- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The welcome in the title of this memoir refers both to Goldsworthy welcoming her baby son and to her recognition that her own life has irrevocably changed. The commonplace but also profound shifts resulting from motherhood are gently displayed for the reader, without sentimentality or the relentless self-deprecating irony of many motherhood memoirs and blogs. As readers of her earlier memoir, Piano Lessons (2009), will know, Goldsworthy’s touch is light but sure. It is a simple story of pregnancy, birth, family dramas, and learning to parent, but it is engaging and often very funny.

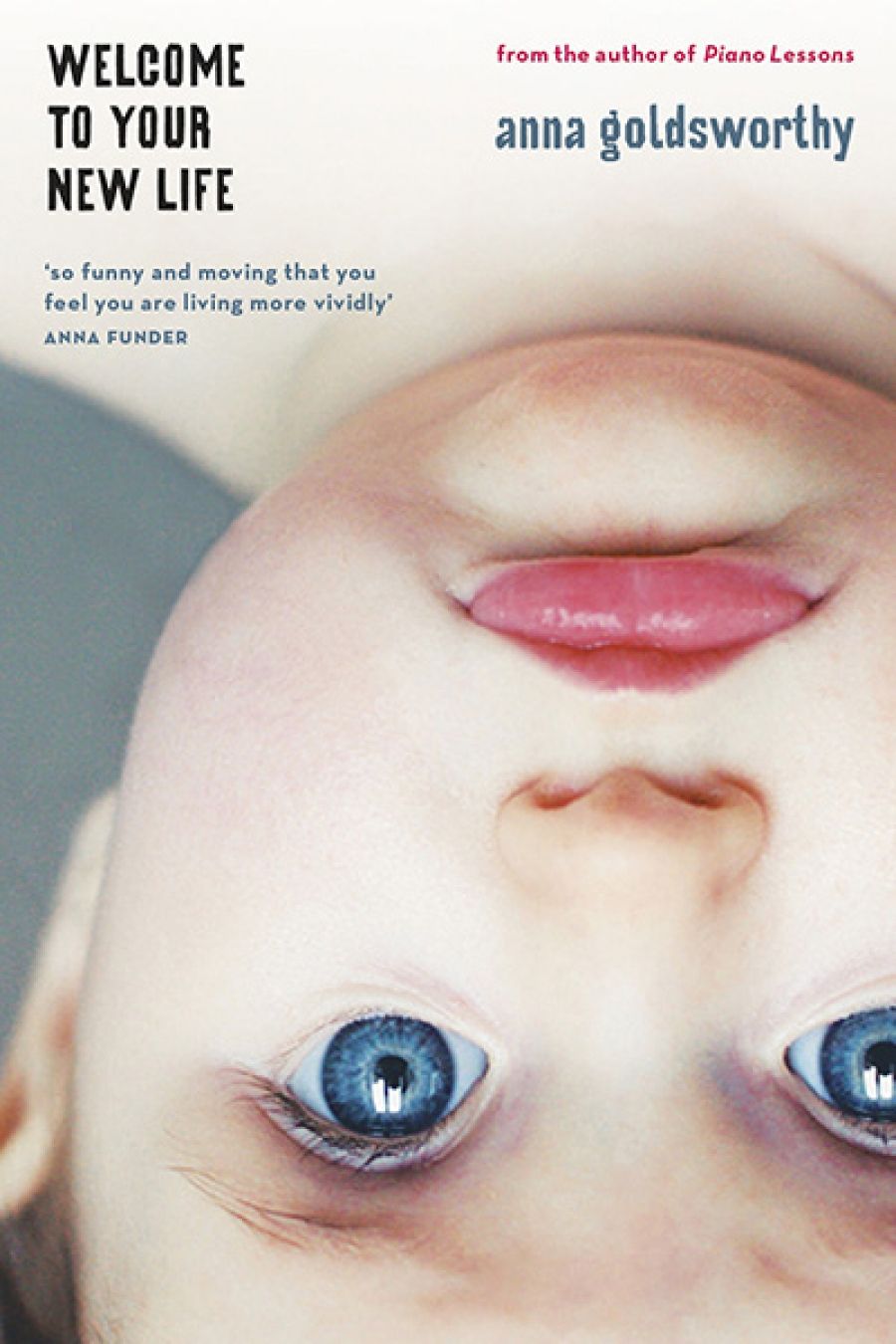

- Book 1 Title: Welcome to Your New Life

- Book 1 Biblio: Black Inc., $29.99 pb, 224 pp, 9781863955935

Some of the best scenes in this memoir describe the combination of romanticism about mothering and the high demands placed on mothers in contemporary Australia. Early in her pregnancy, friends tell Goldsworthy that she must avoid the medicalisation of childbirth and plan for her ‘birth experience’, complete with music, water, and aromatherapy. When she recoils from watching live births on YouTube, her friend suggests she may be in ‘labour denial’. Another friend assures her that labour pain is ‘a social construct’. Goldsworthy’s sister and parents are doctors and their responses to this are hilarious. Her sister, Sasha, says of the ‘birth experience’: ‘Here’s an idea! Have your experience when you’re not having a baby!’

The plethora of experts that surround new mothers, often treating them like infants, are depicted in a tone of wonder rather than judgement: the earnest lactation consultant with an invention made of plus-size underpants; the hypnotist who reads instructions from a textbook during a hypnosis attempt; the nurse facilitating a mother’s group teaching the women how to ‘have a conversation’. It is a relief to read common-sense advice from her parents and sister (‘If your body’s telling you to eat a sausage, then eat the damn sausage,’ says her father). It is also amusing to see her husband Nicholas ‘being stoical’. One of the pleasures of this memoir, in fact, is the sense of getting to know a whole family, not just Goldsworthy and Nicholas. The new baby is part of a warm and connected tribe, and the illness of the author’s brother and the death of her grandmother are woven into her experiences as a new mother, providing a poignant counterpoint. Particularly moving is the description of Goldsworthy’s mother struggling to manage her joy at the birth of her first grandchild and her anguish over the serious illness of her son in London.

Goldsworthy’s son is also a character in this narrative, although he doesn’t become interesting in his own right until he starts talking near the end of the book. Goldsworthy adopts the second person when speaking of her son: rather than using his name, she describes him as ‘you’, as though speaking to him. I found this slightly annoying, partly because the book doesn’t seem to be written for or to her son; it seemed to me to be a device rather than a necessary consequence of the narrative stance. That I found this only mildly irritating is testament to Goldsworthy’s skills as a writer; there is so much that works in this book. Her descriptions of the baby’s development in utero capture the awe that most of us feel about the creation of life.

The chapter entitled ‘Composting Toilet’ describes the overwhelming anxiety that motherhood can bring. Leaving the city in the heat of summer, Goldsworthy and her husband take their young baby to stay in a cottage by the sea. There, the composting toilet becomes a trigger for some extreme anxiety and the kind of detailed, madly logical craziness that this can entail. To write more would be to spoil the reading experience. Suffice to say that many mothers, and perhaps some fathers too, will recognise themselves, at least to some extent.

Recognisable to me, also, is the day when Goldsworthy leaves her baby son to travel to Sydney to promote her earlier book. ‘All of a sudden, I feel shy to find myself in the company of this other stranger: myself. What is it that adults do when alone?’ Moments like this are depicted but never laboured in this memoir. The back cover blurb likens the memoir to Rachel Cusk’s A Life’s Work (2001). This is somewhat misleading: Goldsworthy’s tone is much less abrasive than Cusk’s, and she is less scathing about the cheery childhood experts. She also has the ability to describe the joy and awe as well as the pain and confusion of early motherhood and to do so without the long commentaries that Cusk provides. Goldsworthy as mother is a more likeable person than Cusk – kinder to herself, less narcissistic, but also clear-eyed about her own failings. When she drops her son off at childcare for the first time she says to the carer, ‘His disingenuous expressions are always asymmetrical.’ This is a typical Goldsworthy touch: she doesn’t mock herself for saying such a grand sentence, or explain how it arises from that particular maternal combination of anxiety and love. Welcome to Your New Life leaves the reader to do the interpretation.

For me, the experience of mothering is a complex, ongoing encounter with the self as well as with another. Welcome to Your New Life is a funny and frank narrative about the early years of such an encounter. You don’t have to be a mother to enjoy this, just as you didn’t have to be a musician to enjoy Piano Lessons. It leaves me already wishing for Anna Goldsworthy’s next book.

Comments powered by CComment