- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Religion

- Custom Article Title: Ray Cassin reviews 'Soldier of Christ: The Life of Pope Pius XII' by Robert A. Ventresca

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Pius and the Nazis

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Not the least portent of change in the Catholic Church since the Argentine Jesuit Jorge Bergoglio was elected as Pope Francis earlier this year has been mounting speculation that the new pontiff will disclose all documents in the Vatican archives concerning the most controversial of his twentieth-century predecessors, Eugenio Pacelli, who reigned as Pius XII from 1939 to 1958.

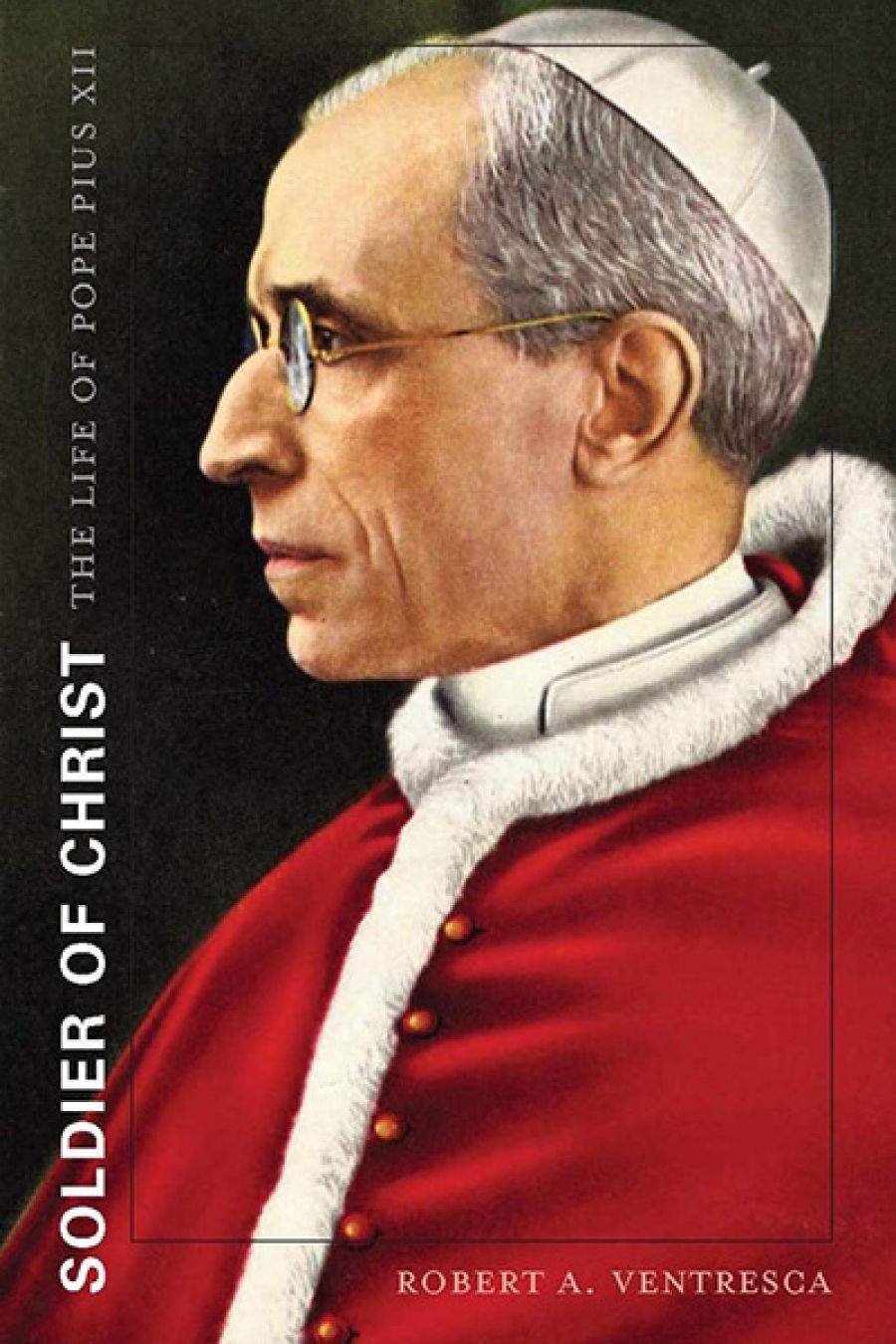

- Book 1 Title: Soldier of Christ

- Book 1 Subtitle: The Life of Pope Pius XII

- Book 1 Biblio: Harvard University Press (Inbooks), $35 hb, 405 pp, 9780674049611

At least since the publication of Rolf Hochhuth’s play The Deputy in 1963, Pius has been widely reviled for his public silence during World War II on the subject of the Holocaust. Others have sought to defend him, citing the many thousands of Jews who were given refuge in Catholic institutions throughout Nazi-occupied Europe, and countless more who were aided or concealed by individual Catholics. This happened with Pius’s active, though surreptitious, encouragement, as was acknowledged at the time by prominent Jewish leaders such as Chaim Weizmann, who later became the first president of Israel: ‘the Holy See is lending its powerful help wherever it can to mitigate the fate of my persecuted co-religionists.’ Similar wartime endorsements were made by the chief rabbi of Rome, Israel Zolli, and the chief rabbi of Palestine, Isaac Herzog.

To act in mitigation of a great evil is not the same, however, as forthright public condemnation of the evil. The defences offered of Pius’s wartime conduct have never persuaded his critics. On the contrary, they have usually sharpened the attack, for if the pope and officials of the Roman Curia knew of the plight of Europe’s Jews and were willing to rescue as many of them as they could, why did they stubbornly adhere to a policy of ‘reserve’ in their public comments?

Pius XII, more than most popes, was a polarising figure, and previous studies of his pontificate have, accordingly, tended to be either fiercely polemical, if from his critics, or bordering on the hagiographical, if from his defenders. This latest biography, by Robert Ventresca, associate professor of history at King’s University College, University of Western Ontario, strives to avoid these extremes. Ventresca builds his case from an impressive marshalling of the available evidence. It is cogently argued, and lucidly, if soberly, written. Pacelli’s human qualities are apparent, and the cold monster portrayed in Hochhuth’s play is dismissed as the vicious caricature it is. The Pius depicted here is not a corrupt man.

He is, nonetheless, a man who cannot be acquitted of massive and catastrophic misjudgement in his response to the depredations of the Nazis, above all with regard to their attempted annihilation of the Jews. Whatever Ventresca’s intent may have been in writing this scholarly and mostly dispassionate biography, the result is a consolidation of the case against Pius. Opening the Vatican archives may yet reveal much about the aims of papal diplomacy during World War II, but enough is already known to conclude that by refusing publicly to condemn the persecution of the Jews Pius achieved nothing except an undermining of the moral authority of the church, and of the papacy in particular.

Pius sought to justify ‘reserve’ by arguing that to speak openly would provoke the Nazis to even greater savagery and to reprisals against the church that would prevent it doing even the little it could do to help their victims. In his own mind, Pius was exercising prudent restraint in order to forestall a greater evil. As Ventresca asks, however:

Were such prudence and caution appropriate for the Vicar of Christ? Was it the behavior of a prophet, a martyr or saint? [This is not just a rhetorical question, since Pius’s defenders continue to push for his canonisation.] With millions of innocent civilians already dead, and thousands more facing a similar fate, what greater evil could there be?

A biography of Pius that focused on his wartime diplomacy, or on the Vatican’s abandonment and effective betrayal of the Catholic Centre Party, which by 1933 was the chief remaining constitutional opposition to the Nazis in Germany, would inevitably bear the hostile tone of John Cornwell’s Hitler’s Pope: The Secret History of Pius XII. When that book was published in 1999, Cornwell said that he had begun his research by seeking opportunities to vindicate Pius but had ended up thinking that the pontiff was far worse than he could have imagined him to be.

If Ventresca avoids Cornwell’s rancour, it is not because he tries to excuse Pius’s errors, which are laid out for all to see, but because Soldier of Christ tries to take a longer view of the significance of his pontificate. Pacelli was not only the man who as secretary of state to Pius XI negotiated the concordat (treaty) between the new Nazi government of Germany and the Holy See in 1933, and who, after becoming pope himself, clung to a diplomatic stance of strict neutrality long after it had become morally untenable. He was also the pope who, it can be argued, initiated the Catholic Church’s engagement, tepid and faltering though it has been, with the modern world.

The strongest evidence for this claim lies in his internationalisation of the church’s clerical leadership. In Asia and Africa, local hierarchies emerged, displacing European missionaries. Pius ended the Italian majority in the College of Cardinals (though Italians would remain by far the largest bloc for long after his death in 1958), and appointed the first Indian and Chinese cardinals. During his long pontificate, Catholicism began to acquire in fact the genuinely universal character that it has always purported to possess in doctrine.

That process did not accelerate, however, until the Second Vatican Council (1962–65), which was summoned by his successor, John XXIII, a man who in nearly every respect – background, personal demeanour, and pastoral style – was the antithesis of Pius. Some argue that Pius XII’s doctrinal writings contributed to the spirit of aggiornamento (‘today-ness’, i.e. updating) that animated the council’s deliberations, but this judgement depends on a very selective reading of his encyclicals. Divino Afflante Spiritu (1943) did indeed unshackle Catholic biblical scholars, dispelling suspicions of the use of historico-critical methods in the study of the scriptures. Mediator Dei (1947) encouraged a more participatory approach to the liturgy, which became the greatest single change wrought at Vatican II. But against these must be setHumani Generis (1950), which railed against practitioners of a supposedly relativising ‘new theology’ that Pius feared would be corrosive of faith. Individuals were not named, but theologians who would become the formative intellectual influences on the Vatican II generation – such as the French Dominican Yves Congar and the French Jesuit Henri de Lubac – found it difficult to publish, or even to speak publicly, for the remainder of Pius’s pontificate.

Ventresca assembles the best ‘pro’ case that can be made, but Pius XII remains an unlikely candidate for the role of heroic moderniser, or indeed a hero of any kind. He was certainly a man who at a time of great moral challenge strove to do his best, for the church and for those who faced dehumanising imprisonment and death at the hands of a monstrous tyranny. The history of the Holocaust is testimony that his best was not good enough, and he is not the only European leader between 1933 and 1945 about whom that can be said. The question that should haunt his defenders, however, is not whether he could have deterred the Nazis by publicly denouncing their crimes; it is whether his silence actually emboldened them.

Comments powered by CComment