- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Children's Fiction

- Custom Article Title: Benjamin Chandler on 'A Very Unusual Pursuit: City of Orphans'

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Bogling

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The Victorian era has gripped the collective imagination of speculative fiction writers in much the same way the medieval period influenced our forebears. The nineteenth century gave us the Penny Dreadful, Dracula, and Frankenstein, and the melding in fiction of fantasy and reality, superstition and science. A spike in child labour was followed by its marked decline as society began associating childhood with innocence.

- Book 1 Title: A Very Unusual Pursuit

- Book 1 Subtitle: City of Orphans, Book One

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $14.99 pb, 324 pp, 9781743313060

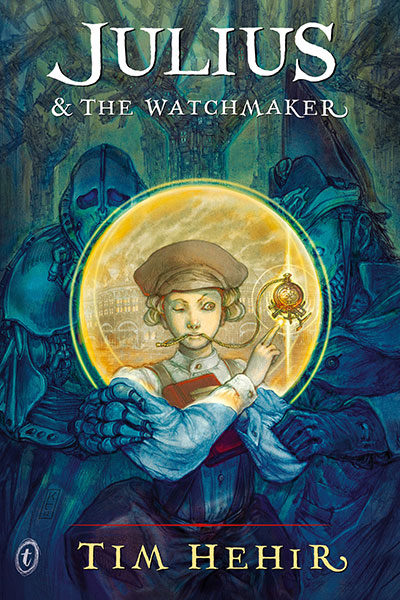

- Book 2 Title: Julius and the Watchmaker

- Book 2 Biblio: Text Publishing, $19.95 pb, 384 pp, 9781922079732

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 2 Cover Path (no longer required): images/stories/issues/352_June_2013/9781922079732.jpg

In fiction, the travails of childhood in the 1800s can be rewritten through contemporary conceits. Labour brings agency and freedom. Child protagonists, orphans for the most part, can come into their own. This is often what Young Adult novels are about. The protagonists in Catherine Jinks’s A Very Unusual Pursuit and Tim Hehir’s Julius and the Watchmaker both work, and it is through work that they are called to adventure.

Birdie McAdams is a bogler’s apprentice. Her youth and angelic voice make her the perfect bait for bogles, which in Jinks’s nineteenth-century London eat mostly children. Birdie lures the bogles into the traps set by her master, Alfred Bunce, who then does them in. It is simple and effective, but also dangerous. Enter Edith Eames, a noblewoman with an interest in folklore. Appalled that Mr Bunce is using children to catch bogles, she proposes a scientific approach to bogling more in line with her contemporary ideals of both childhood innocence and the scientific method. When this poorly matched trio discovers a man trying to summon and tame bogles using street urchins as bait, they form a daring plan to put an end to it.

There is an attention to detail in Jinks’s work that helps ground the more fantastic elements, while the locations – haunted mansions, graveyards, spooky wells, a chilling insane asylum – lend the work its Gothic atmosphere. The action moves smoothly from bogle hunt to fiendish plotting and back again, though too often it is the adult characters who step in to set things right. Much of the tension is drawn from Miss Eames’s desire to pull Birdie out of work and from Birdie’s own desire to fulfil her promise as a bogler’s apprentice. The fact that, as a girl, Birdie cannot actually graduate from apprentice to full-time bogler rather downplays the likelihood of her setting her own course in the future.

Tim Hehir’s young protagonist, Julius, delivers books for his grandfather. This turns out to be more dangerous than one might imagine given the apparently lethal army of urchins haunting the streets of Hehir’s version of nineteenth-century London, searching for unwary prey. When two peculiar gentlemen come to the bookshop looking for the same mysterious diary, Julius upheaves his comfortable life and lurches from crisis to crisis, sometimes through time itself, in his attempts to first avoid trouble, then to stop it, and finally to erase it altogether.

The time-travelling is problematic; it is used sparingly, and then as the hand of god to solve the really serious problems so that Julius doesn’t have to do so himself. As a result, the plot is startlingly straightforward for a time-travelling narrative. Hehir’s young protagonist makes plenty of mistakes, showing a truly monumental lack of good sense, but rewriting those mistakes with a quick time jump means that Julius never has to learn anything from his adventures, which in turn robs the resolutions in the book of any energy.

Time-travelling is hard to pull off convincingly, and the author’s explanation of its workings is needlessly convoluted. Of much more interest here is the parallel mechanic of extra-dimensional travel, from which the true narrative impetus springs. The villain of the piece, Jack Springheel, attempts to recreate time travel, but inadvertently invents a machine capable of punching holes into alternate realities, from which he plans to steal a great many riches. The only problem is that the first alternate dimension he intends to rob is populated by insatiable red-eyed monsters. It is up to Julius and his time-travelling allies to thwart Springheel before London is overridden by horrific invaders and a growing army of clockwork zombies. When the action commences, Hehir’s pacing is perfect.

Both authors shy away from issues of gender. As mentioned, Birdie can never become a bogler in her own right, though the ending suggests this may change in later books in the series. While Miss Eames shows a scientific bent, her attempts to bring the scientific method to bogling are rendered silly and naïve (though again this might be something Jinks intends to explore in later books). Similarly, the only two female characters in Hehir’s work are given short shrift. One flits on and off the page and is relegated to a bit of fussing and the preparation of tea and crumpets. The other – the leader of a band of child thieves – does little more than become a hostage.

There is a sense in which the young protagonists, if left to their own devices, might become agents in their own right, overcoming whatever obstacles may bar their way. Unfortunately, neither Julius nor Birdie is given much of a chance. In the moments when Birdie and Julius must act, they do, and the books shine, but too often Jinks and Hehir seem reluctant to trust their protagonists.

Comments powered by CComment