- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Subheading: His monumentality and gravitas

- Custom Article Title: Patrick McCaughey reviews 'Cézanne: A Life'

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

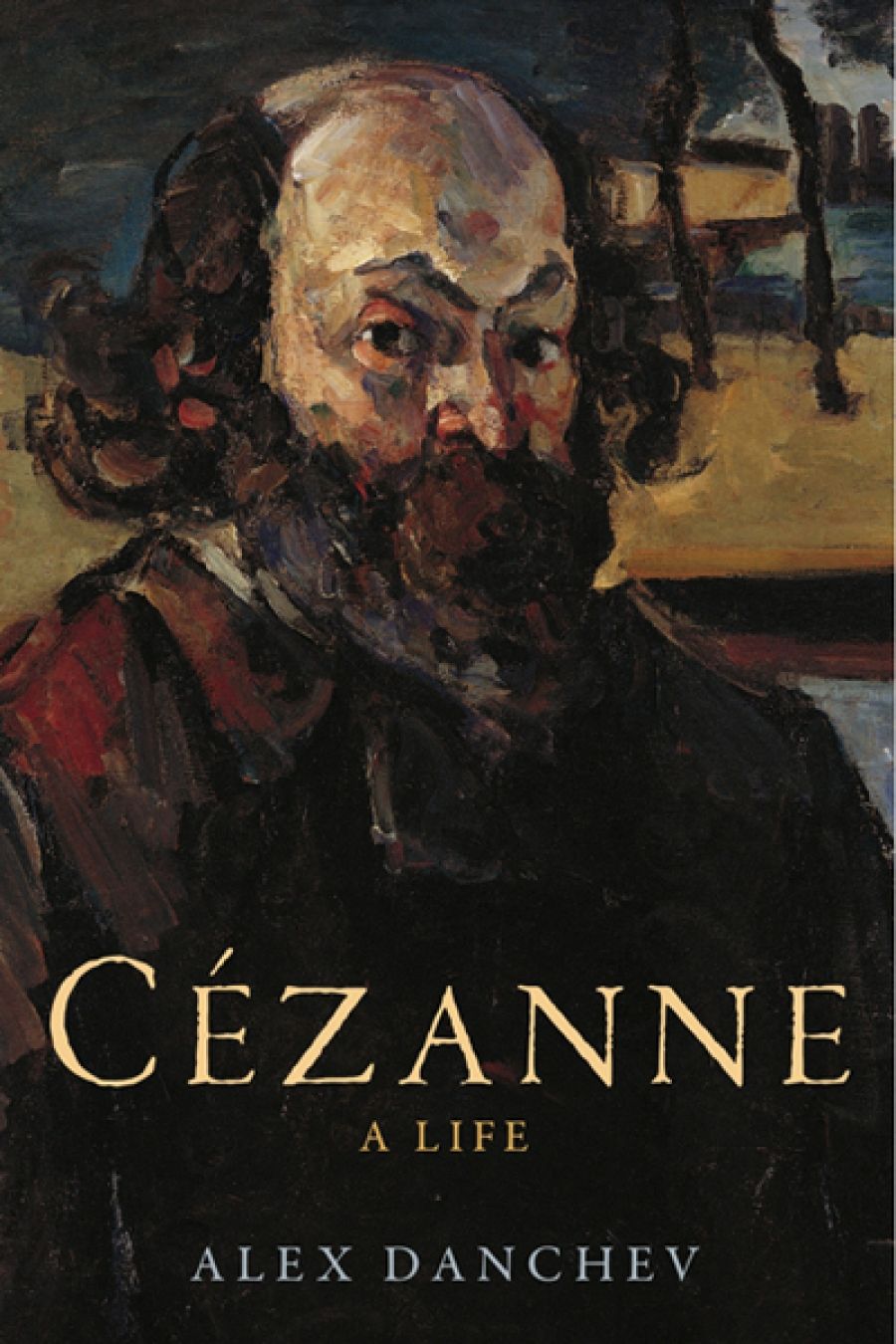

- Book 1 Title: Cézanne: A Life

- Book 1 Biblio: Profile Books (Allen & Unwin), $55 hb, 510 pp, 9781846681653

Alex Danchev might fairly hope that this serious, learned, and far-ranging life of Cézanne would give him admission to the high table of the club. Cézanne’s life is so extraordinary, its changes and chances mirrored so vividly in his art, that it deserves the close scrutiny and the skill with primary sources that Danchev brings to the task. But something falls short. What we have is a thoroughgoing study of the mind and the milieu of Cézanne. Only fitfully do we sense how the determination of the artist and the vicissitudes of life fashioned the art. Although the chapters follow a chronological sequence, Danchev’s book lacks the narrative drive of the best biographies where we are ineluctably drawn into an unfolding life. Danchev’s goal, maybe, is a loftier one: to emancipate Cézanne from the apocrypha surrounding the misanthropic genius of Aix-en-Provence and, through careful analysis of his relationship with his contemporaries, his family, and his times, to set forth a more raisonnable picture of the artist.

Still Life with Soup Tureen (1877). Once owned by Pissarro. Musée d’Orsay, Paris/Bridgeman Art Library

Still Life with Soup Tureen (1877). Once owned by Pissarro. Musée d’Orsay, Paris/Bridgeman Art Library

Cézanne’s relationship with Émile Zola, described by Danchev as ‘the main axis of his emotional life from cradle to grave’, threads its way through much of this long and dense text. They were boyhood friends in Aix, where Cézanne played the protector to the poor and bullied Zola. Although their later careers in Paris are asymmetrical – the novelist’s immense fame, the painter’s persistent obscurity – each remained a perverse ideal for the other. It was largely from Zola that the notion of Cézanne as ‘a great painter come to nothing’ sprang, taking final literary form in his roman à clef L’œuvre (1886). Danchev argues, against received opinion, that the publication of the novel was not the cause of their final estrangement, and observes that Manet, rather than Cézanne, was thought to be the model for the miserable artist, Lantier. Cézanne had been depicted in other novels of the day, and wrote Zola a polite note on receiving his copy. Instead, Danchev posits Zola’s ostentatious embourgeoisement at Médan, his country seat, as the real affront to Cézanne (‘A feudal looking building … standing in a cabbage patch’, Edmond de Goncourt bitchily called it, with its ten-metre long, nine-metre wide, and six-metre high study for the Master). Most fatefully of all, they were on opposite sides of the Dreyfus Affair.

Portrait of Paul Cezanne (1862–64)Cézanne had to wait until his mid-fifties for his first one-man show at Vollard’s in 1895. It was the turning point in his public reputation. Danchev reminds us that he was recognised and admired by his contemporaries early on. Manet was the first, followed by the warm embrace of the Impressionists. Cézanne would show in the first and third Impressionist exhibitions. Such affirmation meant much to the wayward Cézanne in his late twenties and thirties. Late in life, secure and successful, Cézanne would humbly call himself a ‘pupil of Pissarro’. After Zola, no relationship was more important artistically. Under Pissarro’s tutelage at Auvers-sur-Oise in 1872–73, Cézanne became Cézanne. The angry and tormented painter of the 1860s and early 1870s, the painter of violence, the manic, and the blackly melancholic, gave way to the painter bent on recording fully his sensations before the motif in all their mutating complexity, and on making an enduring art out of them.

Portrait of Paul Cezanne (1862–64)Cézanne had to wait until his mid-fifties for his first one-man show at Vollard’s in 1895. It was the turning point in his public reputation. Danchev reminds us that he was recognised and admired by his contemporaries early on. Manet was the first, followed by the warm embrace of the Impressionists. Cézanne would show in the first and third Impressionist exhibitions. Such affirmation meant much to the wayward Cézanne in his late twenties and thirties. Late in life, secure and successful, Cézanne would humbly call himself a ‘pupil of Pissarro’. After Zola, no relationship was more important artistically. Under Pissarro’s tutelage at Auvers-sur-Oise in 1872–73, Cézanne became Cézanne. The angry and tormented painter of the 1860s and early 1870s, the painter of violence, the manic, and the blackly melancholic, gave way to the painter bent on recording fully his sensations before the motif in all their mutating complexity, and on making an enduring art out of them.

Danchev gives a sympathetic portrait of Pissarro, the benign anarchist, but muffles the great turn in Cézanne’s art. He interprets the dark visions of early Cézanne as the product of his reading, fashioning his identity from models found in Stendhal, Balzac, and Flaubert. ‘Quick impulses, decisive actions betray the choleric man. Awkward movements, decisions full of hesitations and reservations reveal the melancholic’ (Stendhal). The early Cézanne of the slashed, palette-knifed portraits and the gloomy landscapes marks an artist of potency and force, turned in upon himself with no alternative direction in sight. There is a touch of madness in these driven works. Pissarro and the lens of the Auvers landscape saved Cézanne from his ‘chaotic self’, as Peter Gay called it. The dread, the anxiety, behind those dark visions, so exactly described by Picasso as Cézanne’s inquietude, never entirely left him. We sense the latent psychic energy in the quivering stroke of the mature works, the patches of paint, laid side by side, in contrasting colour that both model a form and animate a surface, perpetually agitated.

One would like to have heard more from Danchev on the great Bathers and their fleet of studies that haunted Cézanne’s final decade and rather less about the photograph of the aged Cézanne sitting in front of the Barnes version. Zola may have got them right in L’œuvre when he said that they represent ‘… his chaste passion for the flesh of a woman, a foolish love of nudity desired and never possessed, an impotence of satisfying himself, to create this flesh so much that he dreamed of holding it in his two bewildered arms. These women whom he drove away from his atelier, he adored in his paintings – there he caressed them and violated them, desperate that through his tears he would not have the power to make them as beautiful and vibrant as he desired.’ (Surprisingly, Danchev does not quote this.) In Bathers, the climax of his journey, Cézanne can quench and relieve his inquietude even as the nudes surge, stretch, or squat. To call them ‘dreamscapes’ is something of a cop-out, unworthy of such a thoughtful text.

Paul Alexis reading to Émile Zola (1869–70)

Paul Alexis reading to Émile Zola (1869–70)

Throughout this long book, Danchev pays recurring attention to the Cézannian effect, the Cézannian moment. He enlists an imaginative variety of voices from contemporaries such as Renoir (‘he can’t put two strokes of colour on a canvas without it already being very good’) to the poets from Rilke, primus inter pares,to Allen Ginsberg via Derek Walcott, Seamus Heaney, Charles Tomlinson, and e.e. cummings. Rilke is the most intense reader of Cézanne, equal to T.J. Clark in his sustained scrutiny of the work. After a minute-by-minute account of Madame Cézanne in a Red Armchair (1877), plotting the succession of ‘green yellows’ and ‘yellow greens’, Rilke exclaims ‘It’s as if every part were aware of all the others’, precisely conveying the sense of absolute unity and completeness in Cézanne even when he leaves off the canvas early.

Danchev has less time for the art historians. Both John Rewald and Meyer Schapiro, éminences grises of Cézanne studies, come in for sharp reproofs, not altogether fairly. Whatever disappointment Danchev’s Cézanne may be as biography, there remains much of interest in the range of sources he deploys to locate the mind of Cézanne in the work.

Paradox abounds in Cézanne and is the mainspring of the ever-renewing inspiration of the work. The artist who struggled to realise in paint his sensations of light, the changing faces of the landscape, the apples, and compotiers of the still lifes was equally the master of the inner life of his subjects. The Card Players – particularly the large version in the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia (1890–92) – is his masterpiece in this vein. The players are rapt in the contemplation of their cards; the bystanders dare not move lest it break their concentration. Together they form a circle of inwardness. The monumentality and gravitas that Cézanne imparts to these farm labourers, odd job men, gardeners, are immense and moving. Nothing in nature, nothing human, was alien to him.

Comments powered by CComment