- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Picture Books

- Custom Article Title: Picturing War

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Stephanie Owen Reeder reviews 'ANZAC Biscuits' by Phil Cummings and Owen Swan, 'An ANZAC Tale' by Greg Holfeld and Ruth Starke, 'The Promise' by Derek Guille, Kaff-eine, and Anne-Sophie Biguet, 'Vietnam Diary' by Mark Wilson

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Depicting war in a picture book requires a deft hand. Historical imperatives need to be considered, while also avoiding glorifying war for a young and impressionable audience. Ideally, such books should promote informed discussion rather than mindless militarism.

ANZAC Biscuits (Scholastic, $24.99 hb, 32 pp, 9781742833460), by Phil Cummings and Owen Swan, is a sensitive portrayal of both sides of a war story. While Rachel and her mother are baking biscuits at home, Rachel’s father is fighting in Europe during World War I. In alternating double-page spreads, sounds, smells, and sensations link the lives of Rachel and her father, as domestic elements such as a crackling fire, clanging pots, and sticky treacle are echoed by the smoke of bombs, gunfire, and cloying mud. The final image, which shows the father eating the biscuits that have been so lovingly made for him, provides solace.

Cummings’s text cleverly highlights the different living conditions on the home and battle fronts. However, the overall drabness of the colour palette in Swan’s kitchen scenes, plus the lack of visual drama in his battle scenes, detracts from the story. A stronger visual narrative would have added poignancy to this interesting study of the interconnected but very different lives of family members during war.

David Cox’s The Fair Dinkum War(Allen and Unwin, $24.99 hb, 32 pp, 9781743310625) deals with daily life at home in Australia during World War II. Told from a child’s perspective, and based on Cox’s own experiences, the text is an entertaining series of reminiscences about a young boy living in the early 1940s. Cox covers everything from the Japanese bombing of Darwin to rationing and coupons, zigzag air-raid trenches in school playgrounds, blackout curtains, and the importance of ‘helping the war effort’. This is a nostalgic child’s-eye view of what it is like to live in a country at war. Cox’s trademark loose-lined illustrations are full of movement and often humorous details which, like his text, showcase the time, the place, and the people.

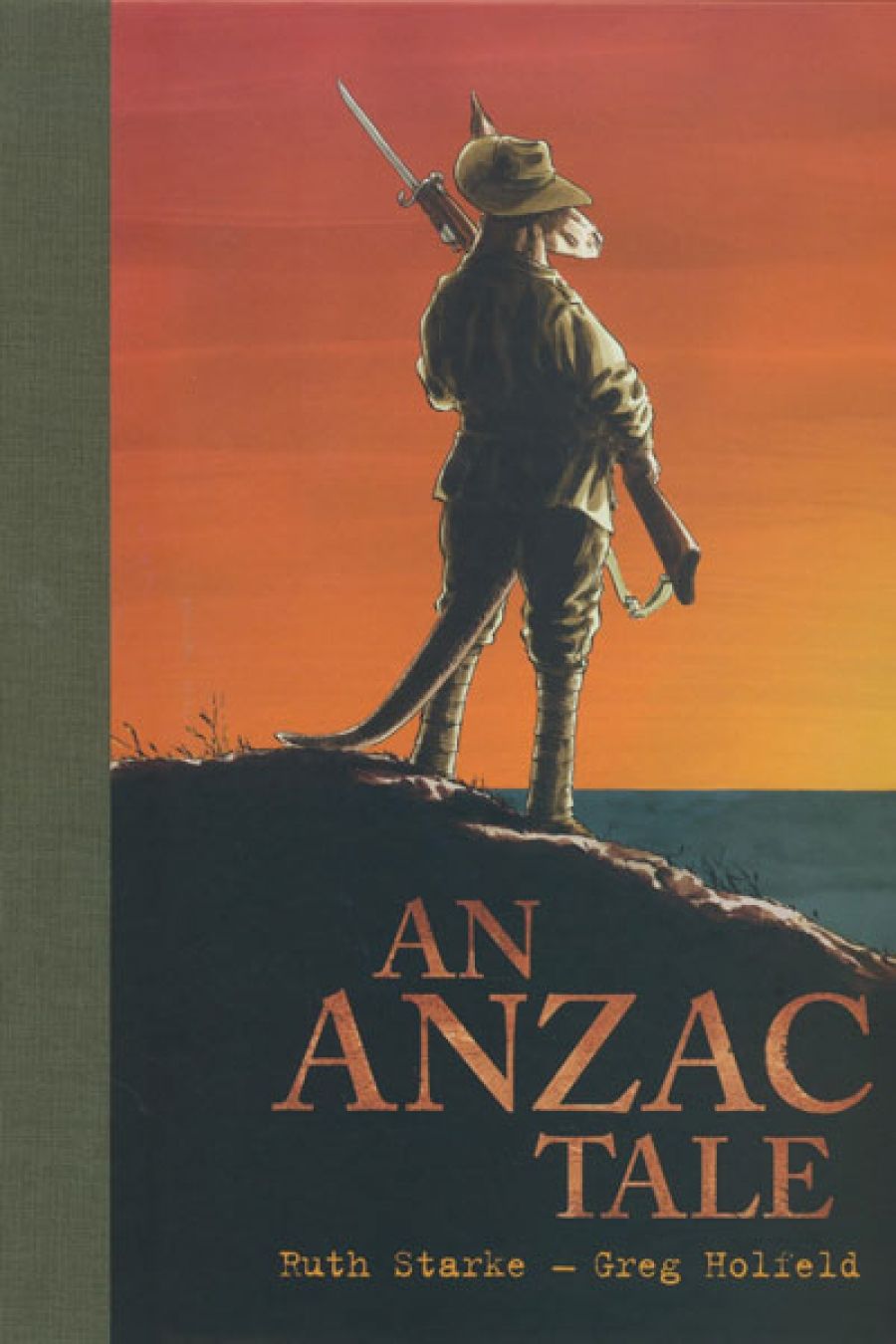

Aimed at an older audience, An Anzac Tale (Working Title Press, $29.95 hb, 72 pp, 9781921504532) explores the realities of trench warfare during the epic defeat that was the Gallipoli campaign. Using a graphic-novel format, Greg Holfeld presents Ruth Starke’s minimalist but telling text almost exclusively in speech balloons.

The story follows the lives of the two main characters, Wally and Roy. Boyhood friends from a small farming community, they enlist together in what they regard as a great adventure. Starke’s impressive research is reflected not only in the depth of material contained in the text, but also in the notes and timeline presented at the end of the book. Unfortunately, there is no list of background reading.

Attention to detail is also evident in the illustrations. Holfeld creates his characters by anthropomorphising Australian animals and birds. The majority of his Australian soldiers are muscular kangaroos in slouch hats, while birds such as cockatoos represent officers. Holfeld’s panels bristle with movement and dynamic imagery, especially in the battle scenes.

An Anzac Tale is an impressive book; without sentimentality, it relates the everyday realities of the Anzac story through a seamless interplay of words and images. There is the obligatory heroism and mateship, but there are also fleas, trench foot, rotting cadavers, enervating heat, flies, and diarrhoea. In this way, Starke and Holfeld portray the Gallipoli campaign in an uncompromising way for a new generation. This is a thought-provoking, highly accessible, and graphically striking interpretation of the Anzac legend.

The Promise: The Town that Never Forgets (One Day Hill, $24.99 hb, 40 pp, 9780987313966) deals with the aftermath of war. In 1918, Australian soldiers fought and defeated the Germans in the small French town of Villers-Bretonneux. The people of the village vowed never to forget the Australian soldiers. After the war, a plaque was erected to recognise their contribution, and Victorian school children reciprocated by raising money for the rebuilding of the village school. Today, the children of Victoria School in France continue to learn about Australia.

Author Derek Guille also relates the connected stories of a recent visit by members of the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra to Villers-Bretonneux, and that of World War II soldier and musician Nelson Ferguson. A translation into French of Guille’s text by Anne-Sophie Biguet is also included. The result is a book that is filled with multiple stories and interesting information, but that is rather cluttered with text. The idiosyncratic and interpretative illustrations by Kaff-eine are colourful and unusual, but they add little to the narrative. This is a well-meaning book that tells an important story about people from two countries honouring both the past and each other. Unfortunately, it tries too hard to do too much within the artistic and narrative confines of the picture book format.

The strength of Mark Wilson’s Vietnam Diary (Lothian, $24.99 hb, 32 pp, 9780734412744) lies in his visual representation of people and places. Wilson examines how war can divide families, not just physically but emotionally and philosophically. Brothers Leigh and Jackson grow up in suburban Melbourne in the 1950s. They both have plans to play cricket for Australia one day; a highlight of their childhood is going to their first cricket Test match with their father, a World War II veteran. For younger brother Jason, his MCG ticket becomes talismanic.

The brothers are close friends, but the Vietnam War soon separates them. While Leigh joins the anti-war movement, his brother thinks that, in the Anzac tradition, Australia should be involved. When Jason is conscripted, he volunteers to go to Vietnam, despite his brother’s condemnation of his actions. An emotive double-page spread towards the end of Vietnam Diary features a copy of Leigh’s conciliatory letter, which his brother has not had a chance to read, and the image of young Jason looking directly at the reader as he heads off into the battle of Long Tan and the terrible fate that awaits him.

Wilson leaves it for the reader to find out more about the Vietnam War, the reasons for Australia’s involvement in it, and for the strong anti-war movement in Australia at the time. Wilson’s illustrations are compelling, featuring textural photorealistic sketches, and paintings of people and places, combined with newspaper extracts, ephemera, and letters, all of which add a personal touch. Vietnam Diary is a well-designed, thoughtfully rendered, and moving story about how family members can be torn apart by war, even when they are ostensibly on the same side.

Picture books such as these ones provide an important stepping-stone for generating children’s interest in and meaningful conversations about not only the historical context of war but also the enduring consequences that war can have on both nations and individuals.

Comments powered by CComment