- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Anthology

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

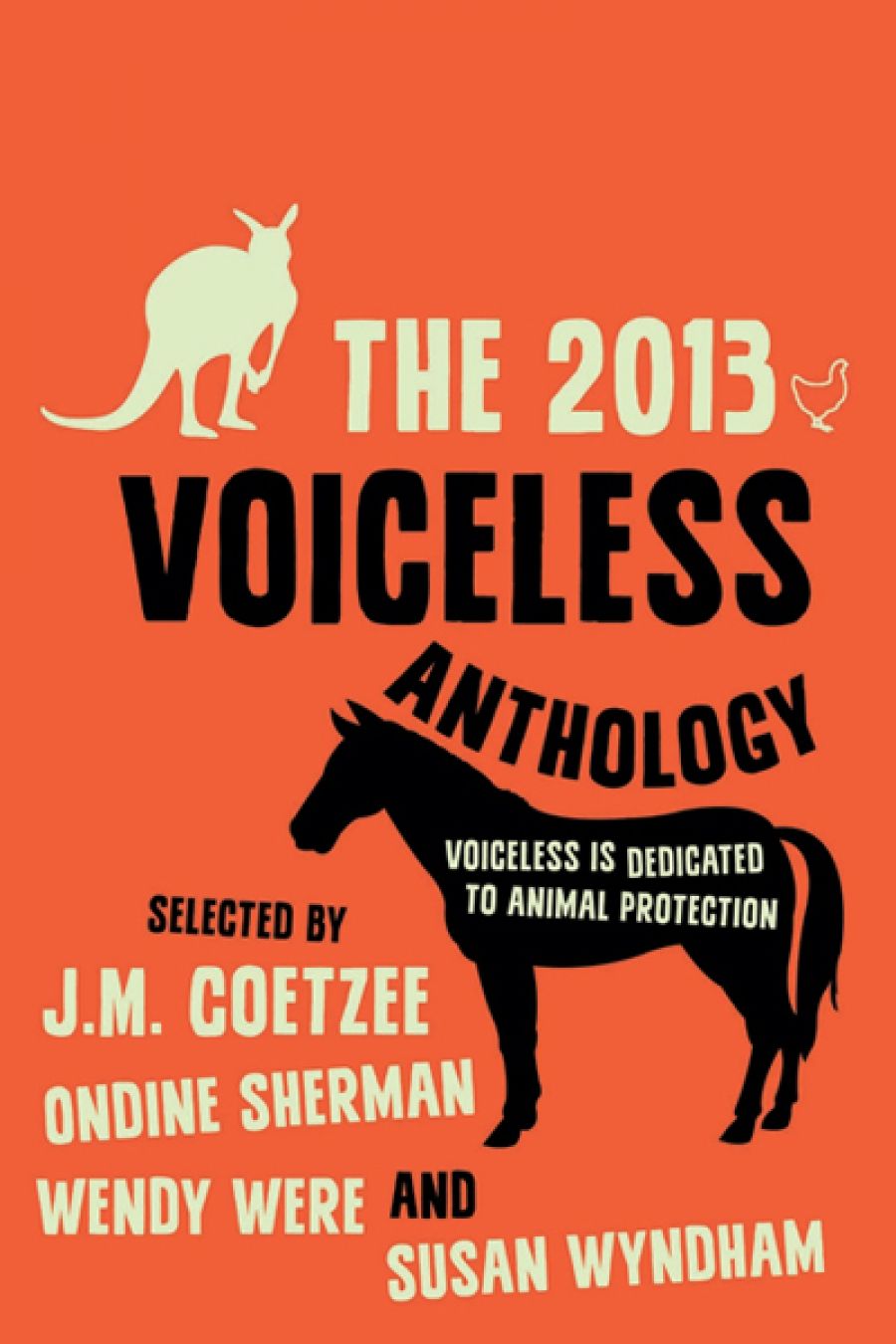

‘Death has a dual character,’ Zadie Smith writes in her novel The Autograph Man (2002); ‘it seems to be everywhere and nowhere at the same time’. Popular culture is currently awash with cookery programs and diet fads, yet the lives of animals, and the industries that deal in their deaths, have never been more absent from city life. It seems reasonable, therefore, that all ten stories shortlisted for the Voiceless Writing Prize – judged by J.M. Coetzee, Ondine Sherman, Wendy Were, and Susan Wyndham – animate the lives of animals in, or on the fringes of, rural Australia.

- Book 1 Title: The 2013 Voiceless Anthology

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $22.99 pb, 236 pp, 9781743313305

The 2013 Voiceless Anthology begins with Meera Atkinson’s essay ‘Confessions of a Vegetarian’, a rather artless via media between the ideals of veganism and the concessions one makes to the lifestyle, namely the occasional ‘to-die-for pair of patent leather boots’. While one can sympathise with the author’s equivocations on animals, accepting her passing comparison between the meat industry and the Holocaust (‘there is perhaps no more fitting human likeness to factory farming than the Nazi death camps’) is more difficult, especially given Atkinson’s laconicism on the topic. No defence of her hypocrisy, she concedes, ‘stands up against the knowing of my conscience’. The meat trade’s resemblance to Europe’s killing factories – the concealment, the order, the abstraction – recurs throughout the literature on animal rights, but we ought not to make the comparison so lightly.

The anthology’s overall emphasis is on mindfulness: a consideration of the environment and its sustainability. In ‘They Are Not Voiceless’, a Yolŋu family living in Bawaka in north-east Australia maunder through a tale of night-fishing for wäkuṉ, mullet. The story’s layered imagery and mythology evoke a connectedness with animals and country that is essential to Indigenous culture: ‘For us, animals are creative and vital, they have a knowledge and Law.’ To see oneself as distinct from animals, they explain, is to deny something fundamental about life itself and the sources from which it is sustained.

In his story ‘Caged’, Wayne Strudwick acknowledges the artificial origins of our viands: the tin sheds, tiered to the ceiling with inches-high cages and lit with banks of fluorescent lights. In this coming-of-age account, based on the time he spent at an agricultural boarding school, Strudwick recounts his instruction in the practice of debeaking chickens. ‘A tiny parcel of bones beneath the soft feathers, its feet pressed into his thumb,’ he writes. ‘And that tiny flurry of protest he felt in his palm, barely detectable, as he pushed the beak into the hot blade’. The anthology concentrates on these moments of considered observation, when children realise the sufferings that previous generations have invented for animals. A recurring theme in the book is that our relationship with animals has become so unnatural that many interactions with them have adopted a quality of the surreal.

‘The Other Days’, Olga Kotnowska’s story of a boy’s journeys with his father to harvest kangaroos, is coloured with the sense that violence against animals may indicate, or constitute, some minor category of violence within the family. Kotnowska writes of a sort of dream that recurs, sometimes sixty times a night, for the child: a kangaroo shot and hung from the ute, ‘and now, just before his father thrusts the knife’s point between the animal’s ribcage, when the eastern grey starts to spasm, Toby adapts to this, builds walls high and thick’. Kotnowska is concerned with the expectations of masculinity, particularly the emphasis on the primal duty to hunt rather than nurture – as the child learns to do with a joey whose mother has been killed.

Jessica Stanley’s ‘Not Long Now’ continues the theme of humankind’s responsibility to orphaned animals. As the protagonist convalesces from surgery on the Mornington Peninsula, she discovers a small grey joey ‘turning itself around inside the pouch of its dead mother’. The essential question is whether one has the right to blur the line between wildness and domestication, a line that academic Clare Palmer has argued is a morally relevant distinction in treating animals ethically. When we domesticate animals we create in them vulnerability, a reduced capacity to resist threats and understand environments, and we thus owe them greater moral consideration.

This concern may also extend to when we introduce fauna from abroad to these unfamiliar landscapes. Liana Joy Christensen’s story of the bilby, ‘Big Ears’, provides a reasoned introduction to these ethical issues of import and cohabitation. In her deeply felt essay ‘Fugue for Elsie’, Ann Coombs explores the plight of feral animals. For example: the practice of culling donkeys in the Kimberley, where jennies are fitted with tracking collars – known as ‘Judas collars’ – to lead hunters from one herd to another, whereupon all but the collared donkey are shot from the air. ‘After this happens a few times,’ Coombs writes, ‘the Judas jenny ceases looking for friends. She has worked it out: wherever she goes, the others die.’

As with any other’s existence, we can merely adumbrate the experience of animals; this anthology’s strength is to return focus to humans’ inner lives and the ways in which our troubled relationship with animals may be affecting them.

Comments powered by CComment