- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

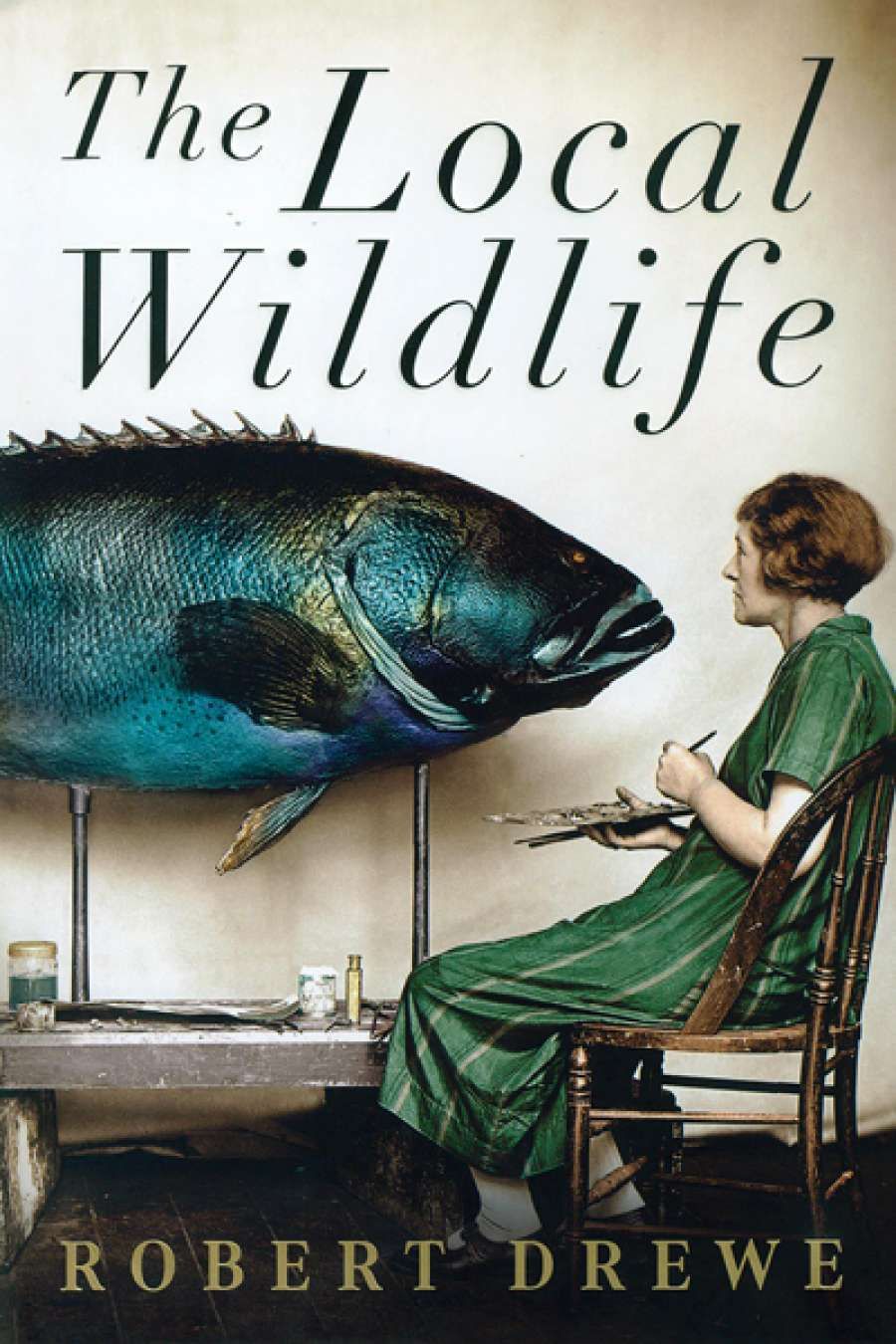

- Custom Article Title: Dennis Haskell reviews 'The Local Wildlife'

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Mayhem

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Pre-teen and early teen years had me and many others enjoying Ross Campbell’s witty column in the Sunday Telegraph newspaper about the goings-on in ‘Oxalis Cottage’, a fictionalised version of his Sydney home. Robert Drewe’s often hilarious columns for The Age and The Weekend West are a kind of modern equivalent, and a selection of them is brought together to form The Local Wildlife.

- Book 1 Title: The Local Wildlife

- Book 1 Biblio: Hamish Hamilton, $29.99 hb, 245 pp, 9781926448482

Drewe’s patch is sometimes his own homes – a former tantric brothel and a house with a beauty parlour in the garage and a python in residence. Ross Campbell could never have imagined such things, but they seem almost dull beside the other wildlife Drewe encounters in the Northern Rivers, the hippy country in and around Byron Bay, where humans are sometimes close to nature and sometimes very much part of it. Here the ‘rainforest casts such a strange, otherworldly aura over its inhabitants’ that it is ‘the place with the highest unemployment in Australia ... the most dangerous stretch of highway, the most floods, the most tooth decay, the most public-bar fights, tobacco smokers, cannabis users, home births, resistance to vaccinations, and – on anecdotal evidence – sea-change adulterers’. It also has, on Drewe’s evidence, brown snakes, red-bellied black snakes, cane toads, cormorants choking on eels, duck-monstering swamp hens, crows that attack windscreen wipers, Brahman-cross bulls, rats, meat ants, dingo-hybrid feral dogs, paralysis ticks, echidnas, tiger quolls, sharks, worms that cover the dining room ceiling, and Darwin knows what else. Drewe’s presentation of the animal world tends to be one of nature red in tooth and claw, ameliorated by his accepting ‘the law of the jungle and so on’.

The people are coterminous with the animals, less vicious but sometimes feral in a civilised way or quite zany. In one episode, Drewe finds himself ‘at a party thrown by rich hippies where I knew no one, so I introduced myself to a group of people around my age. They were named Prometheus, Willow Wand, Aquamarina and Colin.’ Drewe comments, ‘I was feeling pretty stodgy in the name department, although Colin was some consolation ... his yellow turban and satin pantaloons notwithstanding.’ Elsewhere we encounter the ‘unlikely’ pairing of Drewe’s friend Trevor, ‘the conservative macadamia-nut farmer and coffee grower’, and ‘his new partner, Destiny’. Destiny teaches ‘Life Alignment’ and is ‘one of this region’s foremost authorities on golden-mean ratio, implosion, gravity creation and the nature of the fractal field in sacred geometry architecture, art, biology, biofeedback and myth’. Drewe tells us that much of what she tells him ‘went over my ignorant pragmatic head’. He is a master of deadpan understatement and of bathos. Trevor is building owl-houses to encourage owls which will eat the rats that eat his nuts but Destiny wants him to ‘Rediscover Being and enjoy the stillness of eternity.’ Trevor grunts: ‘Sounds like being dead to me ... Plenty of time for that later on.’

Drewe is a kind of Trevor but more bemused, a pragmatist in a world that makes Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha County seem like a bastion of Enlightenment rationality. The Northern Rivers, Drewe comments intimately, ‘let’s be frank, is not idiot-free’. Somehow you feel he knows a bit about understatement and irony. Reading the local paper, Drewe observes, ‘Whimsical unconventionality is encouraged here.’ Drewe’s articles are full of it, and the key to their success lies in his stance and tone. Life in this vivid environment can be ‘like being in a cartoon’, and Drewe knows when to let the frenzied animals and mad characters speak for themselves. He has a light touch and never overtly moralises or otherwise asserts his superiority to any of his subjects. It’s easy to miss the fact that these light-hearted articles reference Schopenhauer, Stendhal, and Pliny the Elder, and involve a vocabulary that includes ‘cartilaginous’, ‘aracologists’, ‘cryptozoology’, and ‘diprotodontids’. Drewe is accepting of nature’s cruelties and indulgent towards human fallibility. There is a long tradition in Australian writing of seeing the Bush as superior to the city, but Drewe is no Banjo Paterson. Of course, he is not in the outback but in a kind of rural suburbia. There is also a long line of male writers finding the average nerves of ordinary Australians to be contemptible, Hal Porter, A.D. Hope, and Patrick White among them. Not far beneath the comedy of Edna Everage and Sandy Stone is a slur of contempt. Robert Drewe is not like this either; he seems to enjoy human eccentricity.

Because of their sources in newspapers, the pieces in The Local Wildlife are of uniform length, which seems regimented when they appear in book form, and there is some repetition. Nevertheless, for brilliant description, lively simile (a red-headed boy has ‘pale, lightly freckled skin, like fly-spots on a windowsill’) and a gift for drama and narrative, Drewe is hard to match, and these small, apparently easy pieces have much in common with his more ambitious literary work. Drewe acknowledges that some of them have found their way into Grace (2005) and The Rip (2008). An enterprising ABC producer could easily turn them into sharp dramatic vignettes à la Clarke and Dawe. Australia also has a strong tradition of the tall tale, but the book’s cover flap claims ‘these short, short stories are true’. How true? ‘Aracologists’, we are told, ‘are great kidders.’ So too is Drewe; on the other hand, ‘human mayhem – there’s a lot of it about’.

Comments powered by CComment