planned to be more rational in layout than haphazard Sydney, which to this day promotes itself as a city of villages, albeit villages that in actual fact are all jammed up together. Where Sydney has density, Melbourne has capaciousness, with greater physical distance between both houses and people.

In Melbourne, the traditional quarter-acre block means that households established there tend to be self-contained; hence a backyard often is a whole world. Occasionally a writer such as Christos Tsiolkas in his novel The Slap (2008) will, in a moment of literary inspiration, recognise this essential truth about Melbourne. Perhaps the best way to understand the city is not to try to sum it up across streetscapes, ethnicity, and class, but instead to focus on the intensity and particularity of life in individual dwellings.

The central act of domestic violence and all the consequences that flow from it, as depicted in The Slap, are just so suburban Melbourne – an incident such as a man slapping a child not his own during an otherwise forgettable backyard barbeque conceivably might not carry the same dramatic weight if it took place in São Paulo or New Orleans or Beijing, which isn’t to say that it shouldn’t.

Melbourne: City of Words – organised, for the most part, chronologically – begins with the first European settlement at Port Phillip and ends with Michael Meehan’s meditation on the ghost of Marcus Clarke in his novel Below The Styx (2010) and with Tony Birch’s contemporary evocation of the spirits of Melbourne’s original Indigenous inhabitants in the poem ‘The True History of Beruk’. There are chapters on schools and sport. Schooldays receive detailed attention, for, as McLaren explains: ‘In no other Australian city, and possibly nowhere in the world outside Westminster and the Quay d’Orsay, is the school you went to considered as important as it is here.’

McLaren, an emeritus professor in the College of Arts at Victoria University, has a relaxed style of exposition and comes across more as a book-lover than an academic critic with a career-advancing theoretical point to make. Though McLaren clearly is interested in the operation of class, the Marxism is worn lightly, and the survey as a whole is eclectic and inclusive. Indeed, an exaggerated class consciousness and overdeveloped sense of history could easily distort the picture of Melbourne, since the whole point about a sprawling modern Australian suburban city is that it operates to defuse social tensions and be a place where the past, like the neighbours, may be ignored.

By the time you have travelled physically from the poorest part of town to the richest, your disquiet at social inequality in Melbourne may have evaporated due to the sheer length of the journey. So many waves of immigrants, from the Irish diaspora fleeing the Great Famine to Jewish refugees from the Holocaust or more recent asylum seekers who have arrived by boat, are trying to escape history rather than transplant it to a place like Melbourne.

In any case, Melbourne was planned so that there would be no central location for mass demonstration, no epicentre of popular unrest. The inner-city slums of previous generations are now among the most desirable parts of town in which to live, while the people living in the public housing high-rise apartment blocks in those same areas may enjoy some of the best views the city has to offer.

In contrast to the negativity quoted above from Johnston and McInnes, Helen Garner expresses a view of Melbourne more au courant with the city’s temperate expanse. Fittingly, McLaren quotes this passage from the novel Monkey Grip (1977) seen through the eyes of the hopeful young female protagonist: ‘Summer-night bicycle rides, rolling home to the big house with a big heart, sailing through floods of warm air, the tyres whirring on the bitumen, then over the gutter and onto the park, and feeling the temperature drop under the big green leafy balloons.’

Comments powered by CComment