- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Custom Article Title: Alison Broinowski reviews 'Lightning' by Felicity Volk

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The dead heart

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Few first novelists are as assured and articulate as Felicity Volk. She has designed an elemental structure for her story: wind, fire, earth, and water each have a section. Her time frame goes centuries deep, naming ancestors who, in the style of Genesis, begat and begat seven generations, until they reach Persia, an Australian with Arab, European, and British heritage. A thirty-something pathologist, Persia is a modern product of multiculturalism and globalisation, as is the Australian society she encounters on her drive from Canberra to Alice Springs. Her forebears were participants in similar processes.

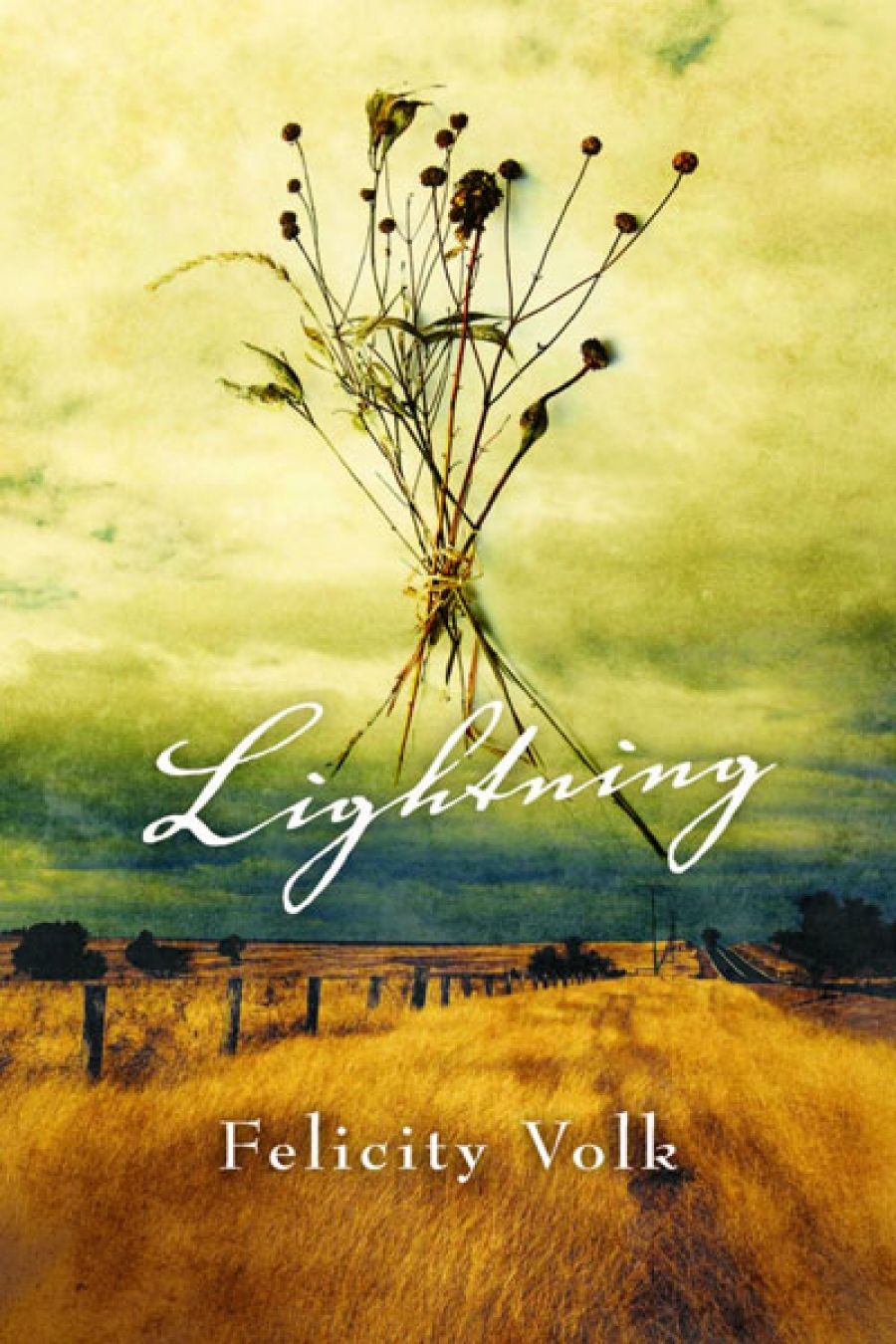

- Book 1 Title: Lightning

- Book 1 Biblio: Picador, $29.99 pb, 380 pp, 9781742612157

Few first novelists, though many have tried, issue such an immediate challenge. Volk’s first section is a concentrated essay on the world’s winds – the sirocco, diablo, gregale, and so on. This leads her to how Persia’s forebears, afflicted by winds in various places, met and procreated. She progresses to January 2003 and the Canberra bushfires, when the pregnant Persia can’t reach her midwife in time, and has her baby alone. With her dead daughter, she sets off past ‘Paddock George’, which used to be Lake George, in the direction of the baby’s father. But events conspire to divert her to the west, on the road to the dead heart.

None of which is surprising, considering that Volk’s parents, both teachers and writers, took her travelling in Europe for a year as a child. She then earned a degree in English, took off again to travel in Asia, became an Australian diplomat, and worked in Bangladesh and Laos. She scatters literary allusions and remarks in various languages through her text. Silence, she says (reminding you of one of those smart definitions of postmodernism) is ‘less the space between sounds than an act of making room for the often neglected’. Volk is aware, as she tracks Persia through ‘dry and unforgiving places’, of other Australian literature of the desert, camels included. Persia, whose grief renders her speechless for several days, is nicknamed ‘Alice in wonderland’ by a truckie, and the name sticks. She encounters characters as witty and weird as anything in Lewis Carroll; they have extraordinary stories to tell. As Persia considers suicide, narratives as fantastic as those in the Arabian Nights intervene to keep her from it. Some of the stories that fend off sleep, despair, or death are told by strangers; some are her own, others are Ahmed’s.

Grief-stricken though she is, when Persia drives out of smoky Canberra in her unroadworthy car, with one bag for herself and a suitcase containing her dead baby, it is rather a stretch to accept this as the behaviour you would expect of a hospital pathologist. Ahmed, whom she encounters in Grafton, is a doctor, a refugee from Pakistan or Afghanistan, depending on who’s asking, and he is lucky to have secured a hospital orderly’s job in Australia. He can recite Proust and Lewis Carroll, treat Persia’s lesions, and help her to embalm the baby. But when he invites her to drive away into the desert in his clapped-out Falcon, you strain to believe that either of them would take such an irrational plunge down the proverbial rabbit hole. The magic realism, herbal remedies, mummification spices, and bizarre coincidences that follow may demand rather more suspension of disbelief than many readers are able to summon.

Yet three more of Volk’s talents keep you reading, just as Scheherazade kept the Shah engrossed for a thousand and one nights. One is her subtle wit, another is her encyclopedic – or maybe Wikipedic – knowledge of facts and languages, and a third is her storytelling itself. Persia and Ahmed beguile the hours of silence in the Falcon with verbal jousts, puns versus erudition, and shaggy-dog stories. Grafton: graft-on, grief-town. There are extended anecdotes about scientific successes and human failures in medicine on several continents; and simultaneous wordplay and mind games, as when Persia asks him to check her perineal sutures, which he inserted at the Grafton hospital, and Ahmed represses unprofessional urges by silently reciting the relevant parts of the female anatomy in Latin. ‘Put it in a foreign tongue and you won’t be tempted to put a foreign tongue in it,’ he reflects. ‘The problems only start when it’s translated into the language of the everyman. Then its mysteries become accessible.’

There are plenty of foreign tongues around: at the mineral hot spring in Lightning Ridge, Persia hears Polish, Hungarian, Portuguese, Italian, and possibly Cuban Spanish. ‘It was Babel,’ she recalls, ‘only it wasn’t a tower reaching to the heavens, it was a pool … that led to … the hot hell that boiled its waters. And there was no God masterminding any of it.’ But at a cemetery in Bourke, God’s attention is fragmented, with Christian denominations and ‘Independent’ on one side, Chinese and Muslim graves on the other. Persia apologises for some Australian graffiti. ‘Who’s Australian?’ Ahmed asks.

To answer him, Volk offers multicultural voices and many stories: Ricardo, the Italian who died laughing; his wife Carla, who died of hyper-dehyration from weeping for him; their twin sons who shared a German woman; Faisal and Fatima, Persia’s Afghan ancestors; Frederick, her Lutheran great-grandfather; and so on, ‘their common nightmares, their shared dreams’. At the end of their road, Persia and Ahmed say, grinning, ‘Welcome to Australia’.

Comments powered by CComment