- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

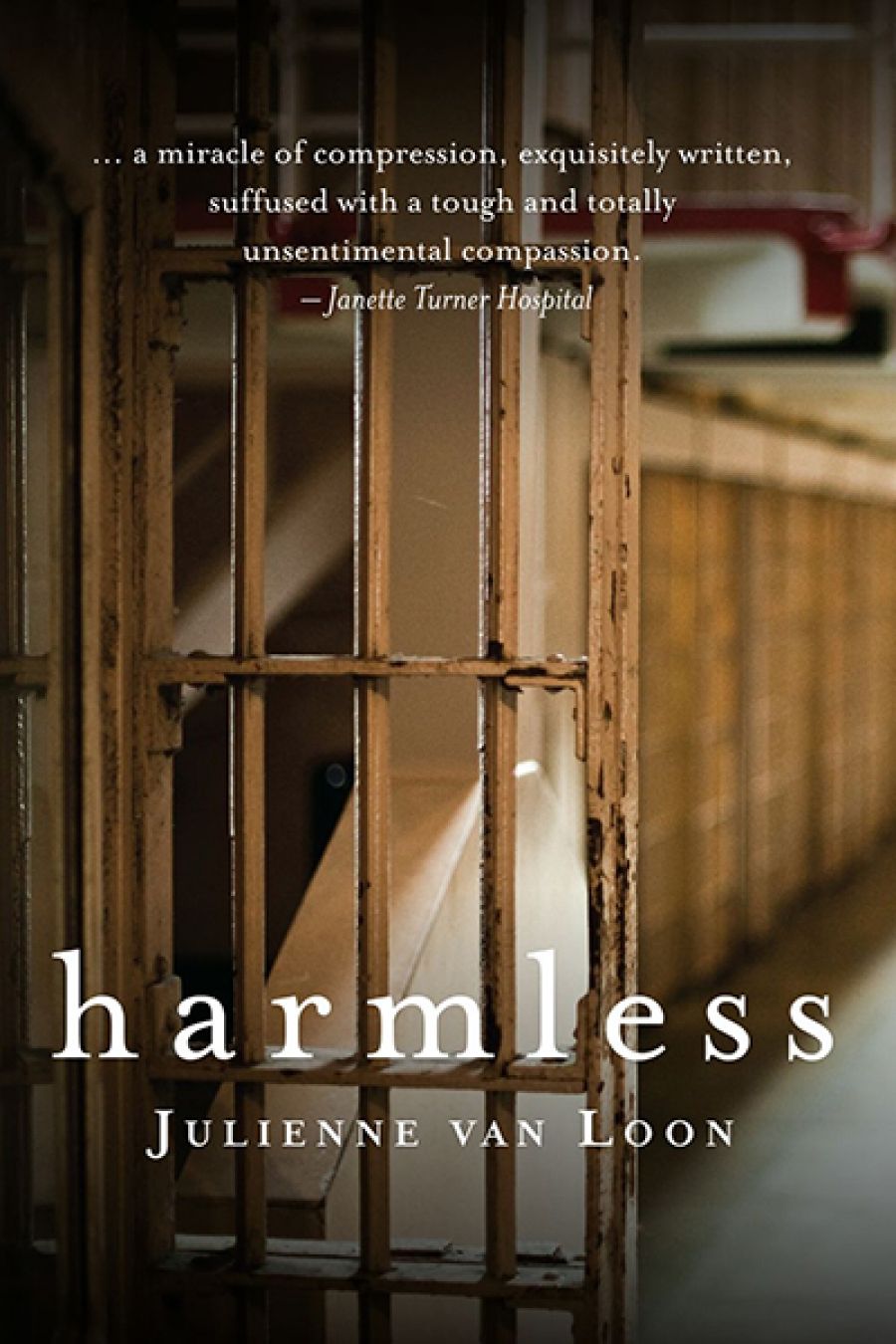

- Custom Article Title: Milly Main reviews 'Harmless' by Julienne van Loon

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Bonfire

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

A drunken woman stumbles into a party where people are gathered around a bonfire, determined to give the baby girl under her jacket to its father. When he refuses, she seizes the baby by the foot and throws it into the air above the fire. The child is Amanda and this is her start to a life that will be informed by criminals, harmed people – the crushed, flawed, abused. The image of Amanda as a baby – underweight, ‘wide-eyed’, suspended over the fire – effloresces and settles through this novella by Julienne van Loon.

- Book 1 Title: Harmless

- Book 1 Biblio: Fremantle Press, $22.99 pb, 137 pp

Amanda and an old Thai man, Rattuwat, make their way through bush and farmland, looking for the men’s prison east of Perth, where her father, Dave, is now incarcerated. Their vehicle has broken down and the two have become lost, then separated. Her father awaits the scheduled visit, but Amanda and the old man never arrive. He is sent back to his cell. As Amanda and Rattuwat wander separately, Dave, despairing and disintegrating, contemplates the events that led to his imprisonment.

Amanda has no guardian, and the state and its wretched child welfare system are closing in on the family. Her half-brother Ant cannot care for her; aged seventeen, he is running wild. The only person that could have cared for Amanda – Dave’s girlfriend, the noble, patient, and loving Sua – has died.

Harmless is partly told in the present; characters’ back-stories and the events that lead up to their circumstances are elucidated in reflective sequences. Van Loon, using an adumbration device familiar to her readers, lays clues as she goes; and at various points they go off like spray bombs, permeating the whole.

The taut narrative is excellently controlled, and part of the success of the short novel is that no detail is overindulged. Van Loon’s stories are set in a flat, salty, red, spinifexed Australia, the excessive depiction of which became tiring in Beneath the Bloodwood Tree (2008) and, to a lesser extent, in her Vogel-winning Road Story (2005). Van Loon’s capacity to render detail is exceptional. Brief and passing description – such as the girl’s dad stroking her hair back from her forehead at the funeral, or a gutter cutting someone’s fingers as they climb on to a roof – is evocative, eliciting a kind of sense memory in the reader.

The author draws on Buddhist literature – the Jātaka, tales of Buddha’s past lives in which he appears in different forms – as a king, a hare, a god – carrying the vast knowledge of his past existences. Old Rattuwat, Amanda’s companion, is come to Australia for his daughter’s funeral, here to oversee Sua’s transition into rebirth. He is aware of the strong connection that was between Amanda and his daughter. The girl’s interactions with the natural world are largely a way for us to experience her childish confusion and sorrow. Animate things take on a spiritual significance in Harmless, such as the family of orchids that she contemplates during a break from her long bush passage. She plucks them, an experiment to see the full lengths of the buried stems. But when she tries to put them back, it is futile. They will not grow – the stems only droop (‘I’ve killed them’).

At pivotal moments in a narrative and to great effect, Van Loon rises from the fictional plane and pans above it, describing a town at one moment or the lay of a narrative. It is a practised technique. What might be the literal interpretation of this – Rattuwat’s astral projection over a car park – is supposed to be phenomenal, but ends up being mawkish and slightly comical.

Amanda’s favourite animal is the turtle. She feels part reptile, and after the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, she is disturbed by the images of the poisoned gulf. The child’s voice, so credible, intelligent, and earnest, rarely lapses into contrivance. When her crisis peaks, Amanda goes through a kind of palliative transmigration: ‘Maybe she had always been the turtle, old, old, older than the old man Rattuwat. She swam between shards of light … She was Amanda Jane Loos, all, turtle, and she was living beneath the surface.’

One Jātaka tells the story of a tortoise dwelling in a pond. One day, two wild geese see the tortoise, and strike up an acquaintance with him. They say, come with us, friend, we have a lovely home far away from here. The geese promise to carry him, as long as he keeps his mouth shut and does not to say a word. They both take hold of a stick, and make the tortoise hold the middle with his teeth. Two children see this sight and exclaim, to which the tortoise replies, ‘What is it to you?’

Amanda, adrift without a parent and seeking an adult’s comfort, cries in the arms of her friend’s mother. Afterwards she realises that this was a mistake; Mrs Brown has had to inform the authorities about the situation, who now pursue her. But unlike the tortoise of the fable, Amanda will survive. As the wide-eyed baby is in mid-air, suspended above the fire, she looks down at her father – ‘I am yours’ – and he stands up and catches her. Someone will intercept Amanda, just as her father did that night.

Comments powered by CComment